katarzyna falęcka

Monika Weiss-Biography

by Katarzyna Falęcka

in Monika Weiss - Nirbhaya, Centre of Polish Sculpture in Orońsko, pp. 147 - 167, 2021

“Silence is not about absence of sound, but rather about quietness: the hush of early dawn, at the boundary of the world”[1] – Monika Weiss

Over the past twenty-five years, the Polish-American artist Monika Weiss (b. 1964) has developed an aesthetic vocabulary of profound emotional impact through which she explores the body, history and violence. Born in Warsaw, Poland, Weiss was trained as a classical pianist at the Warsaw School of Music before completing MFA at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts in 1989, where she was mentored by the conceptual artist Ryszard Winiarski. In the mid-to-late 1990s, she was awarded artistic residencies at Georgia State University and at The University of Maryland. These were followed by a long-term residency at the Experimental Intermedia Foundation in New York in the early 2000s, which resulted in Weiss’ permanent relocation to the United States and encouraged her to continue developing a practice that surpasses the limits of conventions around medium. The visual, the sonic and the haptic are all placed on a par in Weiss’ works, which reveal the deeply entangled nature of artistic forms. Moving between the poetic and the political, Weiss explores states of suspension and stillness that disrupt the flow of time and hold a transformative potential.

Beauty is mobilised as a source of ethics; as Weiss creates synesthetic, meditative works that are intimately engaged with processes of commemoration. The artist employs her own body or choreographs other subjects, particularly women, to navigate the aftermath of violence and sites of trauma. The gendered body does not only become a vehicle of expression, but forms a key site from which an affective politics may emerge, through touch, vulnerability and the visceral. Weiss composes the sound that constitutes many of her works, considering the vocal-musical-poetic form of lament as a modality of collective remembrance that allows to articulate traumas without enacting further violence. By attending to events and histories that she has not personally witnessed, the artist unveils the multidirectional character of memory and seeks to forge new feminist solidarities that exceed national boundaries.

States of Becoming

Since the 1990s, Weiss has persistently composed an aesthetic vocabulary that has evolved throughout her practice. The body forms perhaps one of its most significant elements, becoming both a site of inquiry and an instrument of expression. Weiss’ early work Koiman (1998), inspired by two visions of Saint Catherine of Siena, revealed the artist’s understanding of the body as inherently porous. The artist drew on the story of the Catholic saint who, upon encountering a woman dying from breast cancer, is said to have drunk the black liquid flowing from her open wound. She would later repeat the same act by drinking blood from Christ’s suffering body. Weiss made a reference to these gestures by building a cast-concrete baptismal font and filling it with murky motor oil that would constantly overflow the vessel. The stream would move across the gallery floor towards a video projection that pictured an androgynous figure sucking at the breast of another. Composed of sculpture, video and sound, Koiman formed a multi-sensory environment, not least due to the repelling odour of motor oil that evoked bodily fluids and the slow decay of the woman’s body. Drawing on the psychoanalytic concept of the ‘abject’ defined by Julia Kristeva as that which provokes repulsion and threatens the integrity of the ‘self’ [2], Weiss explored the body’s liminal boundaries and its fragile relationship to culture. Koiman foreshadowed Weiss’ broader approach to the body which is cast in a continuous process of becoming throughout the artist’s practice, underscored by the frequent presence of a sculpture resembling a baptismal font.

For Weiss, baptism is a malleable metaphor, a state of passage that is further defined by a distinct physicality. Following a visit to the Cathedral in the Polish city of Wrocław where the artist noted a large-size medieval baptismal font for adults, Weiss began to stage immersions in octagonal vessels which she sculpted. In Ennoia (2002), the artist lied curled-up in a foetal position inside a water-filled vessel reminiscent of a baptismal font, occasionally moving along its inner walls, only to immerse herself again. During the six-hour-long performance, underwater microphones installed in the basin picked up sounds of immersions, amplifying the physicality of this symbolic act of initiation, rebirth or cleansing. [3] The embryo-like position adopted by Weiss refigured the vessel as a maternal womb that contains a vulnerable body, not yet inscribed by social processes that seek to align it with cultural representations.

