Griselda Pollock

The Fidelity of Memory in an Endless Lament. Nirbhaya, New Delhi, 2012, and Now…

by Griselda Pollock

in Monika Weiss-Nirbhaya, Centre of Polish Sculpture in Orońsko, 2021, pp. 12 - 50

In my art, lament questions language, polluting its purity. (...) In my projects, history is shown from the collective viewpoint of those who are or were marginalized, oppressed, forgotten, erased or destroyed. I work with traces, remnants, post-histories, post- memories, archives and fragments.

[I] THE UNMONUMENTAL

Mesmerizingly slow, soliciting prolonged immobility in enthralled gazing, calling for acute attention to subtle changes in the folds of cloth or movements of the draped body, in performance or filmed, provoking intense engagement with the choreography of poignant gestures of elegant hands winding and unwinding, rising and falling, with its own sonic environment that is neither music nor language, Monika Weiss’ works have long solicited our attention to historical events: forgotten, remembered, not yet mourned, or immemorial, so that we experience their condition affectively through a musically choreographed image of time: time is both her frame and medium.

Nirbhaya is a complex project deeply resonant for the present. Inspired by a murderous event in the Indian city of Delhi in 2012; and the subsequent worldwide response (that I shall address in the final section), the artist calls us to be a remote, removed, belated but permanent witness to that event. As an artwork, however, Nirbhaya also converses creatively with the visual rhetorics and pathos formulae of European art during the periods of its most intense commitment to imagining life, death, power, desire, violence and ecstasy, fear and sorrow. [1] For this reason, I shall approach it in part through art history.

In Nirbhaya, we watch and listen to Two Laments (19 Cantos) 2015–2020, a continuous video-poetic projection, sound, single channel cinema style installation. We stand before Dafne (for Nirbhaya), 2020, large-scale, vertically hung, graphite powder, archival glue, water, dry pigment — a series of abstract, material drawings that evoke both a body and the rough surface of a tree’s scaly bark. The title of these large-scale drawings evokes the mythological figure of the river nymph Daphne (fig. 2), from the Metamorphoses by Ovid. She was pursued by a rapacious Apollo [fig. 8] and called out to her father and mother to save her from being raped by the sun god. They transformed her into the laurel tree. Thus, Daphne escaped a terrible fate but only to die even as she became a non-human, living thing: a tree. [2]

We shall also study a 3D model of the monument, Nirbhaya, to be built in the park. It takes the form of a horizontally placed, water-filled sarcophagus containing a projection, through or on the water, of supine moving bodies of women dressed in black cloth. Sarcophagus is the term for a stone, originally a limestone, container for a dead body typically placed above ground in Greece and Rome; or in Egyptian burial customs, placed around an inner wooden coffin which contained the mummy. We shall consider this evolution through small preparatory drawings for this distinctively supine Nirbhaya monument and anticipate the sonic space of Nirbhaya as a sound station within the park where, one day, the full-scale counter-monument will be fully realized. Thus, we are witnesses, in anticipation of the work to come, as well as in recollection of the event that it will continually memorialize [fig. 4].

This exhibition and its publication offer, therefore, an encounter with a multi-form, multi-media, synaesthesic, emotionally charged and historically resonant artwork. Nirbhaya distils and transforms the aesthetic procedures and formal languages honed by Monika Weiss across her long series of audio-visual-sonic-performance-graphic works over the past twenty years. In her practice, often inspired by the necessity to re-remember real events or focus on specific places of events, Monika Weiss has sought out many forgotten stories and overlooked sites of anguish in the traumatic history of the European world and beyond by focusing, albeit not exclusively, on the violation of the humanity of women. [3]

Perhaps I should rephrase that. By making the moving bodies of women, often including her own, a mobile alphabet of pathos, her art speaks against violence finding adequate forms of memory for understanding, explaining, theorizing and representing the extreme events that historian Saul Friedlander termed as ‘events at the limits of representation.’ [5] This means such events fall at the limit of representability because their extremity or horror exceed all existing precedents that might allow measurement, comparison, scaling, and determination of what the event was. World wars, genocide, mass starvation, catastrophic weather events or earthquakes causing mass destruction and loss of life, chattel enslavement, colonization, apartheid — these are some of the shocking events to which we seek to give shape in order to comprehend their meaning, and also in so many cases, to mourn their effects. Monuments are called forth and provided.

In the late twentieth century, many artists, however, disowned the conventional monument. Cultural theorist Eric Santner argued that the monument or memorial functions as narrative fetishism, a displacement of real mourning and memory: ‘By narrative fetishism I mean the construction and deployment of a narrative consciously or unconsciously designed to expunge the traces of trauma or loss that called that narrative into being in the first place… Narrative fetishism releases one from the burden of having to reconstitute one’s identity under “posttraumatic” conditions; in narrative fetishism, the “post” is indefinitely postponed.’ [6]

Effectively, we build a monument so as to be able to forget, charging its inert form to remember on our behalf. As a fetish, however, it marks the site of that which we should remember while disavowing the pain of remembering at the same time. As a result of this realization, many contemporary artists in the 1990s began to create counter-monuments as artistic interventions that require our work of thinking and feeling. Both thought and affect are incited by the form, process, materialities, duration and pathos of artworks that resist closure. [7]

[II] UNDOING TIME

Theses on the Philosophy of History (also known as On the Concept of History) was written by Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) as he sought to escape in September 1940 from a Europe then ruled by the forces of genocidal fascism. This text only began to circulate in the community of European thinkers following its publication in French in 1947 and in English in 1968. Composed of twenty small sections, the most widely quoted is Thesis VI: ‘To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it “the way it really was.” [Ranke] It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger.’[8] This reverses the trend to monumentalize and, in a sense, to pacify the past. Instead, artists are responding to an urgency to recognize our dangerous present as the living form of unresolved violence. Hence our recognition of all our danger calls the past forward to agitate us now into a state of constant alert and to make our sorrow an incitement to tolerate no longer human violation.

Can I suggest that in such a Benjaminian dialectic the artworks of Monika Weiss creatively transform our sense of history, or shall I say the historical moments she selects for our prolonged attention. Her medium for making us experience them affectively; as well as inciting us to reflection, is a synaesthetically-crafted experience of duration. Both creating a monument because we must mark this event in history and countering monumentality so that we cannot then forget what it calls upon us to know, to acknowledge, to sense, Monika Weiss’ aesthetic formulations in drawing, sound, object and moving image turn our sensate and sympathetic bodies into partners to those she evokes in classical modes through materially evocative figure drawing — and in contemporary electronic forms of sound and the moving image. By these means, and in relation to the event that claimed her attention, she seeks to erase the gap between ‘the event’ (past, elsewhere, other) and its exceptional, indeed horrific rupture of the quotidian, in order to remain beside Nirbhaya. The word names one woman but then becomes, via the extended artwork of this title, the multiple figure of all women in their vulnerability to sometimes violently regulated limitations on their freedom of movement and choice, to the enforced social prescription of their ‘proper’ roles, ‘decent’ behaviours and spheres of confined action, to moral judgement, legal limitation, and, above all physical abuse and violence.

[III] THE WORK OF MOURNING

Monika Weiss’ artworking summons me as an art historian to wander in my virtual feminist museum as I seek to enter its depth and convey its affect and its project. [9] There her artworks might converse with the cultural analyst and art historian Aby Warburg, inevitably, about gestures and the pathos formel of lamentation, or meet with a painting by Sandro Botticelli and other Italian and Dutch artists of the early modern era in Europe, research the history and meaning of the triumphal arch, and face troubling questions pertaining to gender, sexual difference and the ‘rapish’ order of violence against women. In Nirbhaya, evolving since 2015, we shall also obliquely confront a hideous crime transformed, however, by artworking into the work of mourning. [10]

Since mourning is always endless, we are invited by the extended artwork to remain with a spirit, not Warburg’s dancing Nympha, the embodiment of enlivening energy, but nonetheless a messenger of life and death in our times. ‘She’ is evoked by protective naming of course, Nirbhaya: she, the fearless, in order to overwrite the history of a crime that killed her. Monika Weiss now offers us a form for an eternal and restless lamentation to which we are hereby summoned for one woman, the woman shielded by the nomination Nirbhaya, but also all women, because, in the event of 16 December 2012 in the Indian capital of Delhi, this one person had ceased in the eyes of the six men who raped and so viciously tortured her that her internal injuries led to her death to be anything other than what they considered woman [fig. 3].

To make sense of what has haunted this artist and sustained her fidelity in creating this new range of interrelated works, we plumb the depths of affect created by Monika Weiss’ singular and dialogical use of technology — she layers the almost stilled but fluently moving image — and by large mixed fluid media drawing, and by environing sound. These form for her the components of her counter-monument, wherein we may find ourselves obliged to think on a historical scale and plunge deep into the mytho-poetical territory of the Western Classical and Christian imaginaries through the power of the visual and the acoustic.

