Eulalia Domanowska

A Spiritual Feminism

by Eulalia Domanowska

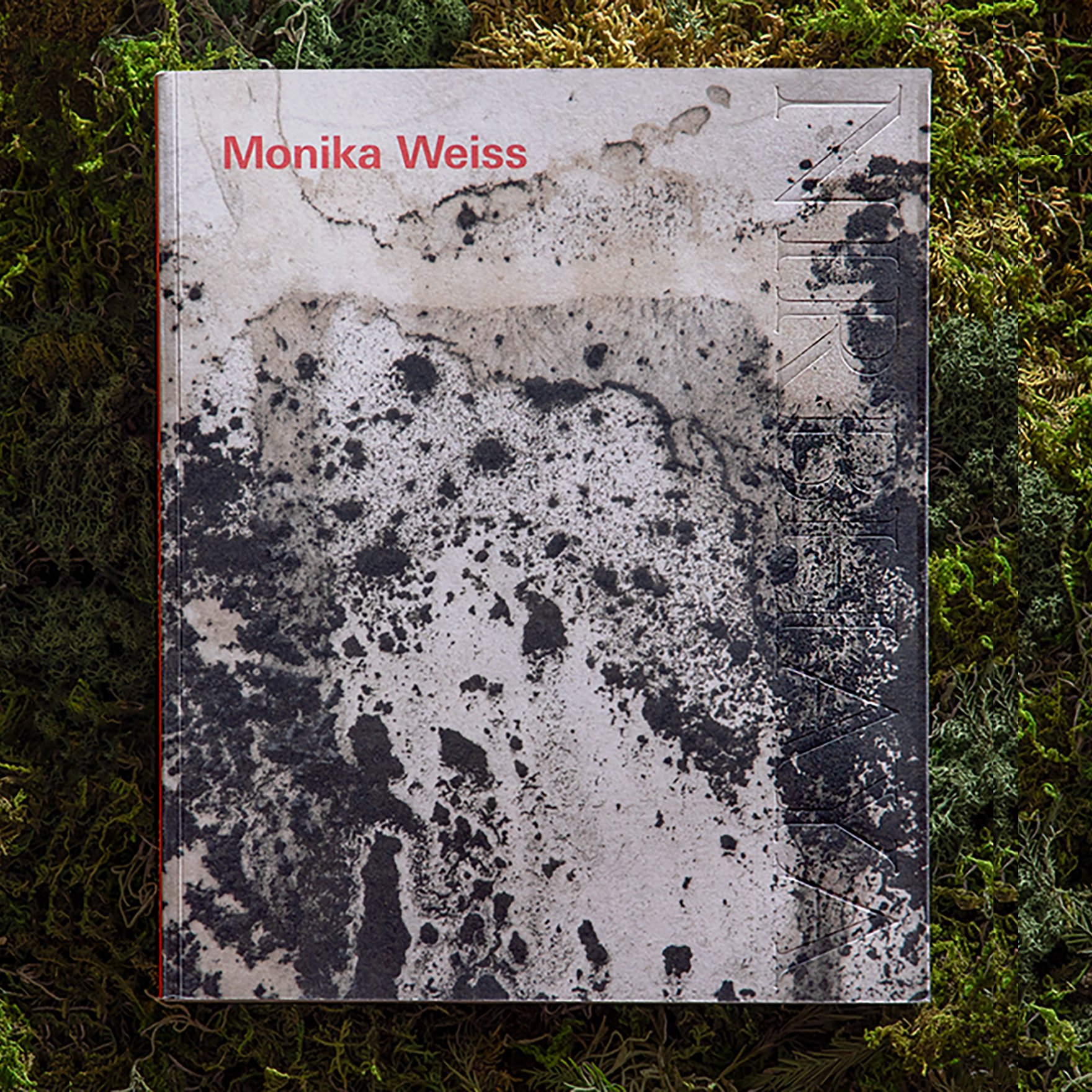

in in Monika Weiss-Nirbhaya, Centre of Polish Sculpture in Orońsko, 2021, pp. 117 - 124