Weiss frequently amplifies the tension between the embodied self and its visual representation by including video projections of her performances, filmed either in real time or appearing in a version edited by the artist. Ennoia too included a camera hung from the ceiling, turning the physical presence of the artist in the gallery into an immaterial, flat image that disrupts the intimacy and solitary character of her gestures. ‘My body is both a container and an object contained’ [4], Weiss has evocatively noted, dramatising the persistent struggle of how our bodies come to be inscribed with social, cultural and political meanings. Questions of subjecthood sit at the core of Weiss’ practice as she explores the sensory and psychic realm in which the body manifests its own energy against constraints and prohibitions.

While Weiss frequently works with her own body or choreographs others, she also absents the physical body, choosing to explore its refracted image instead. For White Chalice (Ennoia) (2004) [illustration I], Weiss projected a video documentation of her repeated immersions and curled-up body onto the water that filled a five-foot tall octagonal fiberglass chalice, creating a ghostly reinhabitation. Sounds of whispered words and splashing water could be heard as visitors approached the vessel, their own shadows reflected in the water’s mirroring surface. Water is a recurring material in Weiss’ practice due to its relational nature as it holds the refracted reflections of its surroundings, tentatively separating the interior and exterior. The artist’s sculpted, water-filled baptismal fonts speak to American artist Roni Horn’s translucent metal and cast-glass pools of water that act as metaphors of fluidity, performativity and androgyny. Likewise, for Weiss, water undoes the culturally-imposed boundaries of the body, returning it to its pre-natal state in which the self, the corporeal and language are all in a state of continuous becoming.

Beyond Language

Weiss’ large-scale, charcoal drawings further trace the body’s struggle to remain within its designated contours. In Kordyan (2005), Leukos 2 (2007) and Sustenazo (2009–2010), charcoal acts like water, blurring the outlines of curled-up or stretched out bodies that appear as dark silhouettes [illustration II]. Mark McDonald, Curator of Prints and Drawings at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, has noted the elusive appearance of the body in these works. ‘Weiss’ drawing’, he wrote, ‘oscillates between proposal and presence, the allusive and the tangible’ [5].

For Weiss, drawing is less a process of deliberate mark-making than an intuitive, emotional and sensorial act. For Lethe Room (2004), the artist sculpted a vessel reminiscent of a rectangular sarcophagus that was filled with layers of paper upon which the artist laid down. Holding chunks of graphite, Weiss slowly made marks on the papers’ delicate surfaces, leaving traces of her presence that was further eerily amplified when the paper began to move after the artist had left. Weiss translated a fragment of a composition by the twelfth-century composer Hildegard von Bingen into a mathematical system that would set the motor and sensors installed in the vessel in motion in a rhythm resembling breathing. The work forged a poetic connection that attempted to fuse the sounds and rhythms of the body with the physicality of drawing. The Indian poet Meena Alexander noted in relation to Weiss’ practice that it is marked by ‘a meditative embodiment of what lines or images cannot spell out: the impalpable’ [6], a quality that structures works like Lethe Room.