[IV] THE FORMULA FOR PATHOS

Death, destruction and loss are the foundations for lamentation, and lamentation has been the inspiration for the vocal-musical-poetic form, lament that has extended into drama, movement, and contemporary songs. The oldest surviving example is The Lament for Sumer and Ur, dating from 2004 BCE. This is a communal lamentation for the destruction of the city, one of the earliest urban centres, and is ‘spoken’ by the city’s patron goddess. Lament has also found its place in many subsequent written literatures, from the Hindu Vedas, the Greek epics and the Jewish and Christian Biblical Book of Lamentations, Book of Job and the Psalms to Anglo-Saxon texts such as Beowulf, as well as across Middle Eastern literatures. Later in the West, lament became a recurring mode in Baroque Opera, perhaps most famously in the affecting melancholy of Dido’s Lament from Henry Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas (1688).

Scholars of African-American musical culture have identified an extended tradition of African ‘sorrow songs’ arising not only from literal death but also from the social death inflicted on enslaved peoples lamenting their dehumanisation and loss of freedom. In his foundational text, The Soul of Black Folks (1903), African American scholar W.E. Du Bois concluded with a long chapter on the ‘Sorrow Songs’. Writing of their continuing legacy, Joseph Winters states: ‘Du Bois suggests that the ‘sorrow songs’ articulate a mournful hope to the world. In other words, the capacity of enslaved black Americans to voice and express the pain and suffering embodied within the arrangements of white supremacy is pivotal to the imagination construction of a more racially just world.’ [11] This historical-political dimension of what is being lamented, combined with resistance enacted in the creation of the lament, introduces a critical dialectic when we approach the role and affective force of mourning memorials that also perform as anti-monuments against systemic violence and injustice enacted against women in the world today.

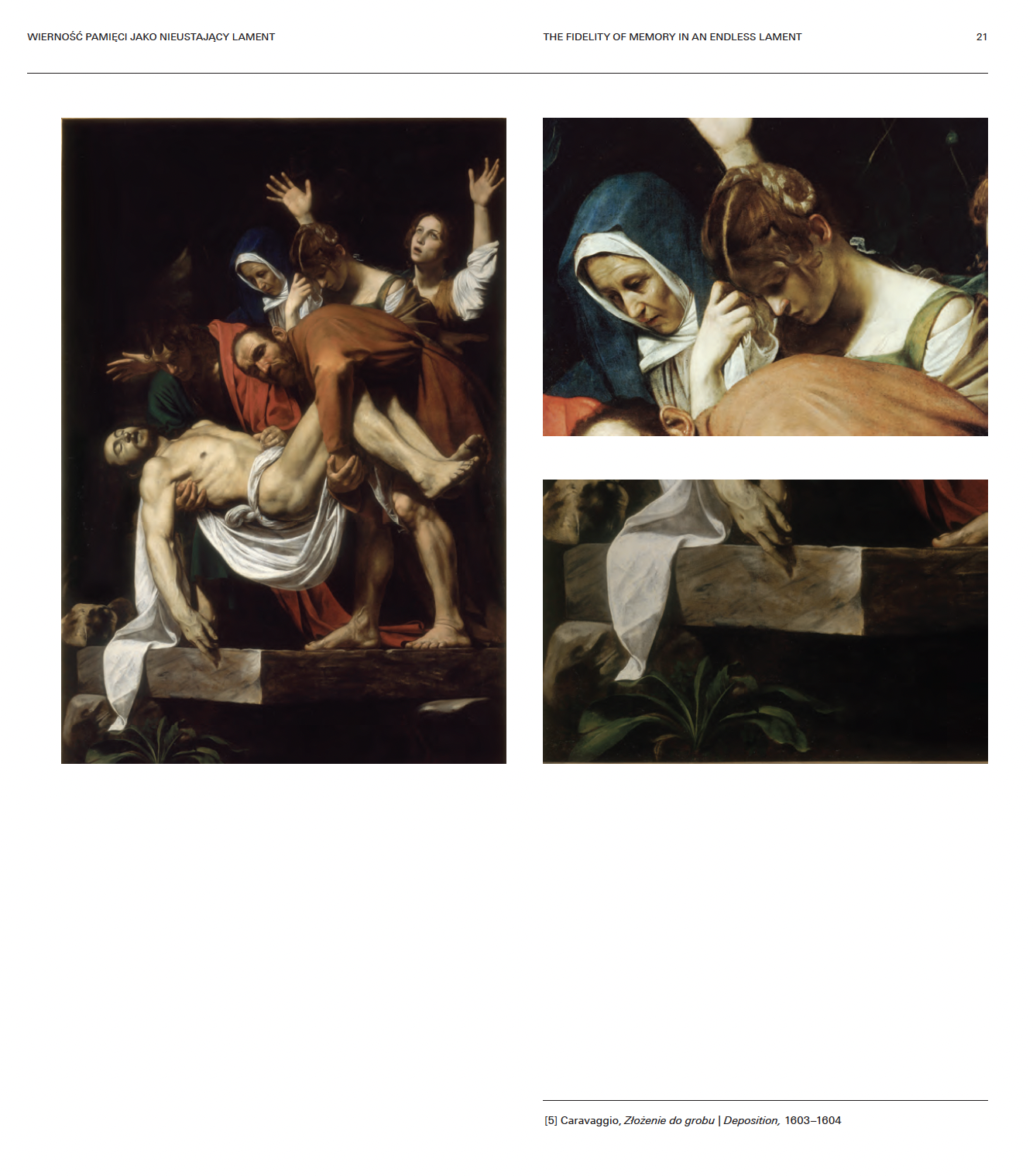

Lamentation has also generated visual images, the foremost amongst which, in Western Christian visual art, focuses on the Lamentation of Christ, associated with the Deposition from the Cross, where the lifeless body is carefully taken down and entombed by a group of figures, all expressing their anguish, watched by a grieving mother. Caravaggio realized this iconography with dramatic realism in his Entombment of Christ (1603–04), commissioned for the Santa Maria in Vallicella, now in the Pincoteca, Vatican City) [fig. 5]. The grieving mother becomes the central figure in the monumental form of The Pietà where the Virgin Mother, alone or, rarely with helpers, holds the lifeless body of her adult son. Michelangelo carved his Pietà in 1498–99 (St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City), [fig. 9]. In addition to iconographically elaborating the theological interpretation of a Biblical narrative, both these images are significant here for two reasons. In the paintings we confront living bodies and a dead body. The dramatic device that signifies this radical difference between life and death is the formal use of the axis vertical versus horizontal.

The second element to note is the differentiation between the stilled forms representing lifelessness and the animated gestures that convey both living and reacting to the anguish of being witness to this death. Theatrical hand gestures dominate Caravaggio’s group. He uses a bowed head, [fig. 5] hands raised to a face and, most dramatically, arms outstretched, and a face raised to the heavens in classic lamentation. Lighting defines an axis upper right to lower left, unifying the painting as it traces the diagonal form of a woman with white sleeves down that fall of the cloths folding over the grave slab and drawing our eyes into the darkness of the unseen tomb into which the body is about to be lowered [fig. 5].

This Baroque drama is very different from Michelangelo’s High Renaissance monument a century earlier where his composition delivered a radical crossing of vertical and horizontal, softened by the pathos formula, the formula for expressing intense feeling, to borrow from Aby Warburg’s vocabulary, of the inclined head of the ageless mother and the simple, almost invisible gesture of her left hand, palm opened as the signifier of incomprehension before the reversal of time: a mother grieving for her adult son. Michelangelo managed the compositional challenge of a woman holding a fully grown man across her lap by means of his astonishing carving of a mass of drapery, across the Mother’s body, beneath the supine son, autonomously folding and hollowing, dramatically falling in an opened arc on the left as cloth escapes the Mother’s hand holding the body in a tense movement of splayed fingers. The minimalization of the overt gestures of lament — inclined head, lowered lids, and the despair of her left hand — refocuses the drama onto the mass of marble cloth [fig. 9].

