Kalliopi Minioudaki

Nirbhaya(s)’s Double Lament in Unforgetting and Protest

by Kalliopi Minioudaki

in Monika Weiss-Nirbhaya, Centre of Polish Sculpture in Orońsko, 2021, pp. 85 - 107

Lament is the sound and silence of trauma.

Monika Weiss [1]

Grievability is a presupposition for the life that matters.

Judith Butler [2]

Jyoti Singh died in a hospital room in Singapore. Her body was irreparably turned inside out thirteen days earlier, on 16 December 2012, while she was brutally raped and tortured for two hours by six men on a bus that continued to move through the streets of Delhi, a city whose body has been itself repeatedly violated over the centuries by colonizing and westernizing forces. She was returning home after an evening to the movies with a male friend. She was twenty-three years old.

Unlike the countless losses from rape and sexual violence whose memory is written out of the archives of collective trauma and its public staging, Jyoti Singh is not forgotten. She has been mourned and celebrated as “the fearless one,” “Nirbhaya” in Hindi. Veiling the identity of the rape victim in compliance with Indian law, “Nirbhaya” transformed her memory into a symbol of defiance of the threat of public space for women, making her an involuntary heroine that empowered women’s recent struggles against sexual violence in India and around the world.

In their dedication to Jyoti Singh as Nirbhaya, Monika Weiss’s eponymous yet-to-be-realized sister monuments work to undo both female victimhood and the masculinist heroics of public art, honoring the sacrifice of all women who have endured torture and rape. They radically yet poetically counter-memorialize rape in the public space. Their titular dedication echoes the ethical considerations catalyzing the “political force” [3] of the multimedia audiovisual poetics of lamentation that marks the artist’s exploration of traumas she has neither directly witnessed nor experienced. Like the transformational hiding and showing enacted in the unnaming of Jyoti Singh, Weiss protectively veils a body of trauma to unveil rape, defying the re-traumatization of direct re-presentation while also refusing to surrender the role of beauty in political art and its contribution to struggles for social change and justice. [4]

Her work’s response to violence and its archive dialogues with the poetic criticality and problematizing of the representability of suffering by artists as different as Alfredo Jarr and Doris Salcedo, while repowering, through its performative experimentation, the space given to art between social practice and activism for the responsible and “response-able”[5] remaking of the cosmopolis, from an intersectional feminist perspective.

While layering the complexity of women artists’ prolific but disparate — as revealed in recent feminist art historical studies — exploration and castigation of the most “unheroic” and “unspeakable” trauma that unites women’s individual and collective experiences of gender-based violence; and has globally reunited women to speak of and combat all its manifestations, women’s rape is only a part of Weiss’s condemnation of violence with Nirbhaya. [6] Keeping her alive by “putting her to sleep” (koiman in ancient Greek) within an anti-triumphal, human-sized, and womb-like (in its fluid interior) vessel, Weiss frames her mourning of Jyoti Singh’s murder with a mournful condemnation of colonization, shaping the periphery of her open tomb by placing down replicas of India’s chief colonial war monument, — the All India Gate Memorial — a foundational monument of New Delhi inspired by the Arc de Triomphe. In this act, Weiss symbolically topples the erectile glorification of war memorials, both of the British and French empires, to reveal the colonial violence they attempt to hide, and to lament the ungrieved bodies buried in the distortive foundations of national master narratives of history in public space.