Monika Weiss's recently completed permanent monument titled Nirbhaya is a lyrical and tragic work, one that is visually strong in terms of its execution; the aim of which is to commemorate, as the artist states, two rapes: one on a woman and the other on the city. The work was created following the artist’s sojourn in India, where Weiss had been invited to create an artistic work in New Delhi’s public space. In 2015, she conceived the work Two Laments (19 Cantos), inspired by Jan Kochanowski's Treny [Laments]. A year later, Nirbhaya was conceived, with Weiss deciding to base it on two events: the erection of the India Gate by the British, a monument modelled on The Arc de Triomphe in Paris, and the gang rape of a girl on a bus, a rape which she did not survive.

This was a rape that shook the country eight years ago. A 23-year-old physiotherapy student was returning with a friend from a fashionable movie theatre in southern Delhi. It was late, they had been unable to catch a taxi or a rickshaw, but they did manage to stop a bus operated by one of the many private bus companies. On this journey, they were attacked by six men. The young man was beaten with an iron bar, and the young woman was raped over the course of two hours, the men took turns; and they tortured her with the same iron bar and bottles. One of the torturers later testified that he remembered a red ribbon. This ribbon had been the young woman’s intestines. They had been pulled out. All the while, the bus continued to meander its way along the streets of the city. Eventually, the victims were thrown from the vehicle. The girl was transported to a hospital in Singapore, where she died as a result of her internal injuries. The perpetrators later testified that they had wanted to teach her a lesson; to punish her for being in an inappropriate place – a public place.

Nirbhaya / Fearless (this is the name the media gave the girl, since Indian law does not allow for the disclosure of the names and surnames of victims) would become a symbol of India’s gravest social crisis – one compounded by its caste system – that of a widespread rape culture, coupled with a general contempt for women. This is certainly a complex, deeply rooted phenomenon that has manifested itself in many forms of specific sexual violence; the most ghastly of which is gang rape. The crime against Nirbhaya was committed just before the New Year. Tensions spilled over; and people took to the streets to protest the outrage. Delhi is known as the rape capital of the world. It is estimated that every 20 minutes a woman is raped in this urban sprawl, which is a home to approximately 25 million inhabitants. The situation is no better in other Indian cities, nor indeed in the rest of the world.

“In Indian culture, sex is taboo, and all kinds of violations in this sphere have been shrouded in silence”, explains journalist Paulina Wilk. “The mass protests after Nirbhaya's death were a part of a collective awakening. Women's organizations, women activists and ordinary Indian women (rich and poor, well-born and low-born – it was a remarkable coming together!) took to the streets demanding change.”[1] They sought true equality and a reconstruction of the patriarchal system. “India remains one of the most dangerous countries for women. A country where mothers do not let their daughters leave the house unattended after dark; where a girl, when she gets into a taxi, sends her loved ones the taxi side number, or if she can, takes an Uber and shares the location with friends. It is a country where it is better to dress modestly and not laugh too loudly, since unguarded behaviour gives the criminally-minded both an excuse and an alibi. India is a country where you don't come back from school or go outside unaccompanied, and where you always have to look over your shoulder. Women – of all ages, from girls to old ladies – have a reason to feel that the hunting season is in full swing.” [2] In 2015, 327 thousand acts of violence against women were reported in India; and it is estimated that this represents only 1% of the true figure. [3]

However, as we well know, this problem is not unique to India. Rapes after the Balkan War were finally declared a war crime by the courts, even though they had been practiced for many centuries. Although men and children are also victims, women are most often affected. Sexual violence has been and is a political tool in many parts of the world; it is used in armed conflicts to degrade the enemy. The #Me Too movement, which started in the United States, has made people aware of the massive phenomenon of sexual violence and harassment.