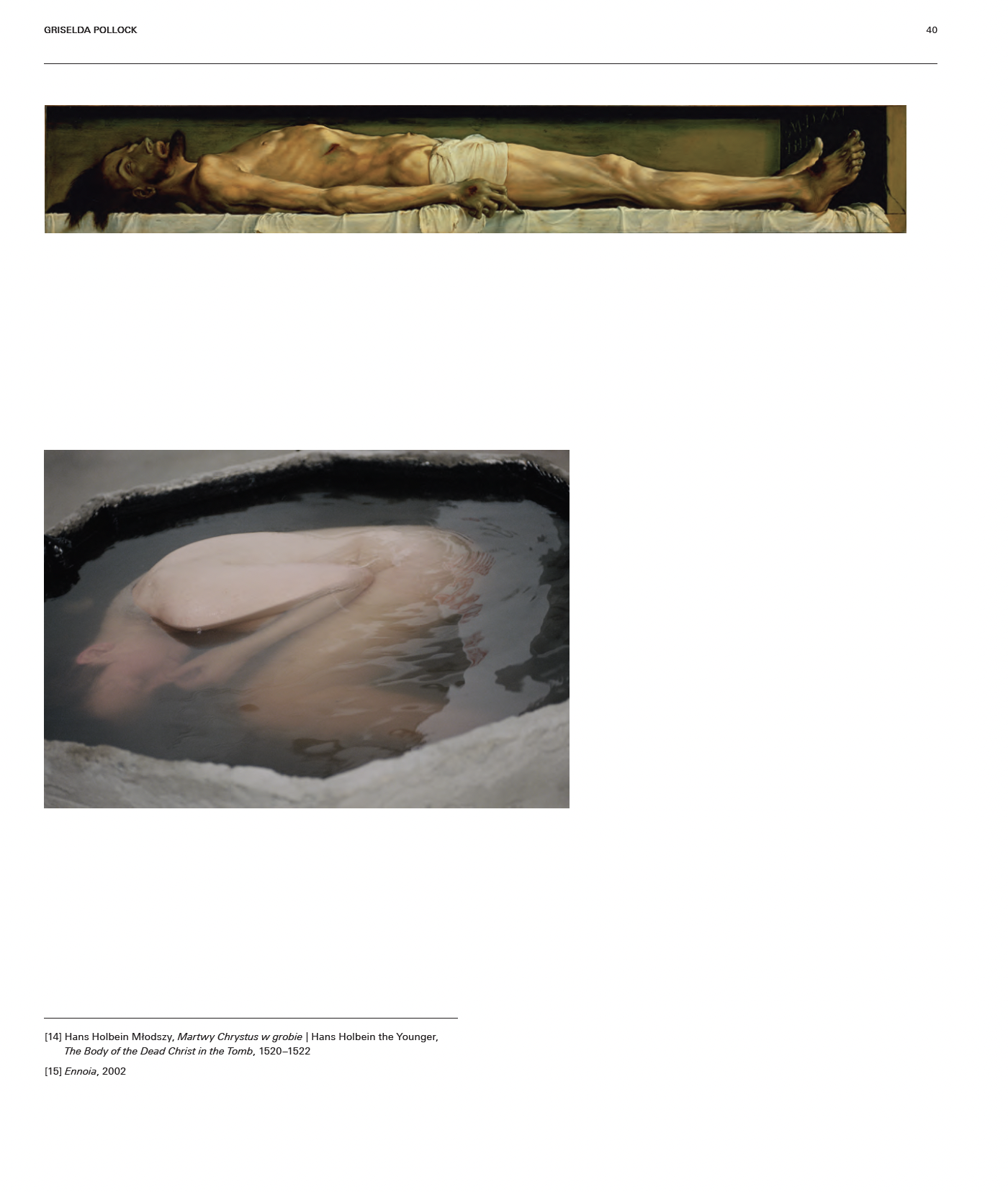

Between Michelangelo and Caravaggio lies the first Protestant reconfiguration of the Catholic iconography of deposition and lamentation created on the very cusp of the emergence of Protestantism and its uneasy negotiation of religious imagery and humanist sense of death. The work in question has haunted artists since its realization between 1520 and 1522, and certainly is a part of the musée imaginaire of Monika Weiss. Unrelievedly horizontal, the composition by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497–1543), titled The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, claustrophobically encases a brutally wounded, undeniably decomposing, mortal body within an oppressively shallow tomb: the dimensions of the painting itself at 30.5 cm × 200 cm. [fig. 14]. I have returned to this painting several times in my own work, notably in the analysis of the ‘sculptural dissolutions’ of the Polish sculptor Alina Szapocznikow.[12] There I drew upon French literary theorist Julia Kristeva’s reading of Holbein’s painting as positing a perplexing contradiction. Kristeva senses that in Holbein’s Protestant confrontation with the entombed dead body of an incarnated deity: ‘Humanization has reached its highest point.’ [13]

Kristeva argues that at the intersection of Catholic theology with its spiritual understanding of the death of Christ and the novel Protestant insistence on the reality of suffering, this painting offers us ‘an unadorned representation of death’ which conveys to the viewer ‘an unbearable anguish before the death of God, here blended with our own, since there is no hint of transcendence’: everything save a tiny touch of light on the toe produces a feeling of permanent death. Christ’s dereliction is seen here at its worst through the insistent realism of the representation of decaying, gangrenous, wounded body. Playing this image of the inert and horizontal, dead Christ against Holbein’s vertical dancing figures in his other representation of death, la danse macabre, Kristeva writes:

“… we are led to collapse in the horror of the caesura constituted by death or to dream of an invisible beyond. Does Holbein forsake us, as Christ, for an instant, had imagined himself forsaken? Or does he, on the contrary, invite us to change the Christly tomb into a living tomb, to participate in painted death, and thus include it in our own life, in order to live with it and make it live? For if the living body in opposition to the rigid corpse is a dancing body, does not our life, through identification with death, become a danse macabre, in keeping with Holbein’s well-known depiction?” [14]

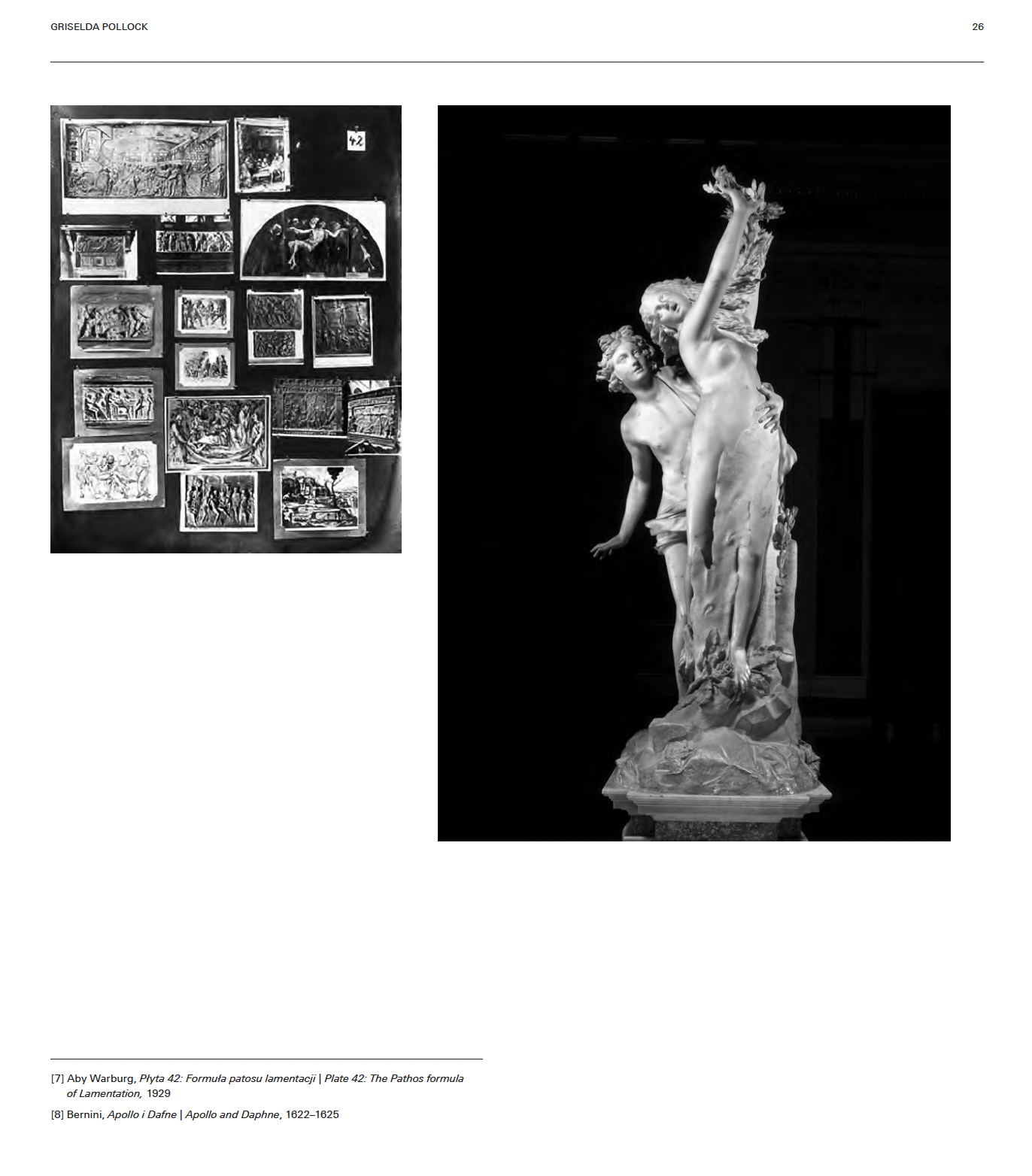

In this art historical digression, I have been assembling a plate in my own Bilder Atlas echoing Plate 42 of Warburg Mnemosyne Bilder Atlas Leidenpathos: The Pathos formula of Lamentation [fig. 7]. None of the three works I have discussed appear in Warburg’s assemblage. Yet I would argue that all of them are deeply relevant to understanding the depth and art historical gravitas we find in the work of Monika Weiss. Monika Weiss has herself studied and made drawings after the Holbein painting. One hangs in her studio. It is clear from conversation with the artist that, like Kristeva, Monika Weiss has also been absorbed by the account of a devastating encounter with the painting in Dostoyevsky’s novel The Idiot (1869), while also being enthralled by Kristeva’s own elaboration of the significance of Holbein’s painting.