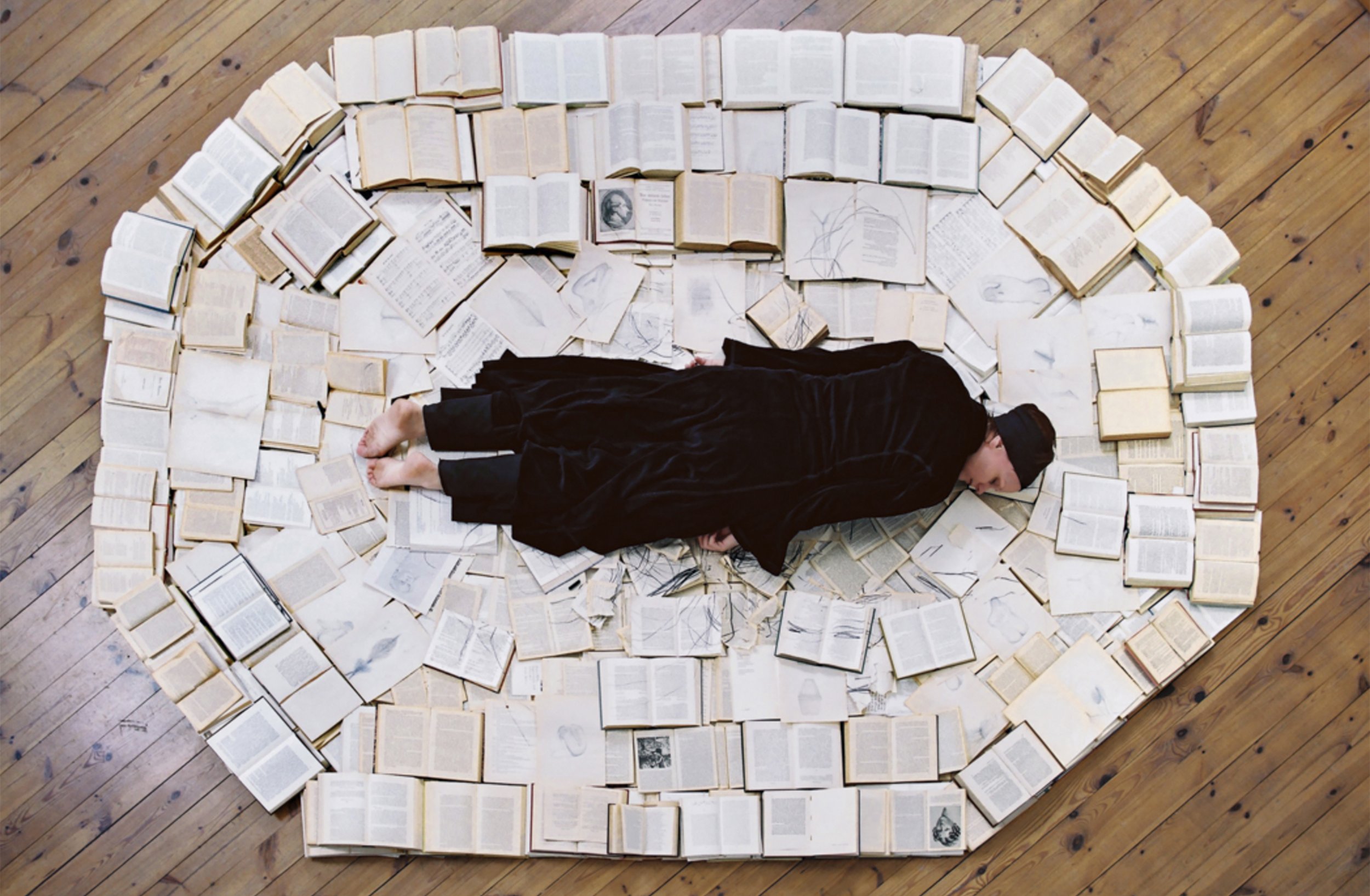

Weiss’ embodied practice foregrounds the sensorial as a modality through which we can develop an ethics and politics of remembrance and of being in the world, simultaneously challenging modernist assumptions concerning the duality of mind and body. Many of Weiss’ works include performative actions in which the artist keeps her eyes closed for several hours, delinking from the over-emphasis on vision as the primary sense structuring aesthetic experience and as a vehicle of secular reason, cemented by European Enlightenment. Phlegethon-Milczenie (2005), for instance, consisted of a bed of open books published in pre-war Germany on which the artist laid down, dressed in black and with her eyes closed. She then drew around her prostrate body with charcoal.

