meena Alexander (conversation)

Two Laments: Meena Alexander & Monika Weiss in Conversation

Moderated by Buzz Spector

in Monika Weiss-Nirbhaya, Centre of Polish Sculpture in Orońsko, pp. 79 - 89, 2021

The below are excerpts from an unpublished, transcribed conversation between artist Monika Weiss and late poet Meena Alexander that was moderated by Buzz Spector. The recorded conversations continued intermittently from 2015–2018, until Alexander’s untimely death in Fall 2018.

Introduction:

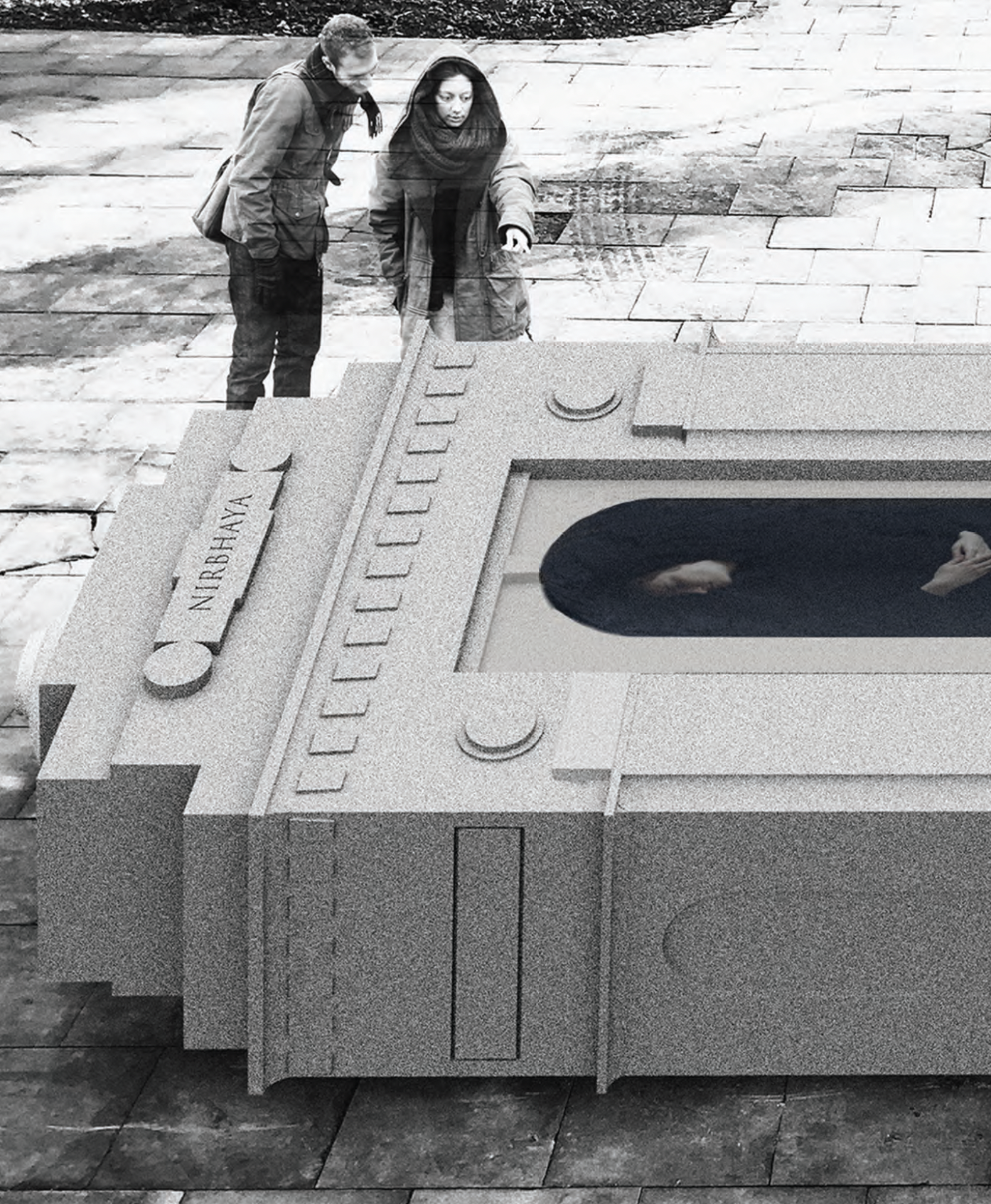

Canto 4 is part of Monika Weiss’ Two Laments (19 Cantos), a series of projected film and sound works shown in Orońsko in Spring 2021. Canto 4 includes the poem, Moksha, by the late Indian poet Meena Alexander, which she dedicated to Nirbhaya. The original aspiration for the transcribed dialogue between Weiss and Alexander was to publish a little book incorporating words and examples from their parallel arts. The subsequent realization of Nirbhaya monument, as well as this monograph, were not yet a factor in that 2015 conversation, but the ideas about trauma, healing, and wrath which were then spoken certainly foreshadow the monumental project that Weiss has since developed for Orońsko and for the world. Special thanks to historian David Lelyveld, Meena Alexander’s husband, for permission to publish these excerpts from the conversation.

Conversation:

BUZZ SPECTOR: I come to this conversation with the fresh experience of seeing four of Monika’s 19 Cantos from the ongoing series. The tone of the work I saw, its langua, is of a peculiar combination of sorrow, wrath, and desire. Perhaps some framing of its iconography is useful for us to begin.

MONIKA WEISS: In October 2014, I was invited by Amit Mukhopadhyay, a curator in the public sphere based in Kolkata, India, to create a new project in relation to the city of Delhi. I conducted intense and intuitive research into the history of the city while continuing my work on lament in relationship to postmemory. [1]

I focused on two sites of trauma: the recent brutal gang rape of Jyoti Singh[2] (posthumously named Nirbhaya[3]) which took place on a moving bus, on December 16, 2012, and the colonial residue of India Gate memorial [4], whose foundation was laid on February 10, 1921 by the Imperial War Graves Commission [5]. Two Laments (19 Cantos) [6] became a series of 19 short experimental film projections considering two kinds of trauma: personal