Her fascination is also translated into her drawing works such as Kordyan II, 2005, and one might say into a whole series of her performances in which the draped or the naked body, the folding and unfolding of cloth, encasement, and the recurring disposition of bodies on the horizontal axis register her deep involvement in and transformation of the affective and ethical question of our encounter with suffering, destruction of human life, and death. This places her at once both in the heart of the European tradition of figurative, performative art as a mode of thought and affect by means of the language of the body, and the animation of the inanimate accessories, and in the community of the artists in our world, a world shaped by the traumatizing violence in the twentieth century that, I have argued, effectively ruptured the link between the theological imaginary of European Christian art and the post-catastrophic imaginary of our own indecipherably wounded times. Yet, as I propose this argument, that we are dislocated through historical events from the imagination of redemption that created the art of the Renaissance, I need to evoke this artistic tradition precisely to define the difference of contemporary art of a comparable gravity.

There are several contemporary artists whose envy of, and identification with, the classical Renaissance tropes of the expressive body in perspectival space produce theatrical reincarnations of great works of the European sixteenth century by means of the wonders of technology. Monika Weiss’ work is not like that at all. The challenge she has met with a series of major works and a distilled practice across live and filmed performance, sound, drawing and ‘moments’ of history, show that she has understood the profundity of the thinking that once — via a Christian theological imagination — underpinned the European figurative tradition, with its language of the body and its pathos. Yet she also knows that artists must now think and reimagine through currently expanded media and processes in order to invent forms adequate to the challenge of confronting the contemporary traumas of suffering and destruction of which we now are the surviving witnesses, daily. Without the theology, but with the formal legacy, I can then ask if it is possible for art to become what artist Bracha Ettinger has termed a ‘transport station of trauma’ (I shall elaborate this below) rather than an iconographic inscription of the theologies of life and death.

[V] THE LAMENT

Death breaks through the veil we tenaciously imagine is preserving the living from the unimaginable condition of not-being, no longer being human, but matter. The idea of death has solicited from humans and many other animals compulsions to surround, with ritual, sound and gesture, the abyss that opens before the still-living when we face the death of another. In human societies, such rituals may involve burial in earth or water, cremation and mummification as well as attendant performances of formalized liturgies that are of the most intense laments are allocated specifically to women, as if they, who have given life, also watch over the end of life and span the mysterious frontier between the two. The doubled image of the Dark and the White Goddess, delineated by poet Robert Graves and also identified by art historian Aby Warburg in the deepest origins of the ancient Greek Aphrodite/ Roman Venus, places the feminine literally on both sides of the frontier between life and death, at the fold, as Kristeva argues, between life and meaning, between the body and language. [15]

Mourning gives rise to lamentation. Lamentation involves the body expressing (literally bringing forth air) as sound and gesture the attendant emotions of grief: covering the face or raising the arms, bowing the head, rocking back and forth, holding the head in one’s hands, even collapsing completely in utterances of woe. Lamentation is, therefore, not silent. It is also associated with the voice but not with spoken words. In English, there is a phrase ‘howling with grief’. Lamentation is thus associated with groans rising from deep within the body’s cavities at the frontier of pure sound and articulated meaning. At worst, grief wracks the body with uncontrollable sobs, or it can be formally uttered in formulae such as ‘Woe is me!’ Lament moves primordial grief into a minimally aesthetic formalization: a poem, song, or piece of music, which expresses sorrow that someone has died. These profoundly visceral, sonic, rhythmic and wrenching expressions of grief and sorrow morph into cultural forms that fall closer to the sublime than to beauty.

Exploring the modern instances of lament by means of the evocation of philosophical theories of the sublime as well as developments in modern medical and psychological theories that converge on melodrama and Romantic ballet, Linda M. Austin defines this singular combination of ‘the auditory and the gestural’ as a ‘language of trauma’.[16] Drawing the crucial research of Margaret Alexiou on ancient Greek ritual lament, Austin reminds us that: ‘Lamentation that expresses the shock of death has an ancient name, γόος [góos], which referred originally to the kins- woman’s shrill cry for the dead.’ [17] This feminized body-sound is to be distinguished from the formal modalities the Greeks identified, crossing from the intimate and individual to the communal, the political, the elegiac and the aestheticized.

Alexiou argues that góos is different from the penthos [πένθος] defined as ‘collective public grief for the death of a hero’ and ‘from threnos [θρένος], the lamentation sung by professional mourners during the wake. Góos is also not kómmos [κόμμος], the lament exchanged between chorus and actors in Greek tragedy, but is individual lamentation; in Homeric rituals it designates the spoken lament of intimate mourners.’[18] Without the formal sophistication of professional songs, ‘góos envelops the mourner in a private confrontation with the fact of death, with its ineffability’, yet it evokes ‘words of lamentation, rather than to the ritual itself or the emotion.’ Austin concludes however, that in extreme cases, language yields to gesture, or become themselves almost like a cloth, at once a winding for and an indexical sign of the unspeakable:

“The epic can quote the góos, though frequently it presents it as spectacle rather than sound. Thus, the three friends of Job, seeing his misery, lift up their voices and eyes and weep; each tears his mantle and sprinkles dust on his head (Job 2: 11–12). These actions suggest that in an episode or moment of the utmost shock — whether of awe or of grief — language is less expressive than the body. Indeed, the words and phrases of lamentation often wind round in endless repetition or break off. They do no more than point toward some unreachable sorrow.” [19] (my emphases)

Austin also writes: ‘In the epics the góos is an auditory effusion complemented with images — of mourners weeping, flailing their arms, covering their faces, rolling in dirt.’ [20] My emphases in these passages open my eyes and ears to the artworking by Monika Weiss across the many elements that form Nirbhaya. I want to draw attention to terms such as enveloping, private confrontation, intimate mourners, the expressivity of the body, winding round and round, endless repetition, an unreachable sorrow. I am also beginning to identify the aesthetic language that is so as to create spaces and modalities in our tragic modern world that challenge our depleted affectivities banalized and hardened in the cheap theatricality of modern media. This exploration of ancient Greek or Irish rituals of lamentation and mourning also enables us to make a critical distinction between what I have termed aesthetic formulation and spontaneous outpourings of grief, even as we recognize the resonances with, and even debts to, historical modalities for the confrontation with death, destruction and loss. Austin writes of góos that, as ‘traumatic language’:

“[…] sounds spontaneous and involuntary; it is meant to exhibit a mind and body temporarily out of control. Traumatic language signals internal dissociation, a state in which events are registered but not understood. The condition, as well as its symptomatic language, is unsustainable; it does not seem able to subsist apart from belated accounts of it, from a point of cognitive recovery.” [21]

Monika Weiss’ musically measured artwork is not, however, about the extremity or intensity that leads to the dissolutions of self or meaning. Linda Austin remarks that in the sublime mode of lamentation that then enters into modern Western bourgeois culture through nineteenth century melodrama, the mourner effectively ‘disappears into his or her grief’ by personifying grief, creating thereby a ‘theatre of trauma’:

“Lamentation enacts the hysterics and paralysis of woe through aposiopesis, the movement toward silence. We hear it, paradoxically, in refrains, ellipses, and outbursts. Both emotional states — sublimity and grief — surface in an identical posture because each represents a momentary but profound discomposure. That rhetorical marvel “woe is me”, declaring the total self-absorption of the mourner, personifies the speaker as woe — her individuality is utterly erased in this theatrical identification.” [22]

I want to argue the Monika Weiss’ work challenges us precisely because it has not become merely symptomatic, a hysterical disarticulation. Moreover, her work is not about recovery. Nor does it offer belated accounts of states of dispossessing extremity.