The second event that Monika Weiss foregrounds is the construction in Delhi in 1931 of India Gate triumphal arch, which had been modelled on Paris’s Arc de Triomphe. The gate had been designed ten years earlier by Edwin Lutyens, an English architect who at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries had designed numerous English mansions adapting traditional historical styles. Lutyens had also remodelled New Delhi when in 1911 it had been favoured as the new capital city of India over Kolkata. The city of Delhi, founded over 3,000 years ago, is mentioned in the Mahabharata epic poem. As a city it has experienced various vicissitudes of fortune, being the capital of many state organisms. The Mughal Muslims ruled here for seven centuries, until the British domination of India in the 19th century. Following an insurrection in 1857, the British completely destroyed the old city, its architecture, resources, culture and art. After King George V's decision to move the capital of British India to Delhi, the old historic districts were completely demolished, and Edwin Luytens designed a new colonial architecture, one that accorded with European classical designs. As Monika Weiss has noted: “In response to the architecture and urban structure of Old Delhi, full of intricate and non-geometric lines, Edwin Lutyens created New Delhi, mirroring the geometrical architecture of Paris, one that was full of European flavor. He placed the India Gate at its center. From my point of view, at this juncture, an architectural rape took place on the city itself. In the proposal for the project, Lutyens wrote about teaching a lesson.[4] (The torturers of Nirbhaya would also speak about teaching someone a lesson. E.D. note)

India Gate in New Delhi was built to commemorate the 70,000 Indians who lost their lives in the service of Great Britain in the years 1914–1921. The cornerstone for this monument was laid by Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn. On the arch there is to be found the following English inscription:

To the dead of the Indian armies who fell and are honoured in France and Flanders, Mesopotamia and Persia, East Africa, Gallipoli, and elsewhere in the Near and the Far East and in sacred memory also of those whose names are here recorded and who fell in India or the north-west frontier and during the third Afghan war.

It is impossible to miss the 42-meter-high structure, which is situated in the heart of the city, located as it is on the stately Rajpath Boulevard that runs from the Viceroy's House, which is now the residence of the President of India, a building which was also designed by Lutyens. The green fields around India Gate are enjoyed by Delhi’s residents and tourists as a pleasant picnic and recreational area. Festive military parades are also held here. India Gate, although slightly lower in height than the Arc de Triomphe (51 meters), is one of the city’s most monumental buildings. That said, it is not only a tactless war memorial, but as it is modelled on European architecture it must be seen as a symbol of British colonial domination in India.

It should be remembered that the first triumphal arches were built in ancient Rome as a symbol of military triumph; triumphs which saw the victorious generals and their armies march under the particular arch. The decorative gates built by the Etruscans were probably the forerunners of triumphal arches. Later, this type of structure was erected in other countries and throughout historical periods. Dozens of modern arches can be found in France, Spain, Greece, Germany, North Africa, Asia, and also in Malta, Russia, Ukraine and Poland (arches that date from the Napoleonic Wars).

It is interesting to note that classicist architecture was created in the times of the European Enlightenment – the Age of Reason; and a time which saw the formation of democracy and liberalism based on ancient and Renaissance models, when societies were far from democratic (excluding those of 5th century Athens), and above all on the Roman Republic). It was these forms of architecture and art that were adopted in what was a secularizing 18th-century Europe. Apparently, such characteristics as harmony, sublimity and pathos matched well with the ideas of the Enlightenment. Triumphal arches were erected mainly by rulers and despots who wanted to allude to the might of the Roman Empire and its visual forms. The Arc de Triomphe in Place Charles de Gaulle, as well as the second Parisian arch in Place du Carrousel – commissioned by Napoleon; who dreamed of an imperial fame equal to that of the Roman emperors, and who wished to celebrate the victories of his armies – would become symbols of power and domination.

In 18th-century France, the term architecture parlante was coined, meaning quite simply: speaking architecture. Neoclassicists, including Claude Nicolas Ledoux and Étienne-Louis Boullée, stated that the style of the building designed by architects should be adjusted to its function. Thanks to this way of constructing buildings, modern man, looking at a given object, was supposed to be able to seamlessly guess what kind of a place it was that he was beholding. Seemingly inanimate buildings try to “speak” to us through their form. They become symbols. Admittedly it was all a bit muddled. After all, banks and museums were built in the shape of ancient temples, intended to add dignity and prestige to these newly emerging institutions. The language of architecture is formal in itself, but it is also a conveyor of cultural patterns – it evolves in much the same way as a spoken language.