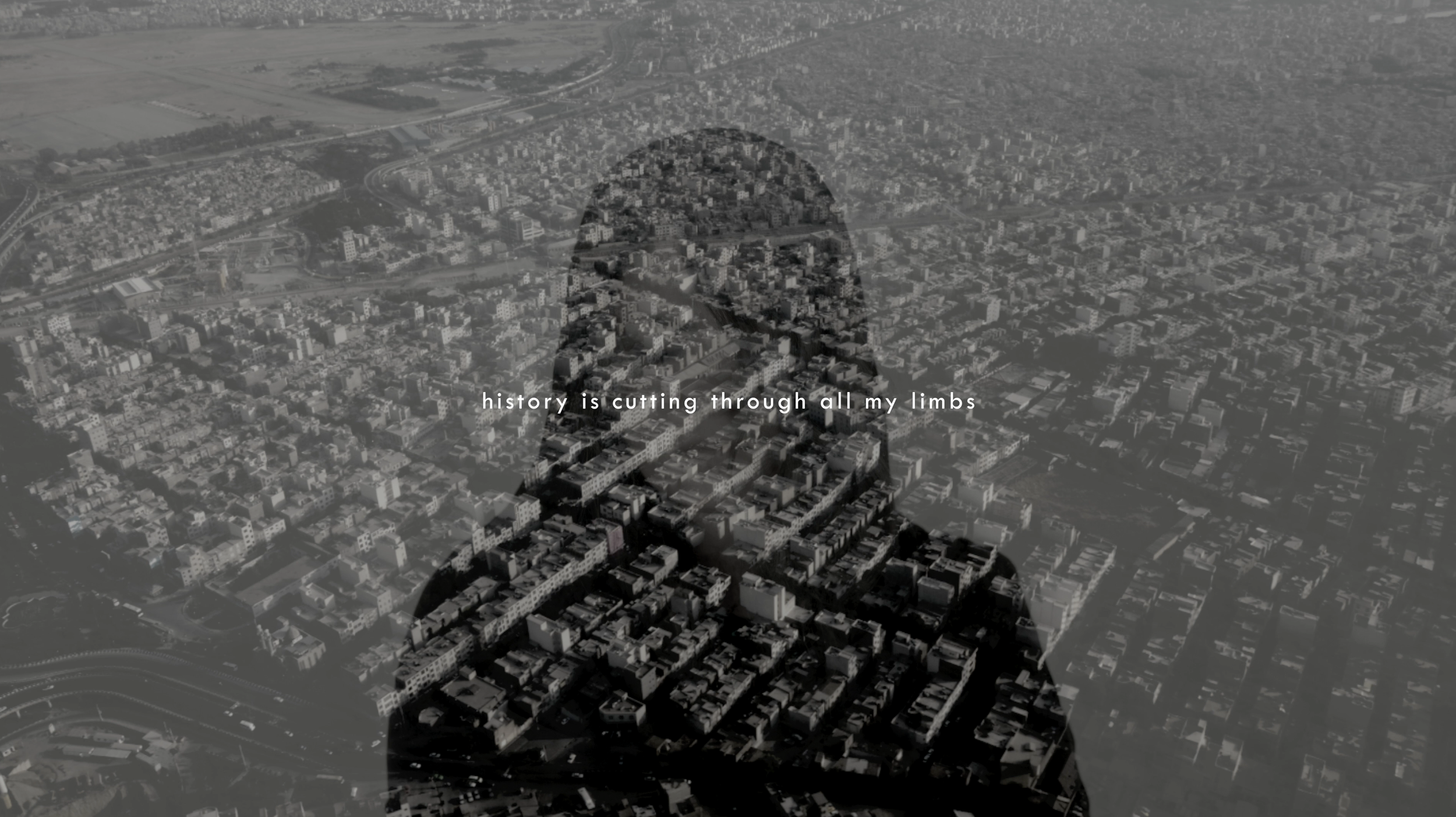

Culminating the audiovisual explorations of Jyoti Singh’s and India’s rape, begun in 2015 in the film and sound compositions of Two Laments (19 Cantos), Weiss continues to contemplate the fraught relation of women and cities as embodied sites of trauma variously manifested throughout her work. [7] As a warning “memento,” [8] this twin anti-monument to a brutally punished flâneuse, speaks of rape as trauma and crime, unburying the amnesia servicing the patriarchive of history and its narration in the public space across the geo-cultural borders of many cities and countries. [9]

Nirbhaya’s wounded body is neither buried nor re-presented in Weiss’s Nirbhaya. It is lamented through the silence, near stillness and repetitive ritual gestures of its performative enactment by a chorus of women of different origins and intersectional identifications in her studio, including by the artist herself. Shrouded by black cloth and sensuous moves, it will be cradled in her stone cenotaph through its specter’s projection on its water deathbed. Birthed through light, this changing specter morphs Nirbhaya into the multiple known and unknown violated bodies of history, myth and art that it evokes, including that of nature. The product of Weiss’s signature digital editing of her filmed performances, this symbolic metamorphosis regenerates the supine body through its doubling and its melding with that of others—including the bodies of the viewers and the park, reflected on the water. With its representation falling apart and coming together as an “other” or water, trauma is both evaded and amplified, suspended through time; to be inhabited in time and in silence by the visitor.