Indeed, I am arguing that her artworking is a rhetoric she has created for a continuous present that is realized in a formalized, aesthetically intense, audio-visual musicality that, even as its chosen terms are body, sound, gesture and movement, avoids all melodrama in its gestural form, refutes all hystericization of the body, and does not silence language. Hence it does not still thought. Thus, while quoting French philosopher Jean Luc Nancy on the Sublime, Austin suggests that lamentation moves ‘toward an abyss of language… overwhelmed with the idea of loss rather than the lost object’, I think, on the contrary, that we are confronted in the Nirbhaya precisely with a form of making present something radically other than both loss and the lost object. [23]

I have been purposely weaving a series of points of entry to Nirbhaya, a work whose narrative occasion might well mislead us to think we are being invited to mourn one truly appalling death in the city of Delhi in 2012, feeling horror at the extreme suffering and torture that preceded it. We might reduce the monument and its related sounds and video cantos to being elegies or laments for one death, or even the many deaths of which this one might become the symbol. Lamentation and the lament are indeed occasioned by death, destruction and loss. Art is, however, a transformation of the occasioning event into an aesthetic formulation that aims to act on its viewers and listeners on behalf of life over time. Lamentation at the graveside or before the funeral pyre is for the intimate mourners of the person who is now dead. An artwork produces a constant present of the now-encounters for each unknown person who comes to the site. It can become a ‘transport station of trauma’.

This is a crucial concept that I draw from the writings and artworking of the artist Bracha L. Ettinger about her own work but also many artists also confronting the legacies of history through art.

The place of art is for me the transport-station of trauma: a transport-station that, more than a place, is rather a space, which allows for certain occasions of occurrence and of encounter, and which will become the realization of what I call borderlinking and borderspacing in a matrixial trans-subjective space by way of experiencing with an object or process of creation. [24]

We do not encounter art in order to understand pure meaning. Instead, Ettinger proposes that contemporary art confronting the traumas of past and present becomes an occasion for an encounter with its traces, reformulated or materialized by the art that creates a space for encounter. The encounter works by means of an experiencing with what has been made, or as significantly, with the process of its making, with its materialities and temporalities as much as with the subjectivity and ethics of the artist. Working with is more than knowing how it was made. For in contemporary art that uses time for instance, or moving image, performance, drawing, sound, space, and installation, the artworking is constantly emerging in our engagement with the temporality and the materiality of the perpetual ‘becoming’ of the artwork. This is where and how the modernist interruption of the terms of Western European plastic representation, redirecting art to its own processes and their effects, leaves its permanent imprint, even as contemporary art emerged from its formalist, medium-based puritanism to reclaim apparently exiled content. The outcome of the encounter is, Ettinger explains, not predictable.

“The transport is expected in this station, and it is possible; but the transport-station does not promise that passage of remnants of trauma will actually take place in it. It only supplies the space for this occasion. The passage is expected but uncertain; the transport does not happen in each encounter and for every gazing subject. The matrixial tran- subjective field is a field in whose scope there is no point in speaking either of certainty or of absolute chance.” [25]

Ettinger opens the question of how art can engender a trans- subjective space ‘by way of experiencing with an object or a process of creation.’ This absolves the artwork from being a container of meaning, a narrator of events or a statement of intention. The emphasis moves away from classic oppositions: artist and viewer/spectator/reader to the space engendered in and as the encounter — artist with the world during her process of creation — and then to the space of encounter for the viewers as a place of wit(h)nessing (Bracha Ettinger’s term that combines witness and being with) whose affective charge and meaning depends upon the capacity of wit(h)ness (viewer or reader) to fragilize her/ himself so that the limit, frontier between subject and subject, subject and object, my experience and that of others, is transgressed and becomes a borderspace, a threshold for transmission.[26] Such a transmission and bearing of the trauma of other or world cannot be predicted or presumed since the transmission stems from one transubjective encounter-event that generated the art and relies on evoking another with the potential wit(h)ness (viewer/reader) whose frontiers are fragilized during the art encounter. [27]

For the condition of self-fragilization (her term), Ettinger formulated an entire theory of ‘the matrixial transubjective field’ that counters the conventional philosophical and psychological concepts of a discrete self (I) opposed to a discrete other (Not-I). I am not going to elaborate this theory fully here.[28] I introduce it not only to situate theoretically my own reading of Monika Weiss’ artworking but also to introduce the insights necessary for new kinds of reading of what artworks are doing when artists share the imperative to remain with the unacknowledged traumas and historically overlooked suffering that we need to process, and which new aesthetic modes enable us to encounter in order to do so. Ettinger explains a new kind of beauty that is neither aestheticization nor sublime:

“Beauty that I find in contemporary artworks that interest me, whose source is the trauma to which it also returns and appeals, is not ‘private’ beauty or that upon which a consensus of taste can be reached. It is a kind of encounter that, perhaps, we are trying to avoid much more than we are aspiring to meet, because the beautiful, as the poet Rilke says, is but the beginning of the horrible in which — in this dawning — we can hardly stand. We can hardly stand at the threshold of that horrible, at that threshold, which may be but, as Lacan puts it in his seventh seminar, the limit, the frontier of death — or should we say self-death? — in life where life glimpses death as if from its inside (Lacan 1986 [1959–60]). Could such a limit be experienced, via artworking, as a threshold and a passage to the Other? If so, is it only the death-frontier that is traversed here? Is death the only domain of the beyond?” [29]

[VI] THE ARCH AND THE SARCOPHAGUS

Is the vertical single arch architecture or is it an architectural figure of a body astride space like a new Colossus? What happens when the single arch is doubled and turned from its vertical axis to the horizontal? What is the effect of making a historical monument to war and power both a fluid font and an animated coffin? Do triumph and militarism yield to sorrow and mourning before a crime? Nirbhaya will deprive the India Gate of its history.

Monika Weiss has transformed the India Gate by doubling, mirroring, closing. She creates thereby a sarcophagus that will contain the traces of the images of many women who have joined Monika Weiss to perform their enactment of a perpetual living mourning, folding and re-arranging their dark garments. In earlier works, Monika Weiss has previously used the equally charged symbolic form of a baptismal font as the container for several performances using her body alone, one work evoking a kind of amniotic water (Ennoia, 2002) and another bathing the body in the black, sticky sullying fluidity of machine oil (Elytron — dusza i ciało to tylko dwa skrzydła, 2003).

In our era, there is a powerful imperative for the radical decolonization of our minds and our societies in the hope of protecting and sustaining the humanization of all notably those who are marked in any way as other to the self, other to collective selves of nation, culture, religion, ethnicity and class. The event that gave rise to this artwork titled Nirbhaya took place in time, in 2012, in India’s political capital, a once medieval city rebuilt and renamed as New Delhi. It also belongs in monumental time, in the longer cultural era and symbolic system we term patriarchy. [30]

Nirbhaya is the coded name given to the Indian woman whose anonymity was protected by Indian criminal code because she was the mortal victim of a heinous crime that took place on 16 December 2012. The name of the physiotherapy student who died thirteen days later from her horrific injuries on 29 December 2012, Jyoti Singh, was revealed by her mother, Asha Singh in 2015 because she wanted her daughter to have her name, a name unshamed by the crime of which she was a victim. Nirbhaya translates as she, fearless or rather, fearlessness ‘in the feminine’. Jyoti Singh clung to life, only able to deliver her witness testimony by hand gestures and movements of her head before succumbing to internal damage so dreadful that no surgery could save her.

As this monument is installed in Poland, and as the associated forms and potential replicas of the monument travel to other sites, the question of specificity and transmission become political. Who can mourn whom? Who can remember whom? Who is inspired or even compelled to make a work to call upon the many, far from this young woman’s home and short life to meditate upon her in the forms made by this artist from another time and place?

[VII] MONUMENTS OF LOVE OR VIOLENCE

Let me situate myself. I was invited to New Delhi in 2011 to spend one month as the Getty Visiting Professor of Art History in the School of Art and Aesthetics of the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). It was my first visit to India, although through family histories there has been a long connection. Not arriving as a tourist but as the guest of an academic institution, I was provided with wonderful support in terms of having a car and a driver arranged to transport me when my hosts themselves did not take me around. I did not have to negotiate the streets alone. My main host, Professor Kavita Singh and her community of graduate students were specialists in the art and culture of the Mughal Empire that dominated the subcontinent from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, and was ended only in 1858 when the British Crown took over the subcontinental territories hitherto controlled by the commercial East India Company and formed the British Raj [Empire] — formally designating Queen Victoria Empress of India in 1876 — from which India won its independence after a ninety-year struggle for freedom in 1947.

Professor Kavita Singh wanted to prepare me carefully for the inevitable journey I would make during my stay to Agra to encounter the Taj Mahal, by introducing me to several Mughal monuments in the city of Delhi so as to understand the evolution of their architectural styles and the symbolic meaning of their funerary forms. The Taj Mahal was commissioned in 1632 by Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan (reigned 1628–1658) and completed finally in 1653. It represents the major monument in terms of its shift from the Mughal aesthetic of red stone to the use of white, inlaid marble.