The language of architecture became an inspiration for artists of the second half of the 20th century. I am thinking especially about Jenny Holzer, who placed her verbal messages in architectural fields, and about Krzysztof Wodiczko, whose monument therapy involved the creation of projections on buildings and monuments, aimed at discovering their “second life”, invisible and translucent to those of us who are used to familiar surroundings in our daily routine; so much so, in fact, that we can no longer read the architectural codes. Wodiczko called his projections a psychoanalytical session, revealing an unawareness of what the building hides (indeed, revealing an unawareness of the building itself).

A clear parallel of Wodiczko's work with that of Monika Weiss's Nirbhaya is his design Arc de Triomphe. Institut mondial pour l’abolition de la guerre [World Institute for the Abolition of War]. An installation designed as the outer layer of the Arc de Triomphe, here the artist looked to show that we must break with the glorification and celebration of aggression and jingoistic politics. This institute would inspire all activity that would bring an end to war.

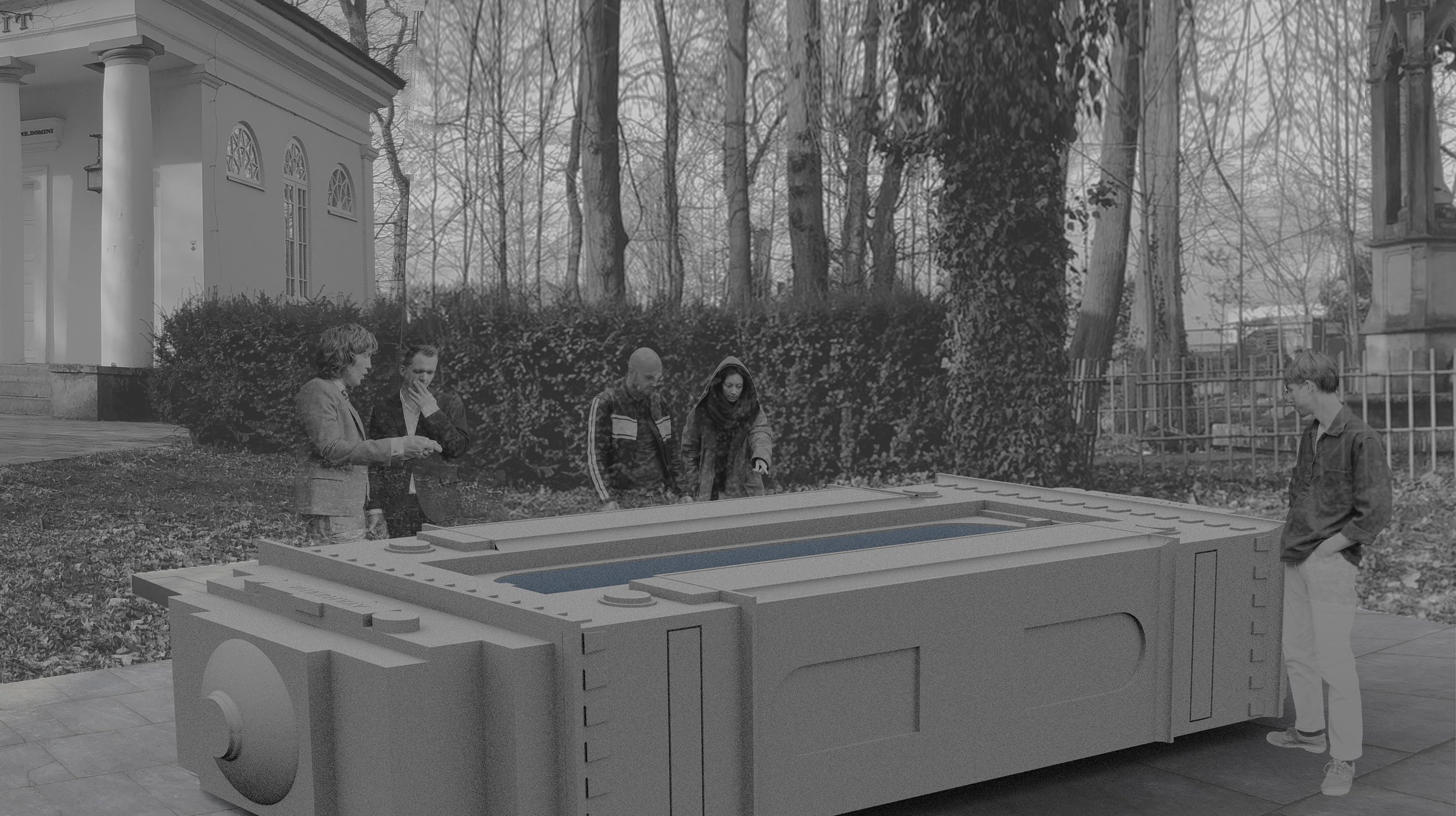

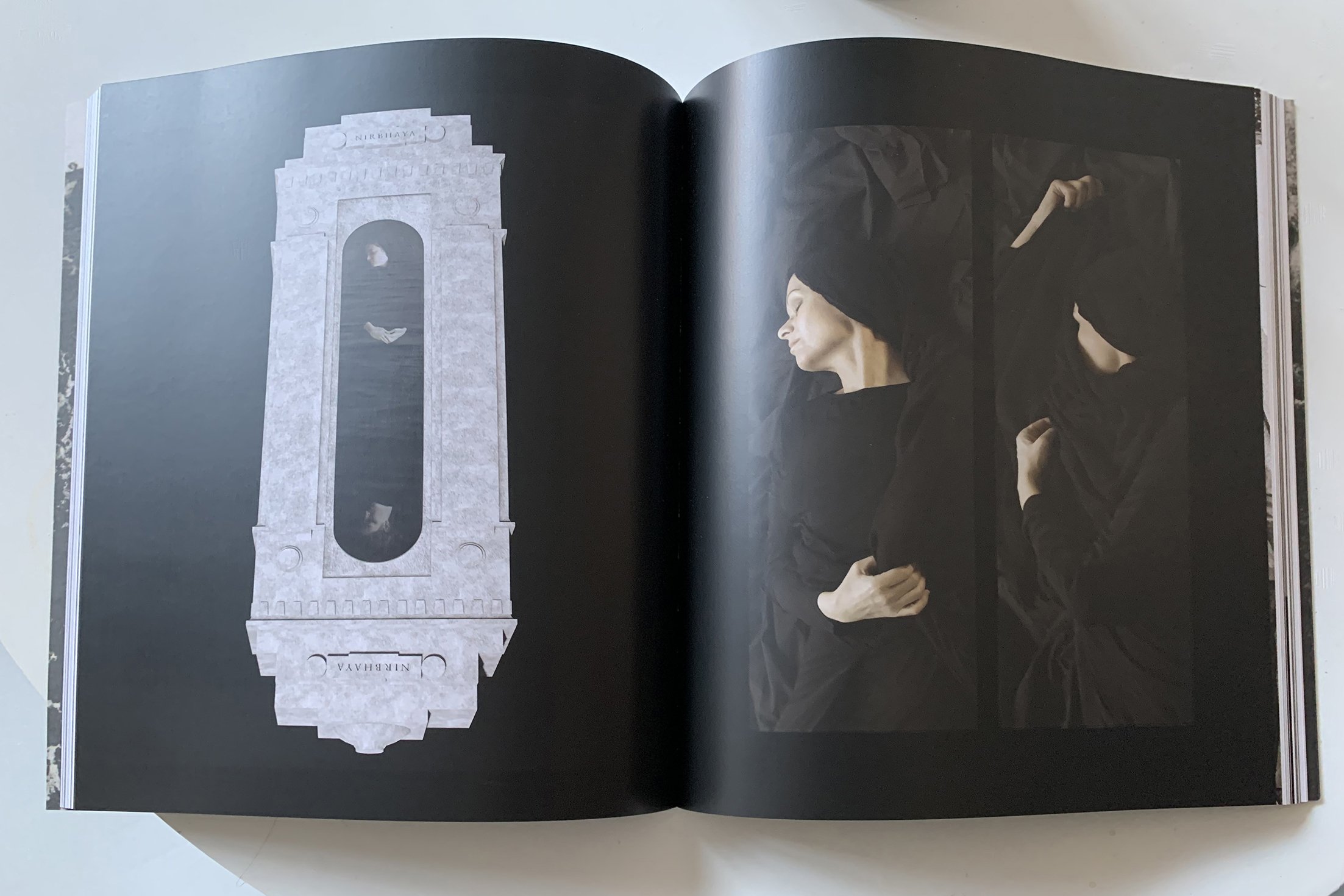

We see this idea in Monika Weiss‘s monument – or perhaps counter-monument. Weiss designed a large sarcophagus in the shape of a double India Gate. In this way, Weiss broke with the notion of the triumphal arch. However, by reducing it to a horizontal form, which in the language of counter-monuments means its deheroization and demasculinization, we see a rejection of the glorification of wars that contemporary societies still experience. Monuments and triumphal arches do not speak about horror, suffering, bestiality, a bloodied body. The neoclassical historicizing architecture as observed with India Gate is far removed from our emotions and body.

Elegant and harmonious, it does not tell the story of suffering. History melts away, fades away, and becomes invisible. You can even have picnics around India Gate. Monika Weiss built the form of a sarcophagus, which is a much more eloquent and distinct image or reference to the catastrophic realities of every war. The artist, who has previously used the form of a sarcophagus in other projects, such as White Chalice (Ennoia) (2004) or Lethe Room (2004), disarms pathos, and reminds us here of the results of conflict – death.

As Robert Musil wrote: “When it comes to monuments, what stands out most is the fact that you don’t notice them. There is nothing else in the world as invisible as monuments […].” [5] James E. Young, the originator of the term “counter-monument” believes that traditional monuments do not remind us about commemorated events, but quite the contrary – under the form of an objectified myth and simple explanations, they eliminate an in-depth understanding of history. In this way, monuments unburden memory, becoming objects of the transferring of responsibility, and constituting not a form that gives memory an impulse, but one that leads to its abandonment; and as a result – to oblivion.

Thus, Monika Weiss transforms the form of India Gate in order to make it anti-monumental and the original idea almost indiscernible. She uses this negative form as a space for a tomb filled with water, in the depths of which she places the projection of a dreamily moving woman dressed in a black shroud. In this way, the artist resigns from pushy and unequivocal didacticism, inviting recipients instead to interact; making them an integral, and, in fact, a key part of the commemoration process. She creates a space for visual contemplation, giving viewers an opportunity for emotional engagement and reflection. We can discover the origin of this multi-purpose, multi-media installation, one which is a tribute to all abused women, through the title Nirbhaya. If we are inquisitive enough, we will discover the story behind this work.

Before creating each project, the artist carries out meticulous research, often collaborating with historians or archivists, all the while making recourse to art in order to relay history and memory and to integrate them into both reality and the present. As she admits: “History in my projects is shown from the collective perspective of those who are or have been marginalized, oppressed, forgotten, erased, or annihilated. I work with traces, remnants, post-stories, post-memories, archives and fragments. Being neither a witness nor a survivor, I invite others to visit my film and sound installations, sculptures, drawings, and public happenings […].” [6]

Monika Weiss usually comes to the traumatic stories that she reveals through recollections and recalling, thus paying tribute to the victims. In fact, through her work, she has actually become an intermediary between the viewers (whom she often invites to participate, and therefore to empathise) and the event. Her stories are tragic and nostalgic. Working with them is certainly not easy. The artist does not resign from the visual aspect in her holistic projects, but instead places a special emphasis on emotional factors, compassion, and presence.

Other contemporary artists have made use of a meaningful and silent presence. A good example is the artistic initiative of Paulina Pukytė, undertaken in Kaunas, Lithuania during the 11th Kaunas Biennial in 2017, in a city where the Jewish community had been eradicated during World War II. The artist asked: “But how to remember what is not there? How not to forget what is there? How to forget? How to commemorate something we wish had not been? And, in the face of over-saturation, what kind of monuments do we need today?” [7] One of the artistic outcomes of this was a performance called At Noon at the Democrats’ Square. For 70 days, every day at noon, an opera singer for 10 minutes sang songs in Yiddish. “My goal was to show the omnipresent absence – the absence of not only commemorative symbols, but also the absence of people who used to live here – Jews, their language that no one understands here today.”[8]

Song and music are ephemeral means of expression that often accompany the projects of Monika Weiss, making recourse as she so often does to a musical and visual form of lamentation. As she explains: “In my projects, lamenting voices fill this void between a memory that remembers only what was said and a forgetfulness that only concerns what was never said.”[9] Music is the most abstract type of art, although it also has the ability to evoke images and emotions. The artist has repeatedly mentioned and described the reasons for the use and history of lamentation and its manner in interviews, including in the text presented at the conference Sculpture Today 4. Anti-Monument: Non-traditional Forms of Commemoration.

Weiss employed the motif of water and reflection in water known from symbolic art, such as the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites (late Romantics as defined by art historians). Lamentation is often associated with the image of water, especially in Arab-Islamic literature. Perhaps it is a reference to the ancient tradition of asking higher powers to send heavy rain so as to wash the graves and restore lost lives. The lamentation awakens the sleepers. Paradoxically, it evolves, referencing the past and giving hope for the future.

Monika Weiss's art is an innovative combination of modern technologies, video art and the archaic act of drawing; but it also incorporates sculpture, performance and music – the art that she became familiar with as a child. Music and poetic projects have allowed her to express the inexpressible. Precisely composed sound transfers filmed actions to other emotional spheres. The artist uses Greek names for her works, which indicates a willingness to reach for the sources of European culture.

As I mentioned earlier, one of the basic elements of her work is lamentation – a musical form that is an expression of despair in the face of loss. In many cultures, women have traditionally made recourse to lamentation as a ritual following the death of a loved one. This motif also appears in Nirbhaya in the form of the projection of a mourner dressed in a black gown and draped in a veil / shroud. This nostalgic visual form was often to be found on Classicist and later Romantic tombstones. In the work Le Serment des Horaces [Oath of the Horatii] Jacques Louis David painted a group of helpless women lamenting the fate of their sons and brothers heading off to war in the service of their country. The fatum of Ancient Greece repeatedly justified this tragedy.

Monika Weiss's works have often been shown alongside the works of contemporary feminist artists such as Carolee Schneemann, Ana Mendieta [10] and Mona Hatoum. They all share a notion of feminism, performativity, and an interest in the body; although the art they practice diverges. Schneemann's projects are characterized by a liberating sexuality, Mendieta’s by their expressiveness, and Mona Hatoum’s by their surrealism. Monika Weiss's projects can be defined in turn by their nostalgic romanticism combined with their formal simplicity of minimalism. They can also be described as romantic feminism, or more pointedly spiritual feminism. [11]

Monika Weiss constructs her projects with care and precision, using various cultural references; thus embedding her story in a universal framework. Through intermedia projects, the artist endeavors to find a continuity between the present day and cultural tradition, between the presence of the here and now, and history and memory. However, the artist has stated that she does not perceive her work as historical exhibitions. Indeed, her outlook has nothing to do with a sentimental approach to history. Weiss does not illuminate upon or disclose anyone’s private moments; she does not reveal human fate. However, she evokes traumas. Weiss gives a voice to women and uses lamentation as a form of postmemory, conveying the unspoken, and opposing the acts of conquest and power. The most important factors, when interacting with her works, are our own experiences and emotions; only they can move us so deeply.

Eulallia Domanowska, Białystok, 2021

Notes:

[1] Paulina Wilk, Gwałty w Indiach są coraz brutalniejsze. Mimo surowszego prawa [Rape in India is an ever-more brutal affair, in spite of harsher punishments] Polityka [online] 11 January, 2020, https://www.polityka.pl/tygodnikpolityka/swiat/1938168,1,gwalty-w-indiach-sa-coraz-brutalniejsze-mimo-surowszego-prawa.read [accessed on 5 July 2020].

[2] Ibid.

[3] Amnesty International report published in 2017 as presented in: Agata Szczerbiak, Gwałty były i są narzędziem polityki w Indiach [Rape has been and continues to be a political instrument in India] Polityka [online] 29 April, 2018, https://www.polityka.pl/tygodnikpolityka/swiat/1747200,1,gwalty-byly-i-sa-narzedziem-polityki-w-indiach.read [accessed on 8 July 2020].

[4] Monika Weiss, Nirbhaya. Triumphal Gate Lying Down – Memory, Amnesia, Flatness, Wrath. Notes Towards a Project, in Sculpture Today 4. Anti-Monument: Non-traditional Forms of Commemoration, Orońsko: Centrum Rzeźby Polskiej, 2020, p. 406.

[5] „Es gibt nichts auf der Welt, was so unsichtbar wäre wie Denkmäler”. Cited after Robert Musil, Denkmale, Prager Presse 1927, no. 339.

[6] Monika Weiss, op. cit., p. 192.

[7] Paulina Pukytė, “There and Not There: The (Im)possibility of a Monument Aims and Results of the 11th Kaunas Biennial (2017) in the Context of Current Commemoration Discourse in Lithuania”, in Sculpture Today 4. Anti-Monument: Non-traditional Forms of Commemoration, Orońsko: Centrum Rzeźby Polskiej, 2020, p. 198.

[8] Ibid., p. 95.

[9] Monika Weiss, op. cit., p. 192.

[10] The closest analogies with Monika Weiss's art can be found in the works of Ana Mendieta, who explores feminism, violence, death and the issue of identity. Her earth and body sculptures are an extension of nature and a reactivation of old beliefs. In performance art, she sometimes uses blood, considering it "a very powerful and magical substance," emphasizing the power of female sexuality and the horror of male sexual violence, creating a series of works devoted to these topics in the 1970s. The reason for their creation was the artist's protest after the rape and murder of student, Sara Ann Otten.

[11] The term was used by Monika Fabijańska for an exhibition in 2020 entitled ecofeminism(s) which took place at the Thomas Erben Gallery in New York. It should be noted that two years earlier, this curator, art historian and diplomat had organized another very important exhibition entitled Rape. An Un-heroic act REPRESENTATIONS OF RAPE IN CONTEMPORARY WOMEN'S ART IN THE U.S. shown at Anya and Andrew Shiva Gallery, also in New York, which proved to be a ground-breaking event in the study of the visual language of rape and violence used by artists.

Eulalia Domanowska ia an art historian, art critic, and curator of over 100 exhibitions in Poland and Europe, as well as academic lecturer. Sje was director of the Center of Polish Sculpture in Orońsko between 2016-2019. Member of the AICA and IKT organizations (Association of Contemporary Art Curators), she has been the editor-in-chief of the Orońsko Quarterly from 2016 - 2019. Since 2016, Domanowska is the founder and main organizer of the international scholarly conference Sculpture Today. Between 2002-2006 she conducted research in the field of Swedish language, art, museology, ethnology and gender art at the University of Umeå in Sweden. She is currently Director of the State Gallery of Art in Sopot. She is particularly interested in modern and contemporary art, art in public space, art in the landscape and sculpture parks.