The slow mark-making, unguided by vision or any deliberate choices, allowed for an affective engagement with a cultural heritage that became enmeshed within the violent ideologies of the Nazi regime that either appropriated certain publications to foster its own views on what constitutes a ‘pure’ national culture or burned works that it considered to pose a threat to that notion. Weiss’ slow gestures inscribed the literary works with material traces that were neither representation, nor language, acting nonetheless in refusal of submitting cultural heritage to man-made, oppressive classification systems. The violence of this history was evoked through sounds of a burning book which the artist mixed with a polyphony of voices reading pages from selected publications, as well as with the voice of the countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo. [7] They formed a choir, creating a space in which literary heritage could be reclaimed. Like in Ennoia and several other works, Weiss projected a video based on her performance, filmed from above, in the adjoining room, dramatising the tension between the body’s sensorial being in the world and its visual representation. [illustration III]

Phlegethon-Milczenie has in many ways revealed Weiss’ approach to history that is less concerned with articulating distinct narratives or counter-discourses, than with exploring how the past is inscribed within the body and how the latter can in turn mediate traumatic histories. The prostrate body forms an integral element of Weiss’ artistic language, having evolved into a metaphor of horizontality, slowness and smallness. Weiss’ engagement with the horizontal body situates her within a longer genealogy of feminist practices such as the work of the Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta who adopted the act of laying down as an affective way of inhabiting the world. For Weiss, laying down forms an ‘ethical stance’, connoting earth, landscape, as well as submitting to the environment and refusing to dominate a site, all the while embracing the fear of death. [8]

Weiss has adopted this profoundly powerful metaphor of horizontality in works including Drawing Lethe (2006) where she inhabited a large cotton canvas spanned on the floor of the World Financial Center Winter Garden and moved silently within its boundaries, making charcoal marks around her prostrate body. Commissioned by The Drawing Center, New York, Drawing Lethe revealed Weiss’ concern for what she has called ‘states of regression from image and coded sign to states of pre-sign’,[9] in which both representation and language are at threat of collapsing. Drawing Lethe took place in the vicinity of Ground Zero where workers were still searching for remains five years after the events of 9/11. Joined by passers-by, Weiss mapped a wounded site within the body of the city and offered a way of working through loss that moved beyond a verbal articulation of pain. Like in Phlegethon-Milczenie, Weiss foregrounded drawing, sound, ephemeral presence and the bodily trace as modalities through which to approach trauma. For Weiss, an engagement with trauma often begins with a slow, intimate and sensorial encounter with a site or landscape.

A concern for how to make present traumatic histories without resorting to the shock of direct representation drives much of Weiss’ later practice after 2005, which also reflects a shift from solitary performative gestures to a choreographed engagement with others. Tracing the relations between performers over time and space, the artist suggests embodied ways of engaging with public memory, cultural amnesia and histories of violence.

Forging Solidarities through Lament

Weiss’ attention to expressive modalities that eclipse language has encouraged her to explore lament, an archaic form of music and poetry. Her practice refers to collective forms of lamentation traditionally performed by women as a symbolic resistance to the widespread suffering caused by war. For Weiss, lamentation forms both an immediate expression of collective memory and a unique vocal-musical-poetic form, which she marshals to navigate histories of violence. In Sustenazo (2010), the artist responded to the forced expulsion of patients and medical staff from the Ujazdowski Hospital in Warsaw, Poland, now a contemporary art centre, by the German Army in 1944.