The Taj Mahal is relevant to the work of Monika Weiss because this most famous monument of Mughal India — and perhaps iconically representing India to the world — was itself a tomb, a monument built out of grief for the Emperor’s beloved wife, Mumtaz Mahal, who had died in childbirth in 1631. I want to link this funerary monument to love to my analysis of the memorial monument and space by Monika Weiss, dedicated to a young Indian woman who died prematurely but in grievous circumstances that captured the imagination of the entire world for a moment in 2012–2013. Monika Weiss’ gesture and the aesthetics of her artwork, calling upon us to remember Jyoti Singh, do not signify a singular sexual love, as in the historical case of the Taj Mahal. Her project seeks to incite in us, the many and from wheresoever, an equally intense compassion that we must feel if we are to preserve the humanity and singularity of all women in the face of crimes against women.

During my last days of the work at JNU, my host colleagues realized I had not really been taken to the main tourist sites of Delhi itself. Many of these are the monuments built by and for the British Empire, which, in almost Roman terms, laid its monumental hand upon the capital city of colonized India in massive stone writing. I was, therefore, taken to see the also iconic India Gate, itself a memorial shrine to the dead — but through war and conquest. The India Gate is a Triumphal Arch modelled on the Roman prototype. The India Gate is a descendants of Rome’s triumphal arches such as the Arch of Titus (ca. 81 CE) that has been the inspiration for The Arc de Triomphe in Paris, the Wellington Arch in London, the Arcul de Triopf in Bucharest as much as the India Gate in Delhi.

Sliding down a chain of associations of memorial gates and tombs, I recalled my own visit to the Belgian town of Ypres at whose Menin Gate the Last Post has been mournfully and faithfully sounded every evening since 1928, when it was built to mark the tenth anniversary of the ending of World War I in 1918. In the mausoleum within this version of Titus’s Triumphal Arch, officially the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing, are engraved the names of those World War I soldiers known to have been lost to history, and who thus have no graves, even marked by the anonymous phrase, reserved for unidentified human remains recovered from the Belgian battlefields: ‘Known only to God’. On the Menin Gate 54,395 inscribed names register the men of many nations who fought in the battles for Ypres associated with the name Passchendaele Ridge: from Australia, Canada, the Indian subcontinent, South Africa and the United Kingdom. Over 200,000 men from these countries were killed in the Ypres Salient. These names memorialize the colonial and imperial reach of the European Expeditionary Forces, which included many soldiers from the Indian subcontinent. The inscription by Rudyard Kipling reads:

To the Armies of the British Empire who stood here from 1914 to 1918 and to those of their dead who have no known grave.

The India Gate [fig. 12] in Delhi was also built as such an imperial war memorial. Its building was commissioned by the Imperial War Graves Commission, founded by Sir Fabian Ware in 1917. Its full title is All India War Memorial. It commemorates over 70,000 Indian troops of the British Indian Army. 13,300 names are inscribed.

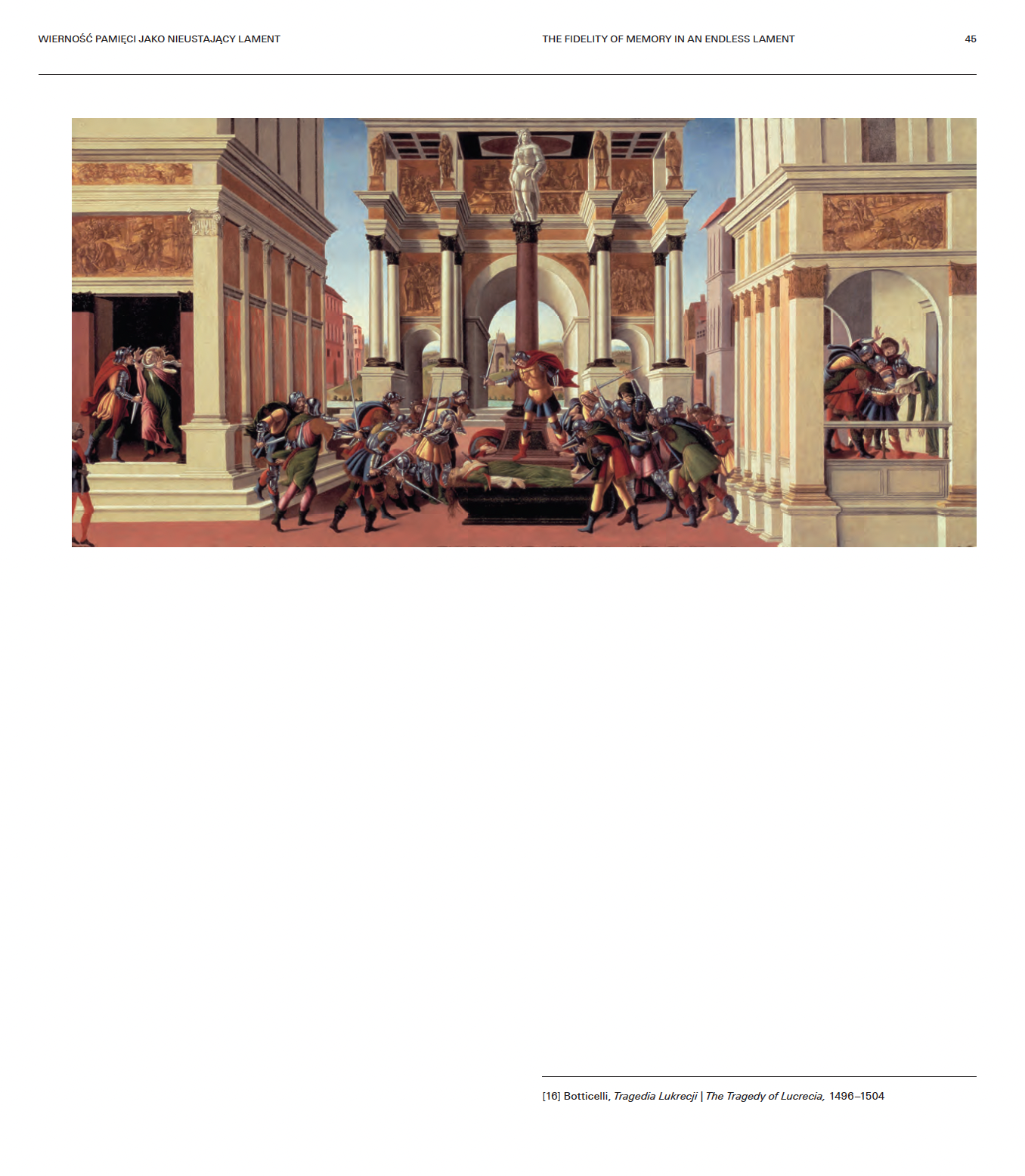

Let me reconnect with my virtual museum, and this collection of triumphal memorial arches and introduce the cassone painting, The Tragedy of Lucretia by Florentine painter Sandro Botticelli, painted between 1496 and now in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston [fig.16]. It connects the triumphal arch to a story of rape. The complex composition is composed of three scenes, two smaller ones flanking the central space; itself dominated by the triple arch of Constantine (Rome, 312 CE). The flanking scenes portray, on the left the rape of the Roman matron, Lucretia by Sextus Tarquinius, the son of the last King of Rome, and on the right, her suicide committed to erase the shame of the unwitnessed crime against her.

The central image places the dead Lucretia on top of a black marble sarcophagus surrounded by highly agitated and dynamic figures of men in armour, lamenting the dead woman in a variety of classic gestures: hands raised, faces covered, heads held in their hands, bodies bowed, mouths open in howls of grief. Towering above them on a column is a sculptural group of David with the decapitated head of Goliath, David being the symbol of the city of Florence (not the Rome of this story). This scene represents the mythic narrative of the foundation of the Roman Republic. Dominating the scene is a triumphal arch, the stage for this drama in three acts.

I introduce Botticelli’s painting work into my discussion of the installation Nirbhaya by Monika Weiss for three reasons. I was struck by the curious coincidence of three elements, the triumphal arch, the horizontal sarcophagus exposing the body of a raped, and now dead woman, and the proliferation of energetic gestures and poses signifying the intense emotions and expressions of horror and grief.[31] Botticelli’s imaginary Rome might speak across the centuries to a contemporary artist’s equally powerful evocation of a great city, Delhi, capital of a republic, India, founded also in a revolt against the weight of an imperial rule written into its architecture in the form of the India Gate.

The India Gate was the place where the crowds gathered in December 2012 and later to make their public protest after the crime whose victim was been named Nirbhaya and to protest against the dangers Indian, and all, women face, not from war, but in daily life in our cities and homes. Weiss has taken over its single-arched form. By doubling the arch and laying it down, the artist created an enclosed form, akin to a sarcophagus. Her now horizontal container that will become a monument will not, however, expose a brutalized body. It will become the open space that will solicit a prolonged meditative gaze as the projected, moving images of many women whose own black-clothed bodies and morphing hand gestures will ritually and hypnotically perform a slow dance of mourning gestures on their perpetually horizontal axis and in an unmoored space of unstill, originary and symbolic water.

[VIII] THE CRIME

What art can speak to an event that is not exceptional, except in its ferocity and horror and deadly outcome? At the heart of Monika’ Weiss’ work is one historical event that is, however, in all the grief for one woman it inspires, terrifyingly indicative of a murderous crime that is never memorialized. Let me start with some important clarifications of the crime against which Monika Weiss’ Nirbhaya project solicits our lamentation.

Rape is the systemic foundation of hierarchy based on gender in the patriarchal imagination

Rape is a murder of a self (Mieke Bal).[32]

Rape is crime of violence spoken through a body and to a body.

Rape is a crime of patriarchal violence against woman: it produces, sustains, and polices patriarchy’s concept of ‘woman’.

Rape is not widely practised in the animal world even up to our nearest relatives among the great primates. As a singularly human, social phenomenon, rape has, as Susan Brownmiller revealed in a landmark feminist publication in 1975, Against Our Will, become a systematic, militarized, criminal and punitive practice with real and continuing if not deadly effects for human society, and is all pervasive, being celebrated in both popular culture and its narratives. [33]

Used in war as an instrument of terrorization and demoralization, occurring on our streets and in our colleges and homes, we must understand it not as an aberrant crime of deviant individuals: bad men versus good men. Rape, real and threatened, is, as Brownmiller reveals in stunning detail and current protest movements by women, the systemic foundation of hierarchy based on gender in the patriarchal imagination. It translates into the gender divisions of social space and dangers for women in public space, into the gendered differentials of vulnerability, mobility, safety and access to education and personal freedom from harassment in and access to employment.

Rape is also, Mieke Bal argues, a speech act. [34] It is spoken through the body of another. Rape uses the sexual body to perform a crime of both physical violence and psychological violation. Rape is not always also a physical murder. Always, however, it is, Bal argues, the murder of a self, a crime that leaves its victim-subject alive to live with the internal, and psychological, impact of her own effacement by an other’s — the perpetrator’s — hatred and acted out disgust.

Western literature (Ovid, for example) and European visual art (notably in Renaissance and Early Modern periods) have, as I have shown, aesthetically accommodated our imaginations to rape as a language as much as to an event that founds societies or cultural systems. This culture must be described, as cultural analyst Mieke Bal and classical scholar Victoria Rimmel have argued, endemically rapish. [35]

Despite the regularly horrifying statistics of rape worldwide — and given that we are told that over 90% of rapes are never reported let alone prosecuted, — the crime perpetrated on the night of 16 December 2012 in Munirka, South Delhi, India, namely the gang rape and torture by six men of a young woman student on a private bus when she was on her way home around 9pm from seeing The Life or Pi with a male friend, shocked the entire world. Every element revolted us. Neither tears of grief nor howling rage could assuage the horror. In the city of Delhi, massive crowds gathered at police stations, initially to protest their despair at the failures of the policing of the city and their consistent ineffectiveness in catching and prosecuting criminals. Then, the crowds gathering at the India Gate to express horror and distress at what had happened to the woman, subsequently known in the press by the pseudonym Nirbhaya, and, through her singular tragedy, to denounce all such violence against women. They also wanted to protest against the daily sexual harassment of women in India in the streets and on public transport where they endure perpetual exposure to men’s ogling and indecent, often sexual touching of their bodies in public space as they travel to work or study. [36]

Jyoti Singh, Nirbhaya, died from her internal injuries after thirteen days of agony on 29 December. Hence she was also murdered. Six men were arrested within six days in an intense police hunt. Five were convicted and sentenced to death by hanging. The gang leader died, or was possibly killed, in prison. One perpetrator was a juvenile and was not condemned to death. Appeals against the sentences of the other four continued for years. They were finally executed in March 2020.

As a result of the massive world coverage of the crime and the continuing protests against violence against women and the publicly expressed demands for the safety of women in public places in India, filmmakers outside India have engaged in both documentary and fiction forms with both the specific crime and the conditions in Indian society from which these perpetrators emerged. Thus, the event was the topic of a BBC documentary India’s Daughter (2015) directed by filmmaker and human rights activist Leslee Udwin, released to coincide with International Women’s Day 2015 and to function as a general protest against violence against women.

Sociology and psychology were the basis for Indian-Canadian director Deepa Mehta’s Anatomy of Violence (2016) which used improvisational techniques with her six men-actors to examine the deep social roots of the crime in poverty, the caste system, limited education, inequality, and child abuse in India. Turned into a police procedural in seven episodes, the Netflix series Delhi Crime in 2018 (created by Richie Mehta) focused on the six days of the dedicated police search for the perpetrators, set against the massive protests and the Indian government’s violent reaction to the people’s distrust. Its central dramatic structure was built around the relations between three women: Jyoti Singh, Chhaya Sharma, the woman Deputy Commissioner of Police who led the investigation and her young woman constable (Neeti Singh is the character’s name) on her first assignment. Centering the story in this way, without showing the event, the other characters became mouthpieces for the variety of viewpoints of people struggling with the psychological and sociological analyses of not only the six perpetrators them- selves but also the conditions in contemporary Indian society that made such crimes possible.

I have named these forms of contemporary engagement with the event of 16 December 2012 in Delhi with respect. We must indeed remember and use our shock to remember every minute, every other violation of women. These facts bookend my attempt to introduce and write about Monika Weiss so as to situate the work that her elaborate, complex, multi-part project as itself a durational event aims to perform in perpetuity. Although inspired by the artistic form of the counter-monument, Monika Weiss’ artwork is what I suggest can be named a counter-event that does not dramatize violence, either of the crime or of the protest. It exiles from the visitor’s experience both context and perpetration. It links the thoughts and affect that will continue to unfold for each and every visitor in this park in Poland to Nirbhaya, by title — the name of she, the fearless, — and by means of our contemplation of the water-filled sarcophagus that doubles and closes around the bodies of women, the India Gate of Delhi.

It also does so through the haunting sound in our ears and through inviting us to gaze at the moving films of quiet gestures of soundless lament and at the materialized, monumental drawings of the fleeing Daphne, the perpetually escaping figure who became the upright pagan tree of returning life.

I suppose in that sense, the only term with which to acknowledge the scale and affective force of Monika Weiss’ project is monumental. Yet, her work is imbued with political and aesthetic sensibility deeply resistant to monumentality and its dangerous political histories. Monika Weiss’ fidelity to Nirbhaya seeks instead to touch and affect us through sound, movement, drawn and filmed bodies and space; so that we cannot but share and carry with us everywhere this memory, this pain, this desire for a different world.

Griselda Pollock, London, 2021

Notes:

[1] I refer here to Edgar Wind’s thesis about the difference of modern art from its preceding forms in Art and Anarchy, London: Faber & Faber, 1963.

[2] I have offered a series of readings, paranoid and reparative, of the statue of Daphne by the Italian Baroque sculptor, Bernini, as the opening chapter of my Afer-affects / After-Images: Trauma and Aeshetic Transformation (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013). Being raped, or being humanly dead were, in my view, the options of this mythical figuration of the feminine in the patriarchal symbolic and social order.

[3] I am thinking especially of site and event related work such as Sustenazo (2010) based on event in Warsaw in 1944 and Shrouds (2012–2013) based on a disregarded concentration camp site in Zielona Góra.

[4] Jane Harrison, Ancient Art and Ritual [1913]. Harrison was a feminist classicist and the first scholar to hypothesise the origins of art in rituals created by humans to negotiate the anxieties of life and death,

beginning and ending, birth and rebirth. Much appreciated by modernists Virginia Woolf and James Joyce, Harrison’s work was also read by Abstract Expressionist painters such as Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock.

[5] Saul Friedlander, ‘Introduction’, in Probing the Limits of Representation: Nazism and the “Final Solution”, Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 1992), pp. 1–21: 9.

[6] Eric Santner, ‘History beyond the Pleasure Principle: Some Thoughts on the Representation of Trauma,’ in Saul Friedlander (ed.), Probing the Limits of Representation: Nazism and the Final Solution, Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 1992, pp. 143–54: 144.

[7] James Young, At Memory’s Edge: After Images of the Holocaust in Contemporary Art and Architecture, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000, notably chapters on works by Jochen Gerz and Esther Shalev-Gerz, Horst Hoheisel, Shimon Attie, Rachel Whiteread.

[8] Walter Benjamin, ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’, in Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt and translated by Harry Zohn [1968], London: Fontana, 1977, pp. 255–267: 257.