At the heart of this ambiguous metamorphosis, which differs from Weiss’s lament of Jyoti Singh’s rape in Two Laments (19 Cantos) in its focus on doubled but solitary, and at times confrontational, ritual enactments of her disemboweled body by one performer, Nirbhaya’s spectral stand-in turns into a tree. This in part site-specific transformation evokes the water nymph Daphne in her desperate escape from Apollo’s pursuit and rape. Revisiting Daphne’s myth, Weiss begins to unravel the sexualizing spectacle of yet another foundational rape myth of Western literary and visual culture while staging the brutality of rape and the hardship of its survival, perhaps with a nod to Ovid’s own acknowledgment of women’s experience of trauma in the light of Daphne’s silencing metamorphosis.

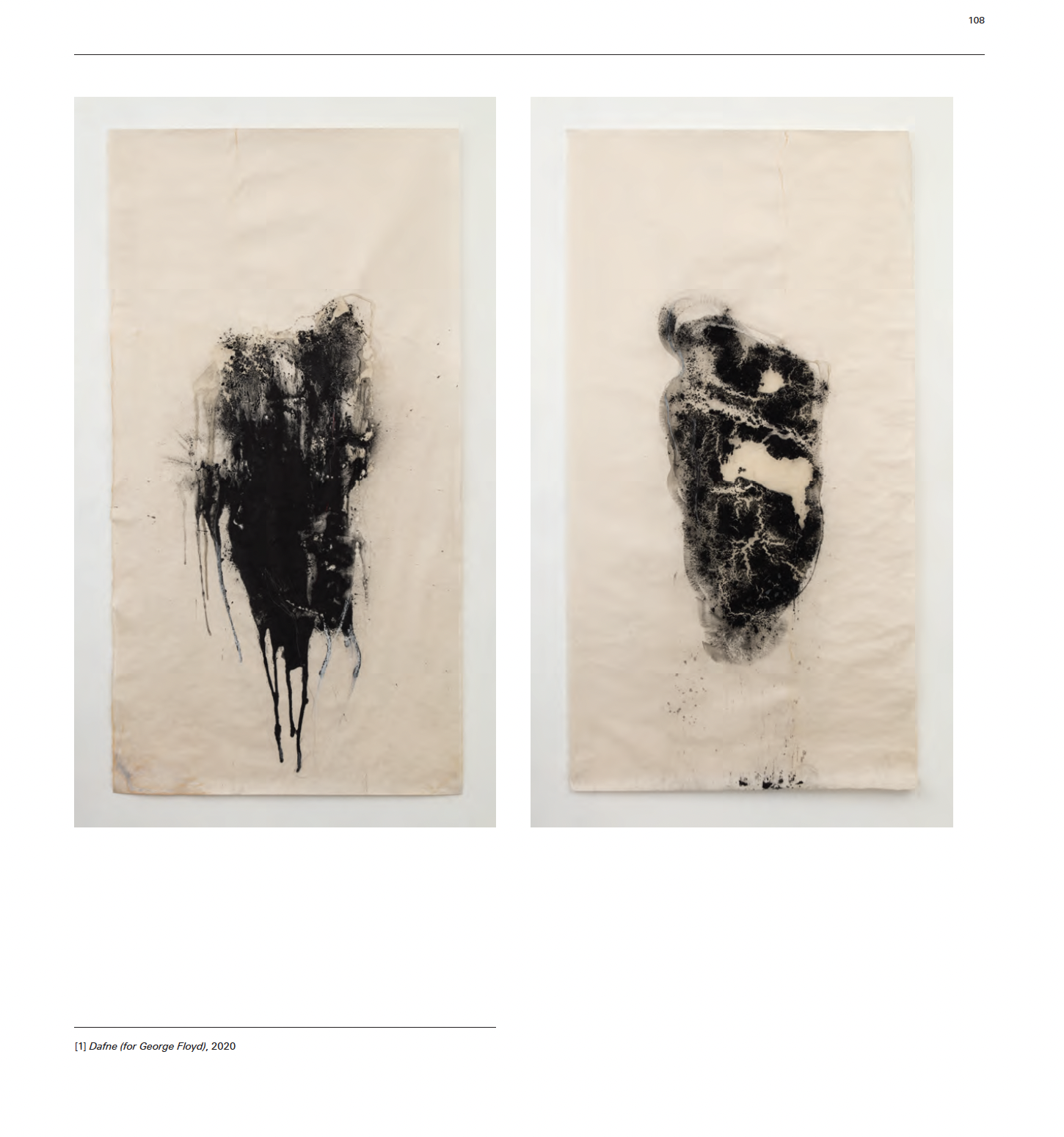

The traumatizing effect of a body becoming a tree is captured by the hardening of materials into stony yet fragile black matter in the drawing suite that Weiss dedicates to Daphne in the context of this work.[10] Conversely, the liberating underpinnings of Nirbhaya’s metamorphosis into nature converse with the eco-feminist spirituality of the feminist ancestors of Weiss’s performative practice, the most evident for this work being Ana Mendieta. [11]

Nirbhaya will also be sonically mourned from afar, at least in the monument’s permanent iteration for the Centre of Polish Sculpture in Orońsko, with a doubling of the silent lament of her ritual self-caress transpiring in the sculpture by Weiss’s series of sound compositions for Nirbhaya titled Metamorphosis (still in progress). The latter will be transmitted from a sound station located at a different place in the park. Spatializing the dialectic of archaic lament, meant as a dialogue between the lamenter and the departed in the artist’s understanding of lament, itself informed also by her training as a musician, this splitting of the visual (silent) and sonic (choral in effect) aspects of the work charts the affective itinerary of one’s pilgrimage to Nirbhaya through the park, rendering the viewer the protagonist in Nirbhaya’s ternary structure of lamentation and the absence it surfaces through image, sound, and silence. Such an itinerary commemorates the prolonged violation of Jyoti Singh’s body through space while orchestrating the silent and sonic components of the monument’s lament, in the appositely “post-lingual” [12] breakdown of image and sound that characterizes Weiss’s film editing and the digital processing of her piano improvisations of Nirbhaya.