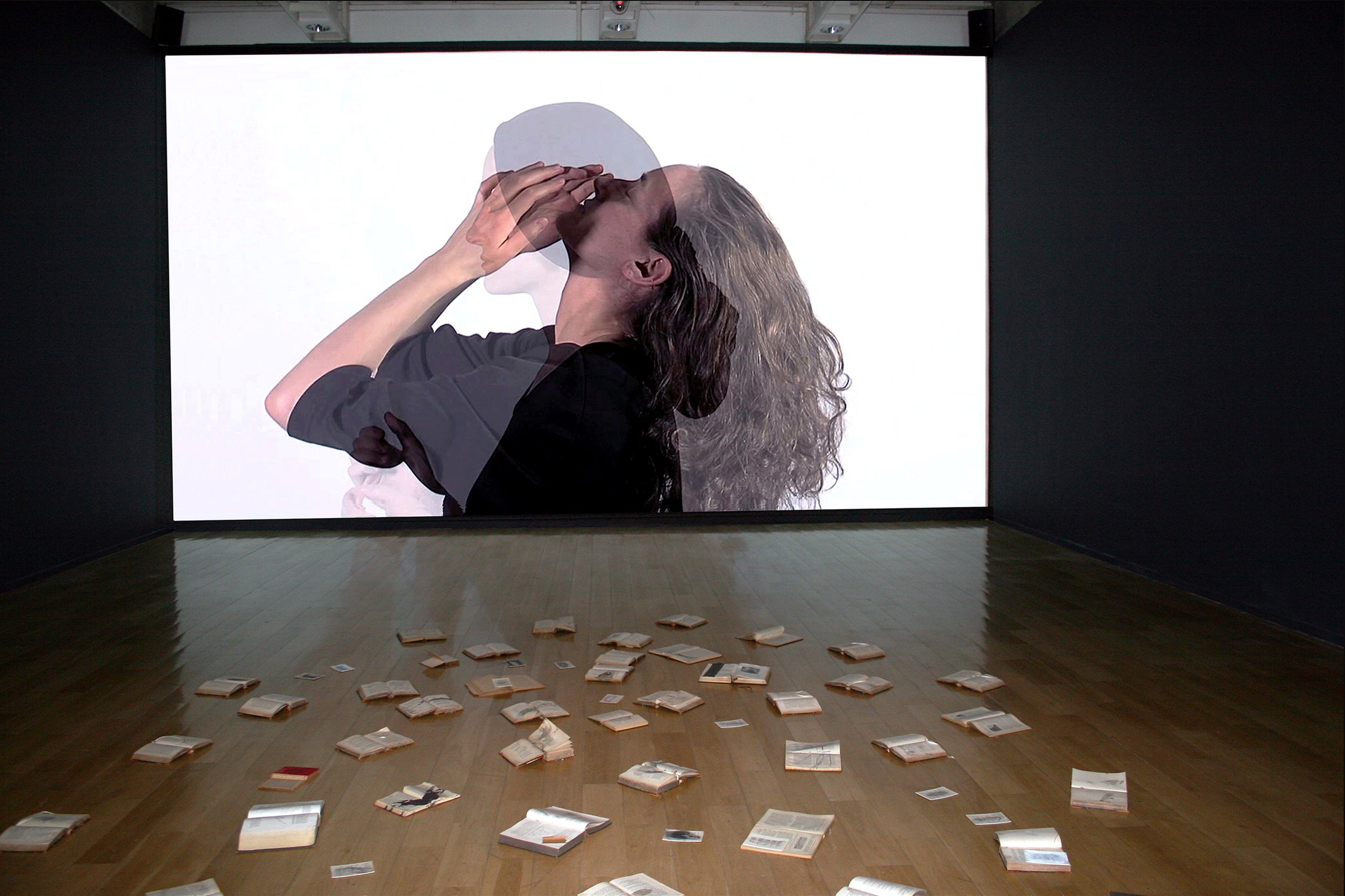

The site-specific intervention included a video titled Sustenazo (Lament II) that opened with two superimposed views of a female performer moving slowly backward and forward, her eyes closed. Her gestures embodied the timeless expression of lament. Weiss employed digital editing to ‘double’ the female body, building upon her earlier artistic inquiries into the ever-shifting boundaries of the ‘self’’. Lament II, however, opened up a new terrain of ethical inquiry that focuses on the relationship between the ‘self’ and the ‘other’ in processes of remembrance. Resisting the articulation of direct narratives in her work, Weiss intertwined the oral recollections of a Polish woman survivor of the expulsion, alongside recitations of passages from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, a writer revered by the Nazi regime, narrated by German speakers, and fragments of laments performed by Anthony Roth Costanzo. The process of composing included the use of digital programs with which the artist transformed previously recorded words and musical phrases, creating a new multi-layered sound composition that turned words and melodies into a unified, cacophonic lament.