[9] Griselda Pollock, Encounters in the Virtual Feminist Museum: Time, Space and Archive, London: Routledge, 2007. The term artworking has been created by the artist Bracha L. Ettinger in relation to her own post-traumatic aesthetic practice. Like dreamwork, the work of mourning and working through in Freudian psychoanalytical theory, artworking concerns the transformative work of art in relation to the wounds of the world. Bracha Lichtenberg Ettinger, Artworking 1985–1999 (Brussels; Palais des Beaux Arts and Gent Ludion, 2000) notably her essay, ‘Art as a Transport Station of Trauma’, pp. 91–116.

[10] In 1915 Freud radically altered his understanding of the psyche from a cathartic to an economic model. Psychological change is not an abreaction to one traumatic event. It involves work and transformation. Freud had already theorized dreaming as Traumarbeit, dreamwork. Facing the deaths and fear of death during World War I, he introduced Trauerarbeit, the work of mourning. He generalized this economic model for analysis itself as Durcharbeiten, working through. The artist Bracha Ettinger extended this model with her concept of artworking: art as the work of transformation. On my understanding of Ettinger’s key concept see Griselda Pollock, After-affects / After-Images: Trauma and Aesthetic Transformation in the Virtual Feminist Museum, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013.

[11] Joseph Winters, ‘Contemporary Sorrows Songs: Traces of Mourning, Lament and Vulnerability in Hip Hop’, African American Review, 46:1 (2013),

pp. 9–20: 9.

[12] Griselda Pollock, ‘Traumatic Encryption: The Sculptural Dissolutions of Alina Szapocznikow’, in After-affects / After-Images: Trauma and Aesthetic Transformation in the Virtual Feminist Museum, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013. Studying the trajectory of her sculptures, I noted the progress decline from an assertive verticality of the human figure into the infor me, the formless increasingly dissolving and slipping, situated more and more on the horizontal axis, and ultimately laid directly on the ground.

[13] Julia Kristeva, ‘Holbein’s Dead Christ’, in Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia, trans. Leon S Roudiez, New York: Columbia University Press, 1989, pp. 105–139. [Soleil Noir: Dépression et Mélancholie (Paris: Editions Gallimard, 1987)], p. 119.

[14] Kristeva 1989, pp. 113–114.

[15] Robert Graves, The White Goddess, London: Faber & Faber, 1948; Aby Warburg, Sandro Botticelli’s “Geburt der Venus” und “Frühling”: Eine Untersuchung über die Vorstellungen von der Antike in der Italienische Frührrenaissance’/ Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and Spring. An Examination of the Representations of Antiquity in the Early Italian Renaissance [1891] Printed in Hamburg and Leipzig: Leopold Voss, 1893. Catherine Clément and Julia Kristeva, Le féminin et le sacré, Paris: Stock, 1998; The Feminine and the Sacred, trans. Jane Mary Todd, New York: Columbia University Press, 2003.

[16] Linda M. Austin, ‘The Lament and the Rhetoric of the Sublime‘, Nineteenth- Century Literature, 53:3 (Dec., 1998), pp. 279–306: 280.

[17] Margaret Alexiou, The Ritual Lament in Greek Tradition, Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1974, p. 13; Austin 1998, p. 281. In Irish culture, however, there is a specific tradition called ‘keening’, the Gaelic word caoineadh meaning crying. Keening is a high-pitched, vocable but wordless ritual mourning practised by women (mnàthan-tuirim in Gaelic).

[18] Alexiou 1974, p. 13.

[19] Austin 1998, p. 281.

[20] Austin 1998, 283. See also https://chs.harvard.edu/CHS/article/display/ 6678.6-the-classification-of-ancient-and-modern-laments-and-songs-to-the-dead

[21] Austin 1998, p. 285.

[22] Austin 1998, p. 298.

[23] Austin 1998, p. 293; Jean-Luc Nancy, ‘The Sublime Offering’, in Of the Sublime: Presence in Question, essays by Jean-Francois Courtine, Michel Deguy, Eliane Escoubas, Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, Jean-Francois Lyotard, Louis Marin, Jean-Luc Nancy, and Jacob Rogozinski. Trans. Jeffrey S. Librett, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993, p. 53.

[24] Bracha L. Ettinger, ‘Art as the Transport Station of Trauma’, in Bracha Lichtenberg Ettinger Artworking 1985–1999, Brussels Musée des Beaux Arts and Gent: Ludion, 2000, pp. 91–115: 91.

[25] Ettinger 2000, p. 91.

[26] Wit(h)ness is an untranslatable English neologism created by Ettinger combining the legal concept of the witness, the other who was present to affirm a crime has occurred, with the concept of being with, remaining beside, standing with, sharing with the suffering other. It is the condition of ‘the impossibility of not sharing’ the suffering or dehumanization of the other.

[27] This is a term created by Bracha L. Ettinger, Fragilization and Resistance, Helsinki: Kaiku Gallery, Finnish Academy of Art, 2009, pp. 97–134.

[28] I have edited two volumes of this artist-theorist’s writings,

Bracha L. Ettinger, Matrixial Subjectivity, Aesthetics, Ethics (Vol 1 1990–2000; Vol 2 2001–2010, Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2020) which offer introductions to each text and a substantial introduction to each volume.

[29] Ettinger 2000, p. 91.

[30] Julia Kristeva, ‘Le Temps des Femmes’ [Cahiers de recherche de sciences des textes et document, 5, 1979, pp. 5–19]; ‘Women’s Time’, in Toril Moi, ed., The Kristeva Reader, Oxford: Blackwell’s, 1986, pp. 187–213. Kristeva reminded us of the difference between linear history, the time of nations and production, and monumental time, that deals with life, death, the body, sex and symbol, and reproduction.

[31] The critical element of the story of Lucretia, that appeared frequently in Renaissance and Baroque painting is the sequence of her rape and

her suicide. Having been raped in a crime that has no witnesses, Lucretia, the wife of a political leader, chose to kill herself to erase her ‘shame’.

This is explored narratively and semiotically in her brilliant studies of the Lucretia paintings by Rembrandt in Mieke Bal, ‘Visual Rhetoric: The Semiotics of Rape’, in Reading Rembrandt: Beyond the Word Image

Opposition, Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1991, pp. 60–93. I am deeply indebted to Mieke Bal’s profound work on this topic. I do not have time to elaborate her argument. I draw here on her argument that rape is always a murder, a murder of a self, and the Lucretia story is to be read not as pure narrative but as the installation of this inevitable connection even if the woman survives the crime.

[32] Mieke Bal, ‘Visual Rhetoric: The Semiotics of Rape’.

[33] Susan Brownmiller, Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape, London: Martin Secker & Warburg, 1975.

[34] Mieke Bal, ‘Visual Rhetoric: The Semiotics of Rape’.

[35] Victoria Rimmel, Ovid’s Lovers: Desire, Difference and the Poetic Imagination, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

[36] I was personally made intensely aware of the political issue of the aggressively masculinized public space in India by my academic colleagues at JNU who, for reasons of work, had to use public transport and felt vulnerable and humiliated by what they endured when travelling. Space is one of the key components of social hierarchy and of gender. Anthropologist Shirley Ardener argues: ‘Societies have generated their own culturally determined ground rules for making boundaries on the ground and have divided the social into spheres, levels and territories with invisible fences and platforms to be scaled by abstract ladders and crossed by intangible bridges with as much trepidation and exultation as on a plank over a raging torrent. Shirley Ardener, Women and Space, London: Croom Helm, 1981, pp. 11–12. Statements by the perpetrators of the crime against Jyoti Singh referred to her ‘misbehaviour’, being out late at night (21.00), touching in public, and not submitting to her ‘punishment’ but ‘fighting back’.

Griselda Pollock

Griselda Pollock is an art historian and cultural analyst of feminist, international, postcolonial, queer studies in the visual arts and visual cultures. Known for her theoretical and methodological innovations and interpretations of historical and contemporary art, film and cultural theory, Pollock has challenged her own discipline. Her book Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology, co-authored with Rozsika Parker (1981), just republished in 2020, is a still relevant and radical critique of art history and its gender-selective canon. It has become a classic text in feminist art history, as has her book, Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and Histories of Art. (1988) Developing transdisciplinary approaches to contemporary art and its new forms and media, she is recognized as a major influence in feminist theory, feminist art history and gender studies. In March 2020, Pollock was named as the 2020 Holberg Prize Laureate for her ground-breaking contributions to feminist art history and cultural studies. Griselda Pollock is now professor emerita at the University of Leeds where she taught for 43 years. She has published 22 monographs, with four more forthcoming. Her most recent monograph is Charlotte Salomon in the Theatre of Memory (Yale University Press, 2018). Griselda Pollock is the author of the main essay in the monograph Monika Weiss-Nirbhaya, published by the Centre for Polish Sculpture Press (2021).