and public, exploring how narratives of war and gender-based violence are selectively memorialized and actively erased within social and political consciousness. In court transcripts of the gang rape trial [7], I found a statement by one of the perpetrators who remembered seeing a red ribbon coming out from the woman’s body, which upon further investigation revealed itself to be her intestines. 19 Cantos begins with a prelude composed of silent text, which I wrote while in India, set in bold white font against a black background. Composed in stanzas of two lines each, the text evokes the voice of Nirbhaya, as if she was resurrected to appear as a witness. The text is repeated by different female voices speaking in various languages throughout the 19 Cantos. It begins with the statement, “This is my ribbon/ taken out of my body by you.”

The 2012 gang rape lasted almost two hours as the bus moved through the city of Delhi, and this, I felt, implicated the entire city and, by extension, any city around the world. Jyoti Singh’s body was taken inside out in a horrific and transgressive culmination of the act of the rape itself. This fact became a catalyst for the entire project of Two Laments (19 Cantos). My 19 film projections show slow, repetitive movements of silent lamentation performed by young women volunteers whom I choreographed and filmed in New Delhi and also in New York. In many of the short films, the red ribbon appears as a veil that my performers hold close to their abdomen. In Canto 3[8] the veil poetically enshrouds the aerial view of Old Delhi, which becomes a meta-city, standing for all cities bearing traces of historical trauma. I wanted for the memory of this horrific rape to have a kind of gravity corresponding with the grand architecture of India Gate, which is a triumphant arch. The work couldn’t be monolithic, it had to be fragmented, pulsating, and circular in the way it conceives time. To put this work in the context of desire is interesting and unexpected. Perhaps desire appears as a form of beauty — which I found within the land, within the body. The map of the old city of Delhi, as it is shown in Canto 3, evokes an impossible-to-conceive loss of old cultures and lives, which is difficult to describe in words.

BUZZ SPECTOR: You are recalling both the inception of your process and the trauma, which was catalytic for your work to occur. The trauma is vivid and, like all trauma, it disturbs language.