With the koimesis[13] of Nirbhaya as an offering that tenderly mourns and wrathfully condemns rape and war, sexual and colonial violence, revealing the intersectionality of violence and the coloniality of power, along with the cultural amnesia that condones them, Weiss continues to propose lament as a potent gendered means of “unforgetting”[14] and protest. She radically revises traditional public memory art, namely the monument and the memorial, activating audiovisual temporal sites of transcultural and transhistorical grief that, unmoored from their site-specificity, can resonate everywhere. Weiss’s Nirbhayas not only honor marginalized stories of the oppressed in the public space, but through her poetics of lamentation, they both sonically and performatively “repollute” [15] that space with the emotive power of grief that makes possible a relational awakening to the archive’s omissions and the embodied remembering that can ward off the repetition of the horrors of power and history that they expose by nurturing resistance.

Ritual lamentation, deemed illegal at the very inception of Athenian democracy in favor of a rational praising of the heroic war deaths that sustained it, has been an empowering and participatory domain of female embodied expression — whether seen as an undermined genre of women’s culture or as a patriarchal displacement of women’s “dangerous” voices from public space.[16] As various studies argue in light of the content and antiphonal structure of ancient laments and their ritual performance reflected in tragic poetry and, until recently, in group lamentation practices in rural areas of Greece, since antiquity lamentation’s function exceeded that of the expression of individual pain or anger, remembering and honoring the dead, and securing the “goodness” of a death. Whether in ancient tragedy’s kommos or in modern moirologia, lamentation often performed a marginalized yet dissident sociopolitical “truth telling” targeting war and patriarchal oppression, while enabling a social bond among lamenters that fostered solidarity, a “sisterhood in pain”. [17]

It is the gendered thematics and performative language of Weiss’s work, in all the conceptual and aesthetic intricacies of her multimedia practice and the subtleties of her subversion of (male) art’s and art history’s silencing or heroizing of rape, that appealed to me when I first experienced it in a studio presentation by Monika Fabijanska, for which I am deeply grateful. [18] But it is for the potential of the collective grief, as activated by Weiss’s work, to unite, irrespectively of gender, the oppressed in protest and to restore an inclusive polis, that I have turned and returned to as curator to comment on the biases and ungrievable lives marking the financial and refugee crises in Greece. [19]

It is no coincidence that while in New York, experiencing the darkest days of the first upsurge of the Covid-19 pandemic in the US, the ritual gestures of lament in Weiss’s performative poetics and the whispers of her black-clad protagonists haunted me as the insistence of a much needed intervention. The post-lingual expression of grief of her multimedia and audiovisual enactment of lamentation, as in Wrath and Two Laments (19 Cantos) but also older works like Sustenazo (Lament II), could speak of and to despair in the face of incalculable loss, while still relevantly addressing the acceleration of gender violence during quarantine. Especially as the pandemic redrew the lines between public and private spheres of gender-based violence and confronted New Yorkers with the intersectionality of the crisis through the displacement of bodies deemed ungrievable, both living and dead, to the margins of the triumphally rising center of the city. It is not hard to imagine that in Nirbhaya’s first iteration — while a rare counter-monument to rape, the first in Poland — the globality of its lament will be reinforced by the pandemic’s ‘brutal lesson … in the inescapable universalism of a trembling fragility and vulnerability to suffering,” [20] amplifying the entanglement of individual and the collective deaths; and the interconnectedness of all forms of life enabling Nirbhaya’s metamorphosis.

It is the current transatlantic chorus of protest for the lives that continue to not equally “matter” — whether those of African Americans in the US or women in Poland — joined by cries of the multiple wrongfully unprivileged, unprotected, feared, hated, persecuted, silenced or murdered “others” in both countries, that re-contextualizes the critical targets comprising Weiss’s intersectional focus on violence and its forgetting, in a relentless updating of the global timeliness for her double lament. Given that the origins of Nirbhaya long precede this turbulent moment, its sister vision culminates a critique of selective remembering — the systemic forgetting — that sustains the ongoing sexism and racism in their postcolonial imbrication, in all its differences, around the world. Rather than directly addressing them, Nirbhayas have anticipated the accumulated urgencies foregrounded by the global #MeToo movement or the rekindled #BlackLivesMatter movement, and the multiple biases, inequities and unfreedoms plaguing citizenship in the Polish and US society today.

The critique of public art’s role in perpetuating the misogynist and racist nationalist ideologies that such movements have precipitated, especially in light of the most recent attacks on memorial and monument art in the US and Europe, has been long presaged, after all, by her art’s memory work and public interventions in both countries.[21] As argued by Vanessa Gravenor, ‘Weiss is deeply committed to the reconciliation of historical, profoundly imbedded memory with contemporary occurrences that signal repetitions, and horrific returns of the same.’ [22]

Neither as an American nor as a Polish artist, but as a “postmigratory” world “denizen” [23] that traverses both, Weiss brings home Nirbhaya to Poland and the US, her two broken homes across the Atlantic, from India, with a wrathful condemnation of the wounds their states inflict, or allow being inflicted, on their own people as well as others, in a mode of gendered “truth telling” whose lament of the state of human rights in the patriarchal and white supremacist democracies of global capital has become more timely than ever, both for the intersectionality of oppression and the “differentiated universalism” [24] of the unassimilable challenges confronting women around the world.

Hers is a gesture of cosmopolitan feminist care for the suffering bodies of the others in us that may allow Nirbhayas to engender a critical public sphere of belonging with others “that enables transversal dialogues across difference.”[25] But it transpires with her practice’s embodied social engagement: Weiss’s life-long wrathfully tender lament of the female body’s abuse in life and art which she both watchfully and protectively continues to try to “put to sleep” at a moment of change that has not yet come. [26]

Kalliopi Minioudaki, New York and Athens, 2020

Notes:

[1] Monika Weiss, ‘Nirbhaya: Triumphal Gate Lying Down – Memory, Amnesia, Flatness, Wrath. Notes Towards a Project,’ Sculpture Today 4: Anti-Monument: Non-Traditional Forms of Commemoration, Eulalia Domanowska and Marta Smolińska, eds, Orońsko: Centre of Polish Sculpture, 2020.

[2] Judith Butler, Frames of War: When is Life Grievable?, New York: Verso, 2009.

[3] ‘Group mourning is an act of political force, and not a reaction to individual grief.’ Monika Weiss, ‘Conversation with Julia P. Herzberg,’ in Sustenazo (Lament II), Santiago, Chile: Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos, 2012, p. 30.

[4] Eventually, Nirbhayas effectively yet poetically would preserve also the name of Jyoti Singh, in keeping alive the memory of her rape murder, echoing the chanting of the names of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor marking the memorial acts of the BLM protests that frame the writing of this short reflection. For the critique of Jyoti Singh’s unnaming by her parents see https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/feb/16/jyoti-singh-parents-call-for-honorary-museum-nirbhaya-to-use-her-real-name. The oscillation of my references to her both by her posthumous and real name, is meant to honor both the politics of naming and the intention and ethics of the artist in this symbolic response to Jyoti Singh’s tragic fate.

[5] As understood by Marsha Meskimmon, who, in defining the ethical and political responsibilities of be(long)ing at home everywhere, illuminates the aesthetics of cosmopolitanism, positing that ‘cosmopolitanism asks how we might connect, through dialogue rather than monologue, our response-ability to our responsibilities within a world community,’ in Contemporary Art and the Cosmopolitan Imagination, London and New York: Routledge, 2011, p. 7. See also ‘From the cosmos to the polis: on denizens, art and postmigration worldmaking,’ Journal of Aesthetics and Culture, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2017, pp. 25–35.

[6] The upsurge of feminist interest in the US in the rather understudied and difficult topic of rape in the work of women-identifying artists was cast through different lenses by the groundbreaking exhibition of Monika Fabijanska, The Un-Heroic Act: Representations of Rape in Contemporary Women’s Art in the U.S., New York: Anya and Andrew Shiva Gallery, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York, 2018, and the studies of Nancy Princenthal, Unspeakable Acts: Women, Art and Sexual Violence in the 1970s, New York: Thames & Hudson, 2019, and Vivien Green Fryd, Against Our Will: Sexual Trauma in American Art since 1970, Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 2019.

[7] For the intertwining of the violated bodies of women and cities, including the physical space of the cities in which they are presented, see Vanessa Gravenor’s in depth study of Two Laments (19 Cantos) and earlier works from the Shroud Series, such as Wrath, and the unrealized performance Shrouds II (Tahir Square), in ‘Monika Weiss’s Two Laments,’ n.paradoxa – international feminist art journal, Vol. 37, 2016, pp. 83–88.

[8] Julian Bonder, ‘On Memory, Trauma, Public Space, Monuments and Memorials,’ Places: Forum of Design for the Public Realm, Vol. 21, No 1, 2009. Last accessed at https://placesjournal.org/assets/legacy/pdfs/on-memory-trauma-public-space-monuments-and-memorials.pdf

[9] On the flâneuse in Weiss’ work see also Weiss 2020, pp. 405–406.

[10] In turning to Daphne, sans Apollo, a Greco Roman rape myth widely depicted in Western art since antiquity and a staple of garden and public sculpture, Weiss not only dialogues with the feminist retelling of male fantasies, but combines Nirbhaya’s critique of monument/memorial art’s erasure of the female (wounded) body, with a critique of its objectification by public statues, in a double targeting of the misogynism of centuries of (public) art, not yet eclipsed from public space.

[11] Mendieta is here evoked more for the melding of the female/goddess body with nature in her siluetas and the legacy of the 1970s feminist body art on Weiss’ performative practice and take on the female body, rather than her provocative thematizing of women’s rape and murder. Daphne, conversely, has been figuratively reclaimed as an earth goddess by Audrey Flack, in Colossal Daphne Head, 2008, now at the North Dakota University Campus. I would like to reserve a comparative discussion of the dialogue of Weiss’s approach to women’s rape and trauma with her second wave feminist predecessors and contemporary women artists for another essay. I am however compelled to point out that while her black-clad chorus of lamenters embodying the empathetic expression of grief that her work performatively enacts is not limited to Weiss’s works that address specifically rape — in fact they predate Nirbhaya in works that cut across the abjected memories and traumas of the Holocaust and World War II, Weiss’s Nirbhayas inevitably pay homage to Suzanne Lacy’s and Leslie Labowitz’s groundbreaking performative yet temporary counter-memorial In Mourning and In Rage of 1977, as well as to the legacy of second-wave feminist practice on the art and activism today around this difficult topic.

[12] For the “post-lingual” expression of grief in lament informing the de-composition of her video and sound editing see Weiss 2020, p. 400.

[13] The noun koimesis etymologically derives from the ancient Greek verb koiman (to put to sleep) that Weiss performatively enacts herself and uses as the title of early performances. It is used here for the iconographic evocation of the Dormition of the Mother Mary, in its double signification of Mother Mary’s death and resurrection as it resonates the placement and silhouette of the palimpsest of bodies in Nirbhaya. As a title, it returns in Weiss’s Koiman II – Years Without Summers (24 Nocturnes): a series of works in progress comprising 24 film projections, 24 sound compositions, and 24 large-scale charcoal and graphite drawings, dedicated to her late mother, pianist Gabriela Weiss who passed away in April 2017, and to all ‘currently displaced refugees and migrants trying to find shelter.’

[14] “Unforgetting” is a Weiss neologism that astutely captures the goal of her memory work. I am profoundly grateful for the many conversations with the artist throughout the years that have fueled my understanding of her work as reflected in this essay.

[15] Monika Weiss, in ‘Two Laments’. Monika Weiss & Meena Alexander in Conversation. Moderated by Buzz Spector.

[16] See Anne Carson, ‘The Gender of Sound,’ in Glass, Irony and God, New York: New Directions, 1995 and Gail Holst-‐Warhaft, Dangerous Voices: Women’s Lament and Greek Literature, Padstow: T J Press Ltd., 1995. See also the classic study of Margaret Alexiou, The Ritual Lament in Greek Tradition, Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002.

[17] See Andrea Fishman, ‘Thrênoi to Moirológia: Female Voices of Solitude, Resistance, and Solidarity,’ Oral Tradition, Vol. 23, No. 2, October 2008, pp. 267–295, for the role of lamentation in creating solidarity, or sisterhood of pain as defined in light of modern Greek women’s lamentation practices by Anna Caraveli-Chaves, in ‘Bridge between Worlds: The Greek Women's Lament as Communicative Event,’ The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 93, No. 368, April–June, 1980, pp. 129–157. See also Durdina Šijaković, Shaping the Pain: Ancient Greek Lament and its Therapeutic Aspect, Belgrade: Belgrade Institute of Ethnography, 2011, and C. Nadia Seremetakis, ‘The Ethics of Antiphony: The Social Construction of Pain, Gender, and Power in the Southern Peloponnese,’ Ethos, Vol. 18, No. 4, December 1990, pp. 481–511.

[18] I am also deeply grateful to my dear friend and colleague Allison Unruh, Associate Curator from 2015 to 2019 at the Mildred Lane Kemper Museum, Washington University in Saint Louis, where Monika Weiss teaches, for this encounter that led to the outdoor projection of Wrath (Canto 1, Canto 2, Canto 3) on the walls of the newly found Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center housing the National Opera and Library in Athens in 2015, cocurated by the author, Barbara London and Francesca Pietropaolo with artistic director Robert Storr.

[19] Rather than privatizing, ‘grief exposes us to the constitutive sociality of the self, a basis for thinking a political community of a complex order,’ according to Judith Butler, ‘Beside Oneself: On the Limits of Sexual Autonomy,’ in Undoing Gender, New York: Routledge, 2004, p. 18.

[20] Samir Gandesha, ‘The Gift of Covid-19,’ posted at lacansalon.com on April 20, 2020. http://www.lacansalon.com/listening-to-covid-19/the-gift-of-covid-19. ‘Viral pandemics such as Covid-19, and the climate change from which they are inextricable, know no borders. The well-being and indeed thriving of my body is contingent upon that of non-human animal species and the eco-systems they inhabit and constitute. In contrast to the amazement at the existence of why there is something rather than nothing, the gift of das Gift can be regarded, then, a kind of brutal lesson in universalism. It discloses what could be called a negative humanism grounded not in an ontology or essence of the human, the mystical ‘sendings of Being,’ ego autonomy or will to power but in the inescapable universalism of a trembling fragility and profound vulnerability to suffering, and, ultimately to that final endgame: Death itself.’ I would like to express my thanks to feminist art historian, Vanessa Parent, for bringing this article to my attention.