Sustenazo (Lament II) juxtaposed the archaic form of lament with documents drawn from the archive of a historical event, including a German map of Eastern Europe from the war and pre-1945 medical books. While Weiss’ works are often triggered by specific histories of violence, the artist is equally concerned with mapping transregional landscapes of trauma. The exhibition Sustenazo (Lament II), for instance, was shown at the Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Chile [illustration IV], transgressing its original site-specific context. ‘By making the moving bodies of women, often including her own, a mobile alphabet of pathos’, Griselda Pollock wrote, ‘her [Weiss’] art speaks against violence at levels that reach back to the most archaic origins of ritual confrontations with life and death, terror and pathos’. [10] While lament stems from folkloric forms of expression, poetry and classical music, Weiss’ work can also be situated in relation to earlier feminist and artistic engagements with collective forms of mourning such as Suzanne Lacy’s and Leslie Labowitz’s participatory performance In Mourning and In Rage (1977). Here the artists mobilised the public ritual of grief in order to protest the media’s spectacular accounts of violence against women in Los Angeles. We can also consider Weiss’ practice in relation to the history of dance, specifically Martha Graham’s choreography of lamentation. [11]

Public projects that take the form of ephemeral and site-specific environments constitute an important strand in Weiss’ practice. In Shrouds-Całuny (2012), Weiss choreographed and filmed from an airplane, local women performing silent gestures of lamentation on the abandoned site of the former German concentration camp for Jewish women in what is now Zielona Góra, Poland. The volunteers would leave black scarfs on the ruins of the camp, marking the absence of the women who died in those ruins. Activating abandoned and forgotten sites of trauma, Weiss’ practice can be compared to the work of Doris Salcedo, who considers material objects as memory carriers and signifiers of violence. Shrouds-Całuny, like Sustenazo, attended to a site of ‘postmemory’ defined by the scholar Marianne Hirsch as the residue of historical trauma within the contemporary moment. [12] Shrouds-Całuny further explored the relationship between the body envisioned as a site of memory, pain, empathy and the camera’s mapping of space from an aerial perspective that eclipses lived experience. As such, it built on Weiss’ early interest in the tension between embodied presence and its filmic representation.

The rupture between the aerial, flat view of a city and the embodied experiences of women in public spaces structures Weiss’ video Wrath (2015), which simultaneously marks a shift from the artist’s focus on the traumatic histories of the Second World War to the more recent past. Opening with a view of Tehran that is overlaid with the shadow of a young Iranian woman architect, Wrath traces the vulnerability of the female body in urban spaces. The artist has continued addressing this concern in Two Laments (19 Cantos) (2015–2020), a series of nineteen films, and in the ongoing project Nirbhaya begun in 2015. These works are structured through an overlaying of images and voices of different women. In Wrath, a silent Iranian woman performs gestures of lamentation while another female voice slowly recites verses in Farsi, written by the artist, that poetically reflect the tension between urban spaces and women’s bodies. Then, her figure becomes obscured (through the use of montage) by layers of wavy black and white material that separate her from the viewer's gaze. For Weiss, the cloth serves a protective function. ‘Moments of historical and personal trauma’, the artist writes, ‘are best represented by veiling them into dignified, protected, and anonymous stories’. [13] Wrath is further imbued with great solemnity through Weiss’ piano composition, as well as her choreography that slows down the performer’s gestures to near stillness.

Weiss pursues the audiovisual poetics of lament in Two Laments (19 Cantos) which refigure collective grief as a powerful political tool. Each projection shows a female performer who is seen making gestures of lamentation, inhabiting a circular vessel in a protective, embryo-like pose or laying upon a historical etching of Old Delhi. Several of the videos include music composed by the artist, or recitations of her text performed in Sanskrit, Hindi, Bengali and Oriya, the ‘minor’ tongues of India. The words evoke the voice of Jyoti Singh (called “Nirbhaya”, the fearless), a young woman who was brutally raped and tortured on a moving bus in New Delhi in 2012 and who died from her injuries. With regard to this act of violence, which has provoked global outrage, 19 Laments by Monika Weiss indicts the selective politics of remembrance and points to the near absence of monuments dedicated to women. [illustration V]

Weiss’ first permanent outdoor project Nirbhaya, a monument to victims of gender-based violence named after Singh, is built through recurring elements of the artist’s aesthetic vocabulary. A water-filled vessel holds a video projection of a female figure dressed in black robes who morphs into the bodies of multiple women performing slow gestures of lamentation. She then morphs into a tree trunk, a transformation that is underscored by Weiss’ sound composition based on her piano improvisations. The slow, almost sparse melodies are evocative of the sounds of nature: the hollow sounds of a forest, howling wind or drops of water. For the sarcophagus-like vessel, Weiss doubled the shape of India Gate, an arch-shaped colonial monument built by the British in Delhi, placing it on the ground to undo the heroic verticality of public forms of commemoration.