MEENA ALEXANDER: Having just seen the piece again, I was very struck by how the slowness of the body and the slowness of the movements in Monika’s Cantos is iconic in the way that, imaginatively, we have to embody something in order to make art. When I work on a poem, I feel like it is being immersed in an emotion and then it has to irradiate me. Living in that way, it can become difficult to cross the street or do ordinary things. You asked me earlier, Buzz, about time in Monika’s work. I was very struck by it. It felt just right to me. There is a meditative embodiment of what lines or images cannot spell out: the impalpable. This is what I try to approach in my poetry. I think poetry is really an art of silence because the most that the words can do is to pitch you towards what, in the end, cannot be spoken, and might only dimly be embodied. We face the horizon of what cannot be named. I think this is where the link to trauma is powerful because, like ecstatic knowledge, it pushes you to a break in the grammar of the everyday.

I used to live in Delhi when I was 23. It took me two years to compose Moksha [9], which I started when I was riding a train from Parma to Modena. I glanced out the window and saw somebody who looked exactly like my sister-in-law, who had died several years earlier of breast cancer. It was completely uncanny. I wrote a few lines and stopped. Then this awful rape in Delhi happened. It was so shocking, but in a strange way not completely surprising insofar as something can be unsurprising and, at the same time, utterly shocking. I know the Munirka bus stop because I used to go there when I was at Jawaharlal Nehru University [10]. It was dreadfully hard to board a bus in those days when I was young and constantly being pinched and prodded. Delhi is a city that was built layer upon layer. There are several ancient cities beneath contemporary Delhi. When I look at India Gate, which is where all of the protests happened, I also think of the destruction the city suffered. After the great uprisings of 1857, the British raised the old city of Delhi [11]. In my 2013 book Birthplace with Buried Stones [12] I have a cycle of poems inspired by Mirza Ghalib, who wrote an extraordinary memoir in Persian, Dastanbuy, composed in the aftermath of the destruction of the city in 1857. [13]

BUZZ SPECTOR: Therefore, does the map, which appears in Monika’s Canto 3, precede India Gate?

MONIKA WEISS: Yes. I found this map-like aerial representational drawing titled The City of Delhi Before the Siege published on page 52 of the January 16, 1858 edition of The Illustrated London News [14]. In Canto 3, a performer appears as if she was lying down on this map. We see the city right before the siege by the British in 1857. The performer moves very slowly, dressed in a long black robe, which gradually becomes soiled by the dirt of the ground, as if stained by the city itself. At some point, she becomes two women overlapping and merging with each other. Ultimately, by the end of the projection, she and her double disappear, leaving headscarves laid over the surface of the city. I created a kind of split into two at the heart of the map. Because the map is equal to the size of the projected image, the projection also seems to be split. Additionally, the scale of the women’s bodies is equal to the scale of the city. This is significant to me because the city, any city, is therefore doubly marked and implicated.

MEENA ALEXANDER: I think the rape of a woman and the rape of a city are important in your work. In Urdu, there is a form of lament for a city called marsiya [15]. What you are doing with the women in your Cantos is very beautiful because of the very slow movement. This approach feels right to me. Maybe this is the way we make sense of what, in the end, is so violent and so absurd. The work has to be very slow in movement and musical, since music exists in time and, unlike sculpture or a book, it does not occupy space. When your piece is over it vanishes, am I right?

MONIKA WEISS: Yes, it vanishes because it is like an act of mourning. But it also returns, like echo. The oldest known forms of archaic lament were conceived as an imaginary dialogue between a passerby and a tomb, which was ultimately an impossible communication with someone who is dead [16]. This archaic lament later developed into musical and poetic forms of refrain and incantation. The specific technique of montage with which I construct my projections and sonic compositions involves the reversal and layering of images and sounds to create a space of circular time akin to this method of incantation.

I liked when you said that poetry is about that which cannot be shown. I think art also deals with things that cannot be shown. At least in my work they cannot. Time and again, I am drawn toward working with the most difficult subjects and traumatic sites, fragments of memory, and historically forgotten or erased events. However, one cannot show or “speak” those sites or events. As a result, my work seems to reside in a liminal space between showing and not showing, speaking and not speaking.

MEENA ALEXANDER: I think the unspoken question is where you put your own body as you face something that is too terrible to be borne. How are you implicated in it and what is the right and delicate place for you? You can’t appropriate it; it is not yours. You are a witness, but what does this mean? I wrote a whole cycle of poems, Letters to Gandhi [17] set in Gujarat in 2002, after the violence perpetrated against Muslims [18]. I visited the relief camps with a friend who was collecting eyewitness testimony for the People’s Union for Democratic Rights [19]. I sent the poems to a friend in Delhi, who then forwarded them to his friend working for The Hindu. The newspaper carried the whole cycle, which was quite unusual for it.

I can’t forget how the editor wrote to me about the great beauty of the poems, and how it brought to mind what people who are suspicious of art think: how can you make a thing of beauty out of such terror? I wrote back to him that it seemed to me that the task of beauty was to return us, in some measure of tenderness, to the earth from which we were cut away, precisely by the extremity of violence. I then included this exchange in an essay entitled “Fragile Places,” which is a reflection on making art in a time of violence. This essay is included in my book of essays, Poetics of Dislocation [20]. Art does have a job to do: it involves working with beauty.

MONIKA WEISS: The city understood as a public space protects its public memory and, in a way, it doesn’t want to be “polluted” by traces of crimes against the bodies of women. A woman’s rape is often culturally associated with victimhood and actively erased from cultural memory. The body of a woman in the public sphere is the body of flâneuse. In Canto 3, Nirbhaya’s body becomes the size of an entire city. I am altering the scale of her body to make a point.

MEENA ALEXANDER: This is precisely on target. This is what you have to do in order to make sense of what is happening. The scales have to be altered. Working with the poem was an experience of temporality that I had to resolve. I began writing the poem in Parma and finished it two years later in Shimla because I felt it had to be finished in India. I also needed the distance in time and, in that sense, it was about musicality. The turning point in my poem is when I see the two women and when I hear them sing.

MONIKA WEISS: This is such an important moment in your poem, when you state that you see and hear two women. This stanza became the reason for me to include Moksha in Canto 4. This piece is silent. We see a close-up of a woman standing against a bare wall, facing us with her eyes closed. She slowly lifts her head to the point of the limits of the gesture, and then returns and bows all the way down until she almost disappears from the frame. This movement repeats several times throughout Canto 4.Twice during the 4 minutes of the video the protagonist opens her eyes and stares directly at us. I was interested in creating a specific counterpoint between each two lines of Meena’s poem — which appear at the bottom of the projected image as if they were a subtext in a film — and the gradual motion of the woman’s head.

At some point only one, partial sentence appears, taken out of the context of the rest of the poem, “before all our tongues began.” After that line appears in the video, there is a long pause. Yesterday, when you read Moksha as part of a public reading in The New York Public Library, it was beautiful, but it felt much faster than how I heard it in my imagination. “Before all our tongues began” could be the beginning of a sentence or an end. To me “before all our tongues began” means we are in a liminal place where this particular rape occurred. This is a particular city and a specific body, which stand for all rapes and all cities. In Two Laments the site of trauma, Nirbhaya’s body, is performed and inhabited by many women, symbolically reverting our gaze. In Canto 4, her body places us in the speechless, within the “before the tongues began” space. We are in the space of lament because we cannot utter the horrific.

MEENA ALEXANDER: Those two lines came on a separate page in my notebook, because they were so important. They took me back to emotions I’d had when I was in my twenties in Delhi, to a rose garden there. It is a city of amazing, gorgeous flowers. I think there is something in the way in which extreme violence, as well as the specificity of what occurred to Jyoti Singh, has to dissolve into something else that is more of a cypher. Perhaps this relates to what you are doing in your work. I think this is the task of the work of art, and it is a very delicate, intense sort of activity. You are negotiating between fierce injustice, the horror of violation, and the ethics of beauty. That is why I love what you did with the slowness of her gestures, and of composition. Toward the end of Canto 4, she is looking at us. There is another thing that she is seeing, which is perhaps desire.

It is believed that fifty years have to pass — a whole generation or perhaps more — before communities are able to face up to violence perpetrated on a large scale. It was the case in some ways with the bloodshed in the aftermath of the Partition of India [21]. Sometimes we feel called upon to make a certain work of art. I have not lived in Germany. I was only in Palestine for a little over a month. You have not lived in India before. That is not what our work is about.

I think each artist has a particular DNA and a particular palm print that structures the work of art. This makes the work unique. And this also allows you and I to respond to each other’s work in intimate ways. In 2005, I wrote a poem called Aletheia[22] inspired by your sculpture and performance piece, Lethe Room. What fascinates me about your work is the way you use the body, which I admire and find moving. How you employ the body allows you to touch the place that is behind what we are consciously aware of. Perhaps this is also what I try for in my poems.

BUZZ SPECTOR: This is what interests me. The pacing of your poem is apportioned by Monika into two-line bits. Each bit was on screen for a long while. I am focusing here on the difference between the speed of Monika’s movements as enacted on camera and the speed we assume such gestures occupy in real space, in real time. Meena, I assume you would read your poem with a crisp pronunciation? You wouldn’t linger over each word to the length of time that those stanzas appear now in Monika’s Canto 4.

MEENA ALEXANDER: Yes, it felt as if Monika returned it to a kind of music.

BUZZ SPECTOR: Nothing is being spoken. We are reading. The words do not become empty glyphs in a scene whose action is only that of the woman. We read again and again. We read each two lines against their attachment to that face. The astonishing renewal is that each stanza of your poem in turn allows the question, “is this that woman?” to be asked again. She shifts from being your sister-in-law to being Nirbhaya, then becomes both.

MEENA ALEXANDER: During our previous conversation at Maribelle, you asked me something, Monika. We both spoke about doubleness in our work. I think this is very important in your composition. Later, after our meeting, I thought about it on the subway. Two things came to me. The sage Valmiki, standing at the edge of a river watched two mating birds. The male was struck by an arrow and killed. The desolate bird who survived cried out so piteously that the poet’s soul filled with emotion, and he was moved to compose the epic Ramayana.[23] The other thought also involves two birds, and this also came to me in the speeding subway. It is the notion of sakshi,[24] that we find in the Upanishads.[25] Two birds are on a tree; one is enjoying the taste of the ripe fruit on the tree, the other watches silently. The second bird is the witnessing consciousness. We need both selves, both birds, in life and in art. Think of Valmiki, that is, the way the poet writes. There are two birds and one is shot, then out of the emotion of that grief comes the poem. There are always two, at least in certain strands of ancient classical Sanskrit aesthetics. Not one, but two.

BUZZ SPECTOR: It is very important that one becomes two, or that there is one woman seen twice. The one does not stay one. Two images of one person can’t be sustained imaginatively, even as one person seen twice, without some further act, some hallucination one conjures up as an implement to create an impossible separation. We are all more than one. The image becomes one and the other; the one with the other, the one as the other. The encouragement we get happens through your armature, which is itself double. In Canto 3 the page is double, so that the inscription repeats itself, impossibly, though the map itself is continuous. But the map has the fundamental property of the book — that gutter, that seam where two become one. Two become one in the book, one becomes two in the body, and then there is the speed of movement which corresponds to the turning of a page. You even provide us with the black scarf and the reds scarf, as pages.

MEENA ALEXANDER: And so that in Canto 4, each stanza becomes a page that turns. The entire space is given to the couplet. Both you and I have elegiac imaginations. “We have poetry so we do not die of history”, I wrote somewhere [26].

You and I face the muse of lamentation. There are artists and poets who are not like us, who have a very different way of inhabiting the present. Both you and I have memory taking the front space. Maybe this is why doubleness comes through as the mnemonic posture.

Notes:

[1] Marianne Hirsch’s notion of “postmemory” describes “the relationship of the second generation to powerful, often traumatic, experiences that preceded their births but that were nevertheless transmitted to them so deeply as to seem to constitute memories in their own right.” From “The Generation of Postmemory,” Poetics Today, 29:1 (2008), p. 103.

[2] 23-year-old Jyoti Singh and her friend Awindra Pratap Pandey were assaulted on a moving bus on the night of December 16, 2012 in Munirka, New Delhi. Jyoti Singh was brutally gang raped by six men after her friend was beaten unconscious, and she later died of her wounds. See “Delhi gang-rape victim dies in hospital in Singapore,” BBC News (December 29, 2012).

[3] Nirbhaya, meaning “Fearless” in Hindi.

[4] India Gate is a monument constructed to commemorate 70,000 Indian soldiers who were killed in the First World War. The foundation stone was laid in 1917 and the memorial was inaugurated in 1931.

[5] The Commonwealth War Graves Commission was established by a royal charter 1917 to “sustain the commemoration of the war dead, which after WWII numbered 1.7 million, in cemeteries and on memorials in some 150 countries.” The Commission operates upon the principle that “each of the dead should be commemorated individually by name either on the headstone on the grave or by an inscription on a memorial; that the headstones and memorials should be permanent; that the headstones should be uniform; that there should be no distinction made on account of military or civil rank, race or creed.” Peter J Francis, “Commonwealth War Graves Commission,” The Oxford Companion to Military History, edited by Richard Holmes, Charles Singleton and Spencer Jones, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

[6]Two Laments (19 Cantos) by Monika Weiss: Film, sound, drawing and text work developed during an artist residency at the Sanskriti Foundation in New Delhi, 2015. Two Laments were inspired by ‘Treny’ (19 lamentations) by the 16-century Polish poet Jan Kochanowski on his daughter’s death. This work is dedicated to Jyoti Singh.

[7] In court transcripts of the trial I found a statement by one of the perpetrators, who remembered seeing a red ribbon coming from her body.

[8] Canto 3 from Two Laments (19 Cantos) depicts the body of a woman performing lament superimposed upon the map of Old Delhi. A red ribbon is pulled from her body and poetically enshrouds Delhi, which becomes a meta-city, standing for all cities bearing traces of historical trauma.

[9] Meena Alexander, “Moksha,” The Hindu (December 7, 2014). For more information on The Hindu newspaper, visit http://www.thehindu.com/.

[10] Jawaharlal Nehru University (founded in 1969) is a public University in New Delhi. For more information regarding the foundation of the university and its vision, visit http://www.jnu.ac.in.

[11] On May 10, 1857, “three hundred mutinous sepoys [Indian infantry] and cavalrymen from Meerut rode into Delhi, massacred every Christian man, woman and child they could find in the city, and declared Zafar [the last Mughal emperor] to be their leader.” The British blockaded Delhi until it was on the brink of starvation and on September 14th, the British took the city, “sacking and looting the Mughal capital and massacring great swathes of the population. In one muhalla [neighborhood] alone, Kucha Chelan, some 1,400 citizens of Delhi were cut down. ‘The orders went out to shoot every soul,’ recorded Edward Vibart, a nineteen-year-old British officer.” Wiliam Darlymple, The Last Mughal: The Fall of a Dynasty, Delhi, 1857, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007, pp. 3–4.

[12] Meena Alexander, Birthplace with Buried Stones, Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2013.

[13] “The city of Delhi was emptied of its rulers and peopled instead with creatures of the Lord who acknowledged no lord — as if it were a garden without a gardener, and full of fruitless trees,” Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib, Dastanbuy: A Diary of the Indian Revolt of 1857, Translated by Khwaja Ahmad Faruqi, New York: Asia Publishing House, 1970, p. 33.

[14] “The City of Delhi Before the Siege,” The Illustrated London News, January 16, 1858, p. 52. The Illustrated London News was a weekly illustrated news magazine that reported on international events. Published only four months after the Siege of Delhi ended, the image shows a picturesque city that had been recently destroyed.

[15] “The term marsiya (elegy) derives from the Arabic risa, praising (the dead) in a funeral oration, weeping and wailing over the deceased. A marsiya is a poem about the good qualities of a deceased person, recited to express sorrow at his death; a poem to commemorate a pathetic event.” The marsiya developed in the Deccan states of India as a form of Persian/indigenous poetry and flourished throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The form spread to North India, where marsiyas were composed in Urdu, in addition to Persian. Marsiya is a ritual performance of mourning, an elegiac musical form as well as a literary genre. Madhu Trivedi, “Invoking Sorrow: Marsiya in North India,” Traditions in Motion: Religion and Society in History, edited by Satish Saberwal and Supriya Varma, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005, pp. 127–131.

[16] For further reading on Lament see Lament: Studies in the Ancient Mediterranean and Beyond, edited by Ann Suter, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008, and Margaret Alexiou, The Ritual Lament in Greek Tradition, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2002.

[17] Meena Alexander, “Letters to Gandhi,” The Hindu (July 6, 2003).

[18] On February 28, 2002 in Gujarat, India, an anti-Muslim pogrom began that lasted for three days. Muslim homes and religious structures were destroyed, Muslim businesses were boycotted and Muslims were murdered. After three days, 150,000 people had been forced out of their homes and more than 1,000 people lay dead, the majority of whom were Muslim. Several mass killings and other instances of violence occurred in the following months. The violence was enacted through a “script” of “Hindu awakening,” as purported in media sources. Anthropologist Ghassem-Fachandi argues: “the effervescent experience of ‘Hindu awakening’ is a veritable dissolution and rebirth into a social collective held together by negativity. It awakens destructive impulses, a nihilist guarantee of group cohesion, that enable an abreaction in an orchestrated environment, one often termed ‘riots,’ which, while carrying many incalculable risks, appears nonetheless micromanaged and controlled.” From Pogrom in Gujarat: Hindu Nationalism and Anti-Muslim Violence in India, Princeton/Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2012, pp. 259–260.

[19] The People’s Union for Democratic Rights is a “civil liberties and democratic rights organization based in Delhi, India.” For more information visit http://www.pudr.org.

[20] Meena Alexander, Poetics of Dislocation, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2009.

[21] “On ‘Direct Action Day,’ [the day the Muslim League backed out of negotiations with Congress] 16 August 1946, violence broke out between Hindus and Muslims in Kolkata. Several thousand people were killed in four days. From here, the violence spread, one way and then the other, to engulf many parts of northern India by March 1947 …A British general wrote of the fierceness of the attacks and the rapidity with which they spread from the cities to the countryside. In the cities of Rawalpindi and Multan, ‘attacks were fiercer, more sudden, and more savage than ever. In the rural areas attacks were launched by large mobs of Muslim peasants who banded together from several hamlets and villages to destroy and loot Sikh and Hindu shops and houses in their area. In some areas savagery was carried to an extreme degree and men, women and children were hacked or beaten to death, if not burned in their houses’…Many people took their own lives, or those of their family members, rather than surrendering to bondage and dishonor. The collective suicide of ninety or more women and children in the village of Thoa Khalsa is now the best known of these incidents.” Gyanendra Pandey, Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 23–24.

[22] Meena Alexander, “Aletheia,” Quickly Changing River: Poems, Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2008, p. 28.

[23] “The Vālmīki’s Rāmāyaṇa is an epic poem of some 50,000 lines retelling in Sanskrit verse the career of Rama, a legendary prince of the ancient kingdom of Kosala in the eastern portion of north central India.” There is much disagreement concerning the original date of the poem, from the fourth century A.D. to the sixth millennium B.C. See Robert P. Goldman’s Introduction to The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984, pp. 4–5, 14.

[24] Sakshi meaning “witness” in Hindi.

[25] The Upanishads “record the inspired teachings of men and women for whom the transcendent Reality called God was more real than the world reported to them by their senses. Their purpose is not so much instruction as inspiration: they are meant to be expounded by an illuminated teacher from the basis of personal experience.” The authorship and date of origin of these texts are unknown, but they are included in the Vedas, which can be traced back to ancient Sanskrit hymns, dating from perhaps 1500 B.C. See Easwaran Eknath and Michael N. Nagler, The Upanishads, Tomales: Nilgiri Press, 2007, pp. 17–20.

[26] Meena Alexander, “Question Time,” Birthplace with Buried Stones, Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2013.

Born in Allahabad, India, poet Meena Alexander was raised in Kerala and Sudan. Her numerous collections of poetry include Atmospheric Embroidery (2018), Birthplace with Buried Stones(2013), and PEN Open Book Award-winner Illiterate Heart (2002). In her poetry, which has been translated into several languages, she explores migration, trauma, and reconciliation. Alexander’s honors include fellowships such as the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, National Endowment for the Humanities, Fulbright Foundation, Rockefeller Foundation, New York Foundation for the Arts, and Arts Council of England, as well as the Imbongi Yesizwe International Poetry Award, and the South Asian Literary Association’s Distinguished Achievement Award in Literature. Alexander was a National Fellow at the Indian Institute for Advanced Study, Shimla. She lived in New York City for many years, where she was Distinguished Professor of English at the Graduate Center/Hunter College, CUNY. She died in late 2018.