[21] See indicatively, Caroline Randall Williams, ‘You Want a Confederate Monument? My Body is a Confederate Monument,’ New York Times, June 26, 2020. Last accessed at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/26/opinion/confederate-monuments-racism.html, and Eddie Chambers, ‘Statues, Statues, They All Fall Down,’ The Progressive, June 12, 2020. Last accessed at https://progressive.org/dispatches/statues-statues-they-all-fall-down-chambers-200612/. To the different critical pressures worldwide to critically rethink the histories that public monuments (don’t) tell, as anticipated by the politics of “unforgetting” of Weiss’s own practice, one must add the censorship scandals surrounding art production and exhibition practice in Poland today, ranging from the efforts to remove feminist artworks by Natalia LL from the Warsaw National Museum of Art to the nationalist cleansing of Polish memory manifested by the critique of the Holocaust memorial Judenfrei by Dorota Nieznalska and the persecution of its commissioning curator Tomasz Kitliński. See for instance https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/lawsuit-threat-to-free-speech-in-poland. The latter particularly resonates with the re-memorying of Polish cities and urban sites enacted by Weiss in Shrouds (Caluny), 2012 and Sustenazo (Lament II), 2010–2012.

[22] Vanessa Gravenor, Two Laments.

[23] Moritz Schramm’s concept of postmigration frames Marsha Meskimmon’s brilliant theorizing of the figuration of the worldmaking denizen and the experimental agency of art beyond representation in a cosmopolitanism that stresses the significance of embodied responsible and intersubjective agency for an ethical worldmaking project from which I am rather freely drawing in this read of Weiss’s belonging and the aesthetics of its social engagement, see Marsha Meskimmon, ‘From the cosmos to the polis: on denizens, art and postmigration worldmaking,’ Journal of Aesthetics and Culture, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2017, pp. 25–35.

[24] Ruth Lister, Citizenship: Feminist Perspectives, Pasinsgstoke and New York: Palgrave, 1997, in Meskimmon 2017, p. 28.

[25] Meskimmon 2017.

[26] At the time of writing this piece, I learned of Poland’s move to withdraw from the Istanbul Convention, a convention that aims to protect women from violence. This only confirmed the sense urgency and despair emanating out of the reports on the struggle for human and especially women’s rights in Poland, along with appeals for anti-racist advocacy by friends and colleagues, which have been to the fore over the past several years. It sadly reinforces the urgency for Nirbhaya’s installation in Poland, as well as in the US. Remember the call of Rebecca Solnit for a national rape memorial in 2016? https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/jun/08/america-needs-national-monument-honor-rape-survivors-stanford-case. While permanent and ephemeral counter monuments to women’s rape in peace and war have begun to be raised in different contexts from America to Kosovo, the international sexual war continues, and the accelerated battle against sexual violence is neither given everywhere nor fully successful anywhere, not to mention that no change is granted for ever. The battle continues but the public lament has only begun. Nirbhayas poetically commemorate Nirbhaya’s rape and death to lament the barbarity and trauma of all rapes.

Kalliopi Minioudaki, PhD is a feminist art historian specializing on postwar art from a transnational perspective, working as independent scholar and curator in Athens and New York. Her extensive writings on women artists active in the 1960s, have appeared in distinguished publications and museum catalogues throughout Europe and the US. She is editor of “On the Cusp of Feminism: Women Artists in the Sixties” (Konsthistorisk Tidskrift, 2014), coeditor of Seductive Subversion: Women Pop Artists, 1958-1968 (Abbeville Press, 2010), and author of “Pop’s Ladies and Bad Girls: Axell, Pauline Boty and Rosalyn Drexler” (Oxford Art Journal, 2007). Select curatorial projects marking her practice include Sophia Petrides: No Hope For Death (Athens, Art Cinema Aavora, 2017) and Carolee Schneemann: Infinity Kisses (the Merchant House, Amsterdam, 2015). From 2015-2018 she curated the work of numerous Greek and international artists for the summer video and performance art programs of the Stavros Niarchos Cultural Center in Athens. From 2019 to 2021 she was chair of the Committee on Women in the Arts of the College Art Association.