The water and Weiss’ montage of the recorded footage perform the work of an eternal mirroring, overlaying the morphing female figure with the shadows of viewers in a gesture that refuses closure and a sublimation of memory. This multiplication of bodies allows for an intersubjective relation to emerge, activating what Kalliopi Minioudaki has called ‘audiovisual temporal sites of transcultural and transhistorical grief that, unmoored from their site-specificity, can resonate everywhere’ .[14] The currently considered future installment of Nirbhaya at Dag Hammarskjold Plaza – a gateway to the United Nations in New York City – for a six-month period, fleshes out the global resonance of Monika Weiss’ profoundly affective art practice that seeks to reimagine the world from an intersectional feminist perspective. [15] [illustration VI]

Katarzyna Falęcka, London, 2021

Notes:

[1] William Anastasi and Monika Weiss, ‘Baptism of Water: Conversation on Ennoia’, in Monika Weiss: Vessels, ed. Dina Helal, Chelsea Art Museum, New York, March 20-April 17, 2004, pp. 14–19, p. 18.

[2] See Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

[3] The sound for Ennoia (2002) was made in collaboration with the sound artist Stephen Vitiello.

[4] William Anastasi and Monika Weiss, ‘Baptism of Water: Conversation on Ennoia’, in Monika Weiss: Vessels, ed. Dina Helal, exhibition catalogue, Chelsea Art Museum, New York, 20 March – 17 April 2004, p. 15.

[5] Mark McDonald, ‘Drawing Consciousness: Monika Weiss’, in Nirbhaya, ed. Halina Gajewska, Orońsko: Centrum Rzeźby Polskiej, 2021.

[6] ‘Two Laments: Meena Alexander & Monika Weiss in Conversation. Moderated by Buzz Spector’, in Nirbhaya, ed. Halina Gajewska, Orońsko: Centrum Rzeźby Polskiej, 2021.

[7] The opera singer Anthony Roth Constanzo participated in Weiss’ multiple works, including Rivers of Lamentation (2005).

[8] Live interview with Monika Weiss by Nathalie Angles, Chelsea Art Museum, New York, 8 April 2004. See transcript at http://www.monika-weiss.com/articles/texts/130

[9] Monika Weiss, ‘Anamnesis (Światło Dnia)’, TA, 4:2 (2006), pp. 79–87, p. 79.

[10] Griselda Pollock, ‘The Fidelity of Memory in an Endless Lament. Nirbhaya, New Delhi, 2012, and now…’, in Nirbhaya, ed. Halina Gajewska, Orońsko: Centrum Rzeźby Polskiej, 2021.

[11] The American dancer and choreographer Martha Graham performed Lamentation in 1930 to Zoltán Kodály’s 1910 Piano Piece, Op. 3, No. 2. It became one of her signature works.

[12] See Marianne Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust, New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

[13] Monika Weiss, ‘Notes on Wrath’ (2015). See http://www.monika-weiss.com/articles/studio_writings/243

[14] Kalliopi Minioudaki, ‘Nirbhaya(s)’s Double Lament in Unforgetting and Protest’, in Nirbhaya, op. cit., pp. 95-108.

[15] Weiss’ public project Nirbhaya is scheduled to open in October 2023 at Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, United Nations, New York where it will remain on view until May 2024.

Dr Katarzyna Falęcka is an art historian specializing in modern and contemporary art from North Africa, the Middle East and transnational. She holds a PhD from University College London and is a CAORC/Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Humanities Fellow at the Centre d’ Études Maghrébines à Tunis. She is curator of the exhibition Beyond Metaphor: Women and War at apexart, New York (27 May-31 July 2021) and author of scholarly articles, including in In Search of Archives, eds. Sarah Dornholf and Nadia Sabri (Berlin: Archive Books, 2021) and African Arts.

Illustrations: