weronika elertowska (conversation)

Conversation with Monika Weiss

by Weronika Elertowska

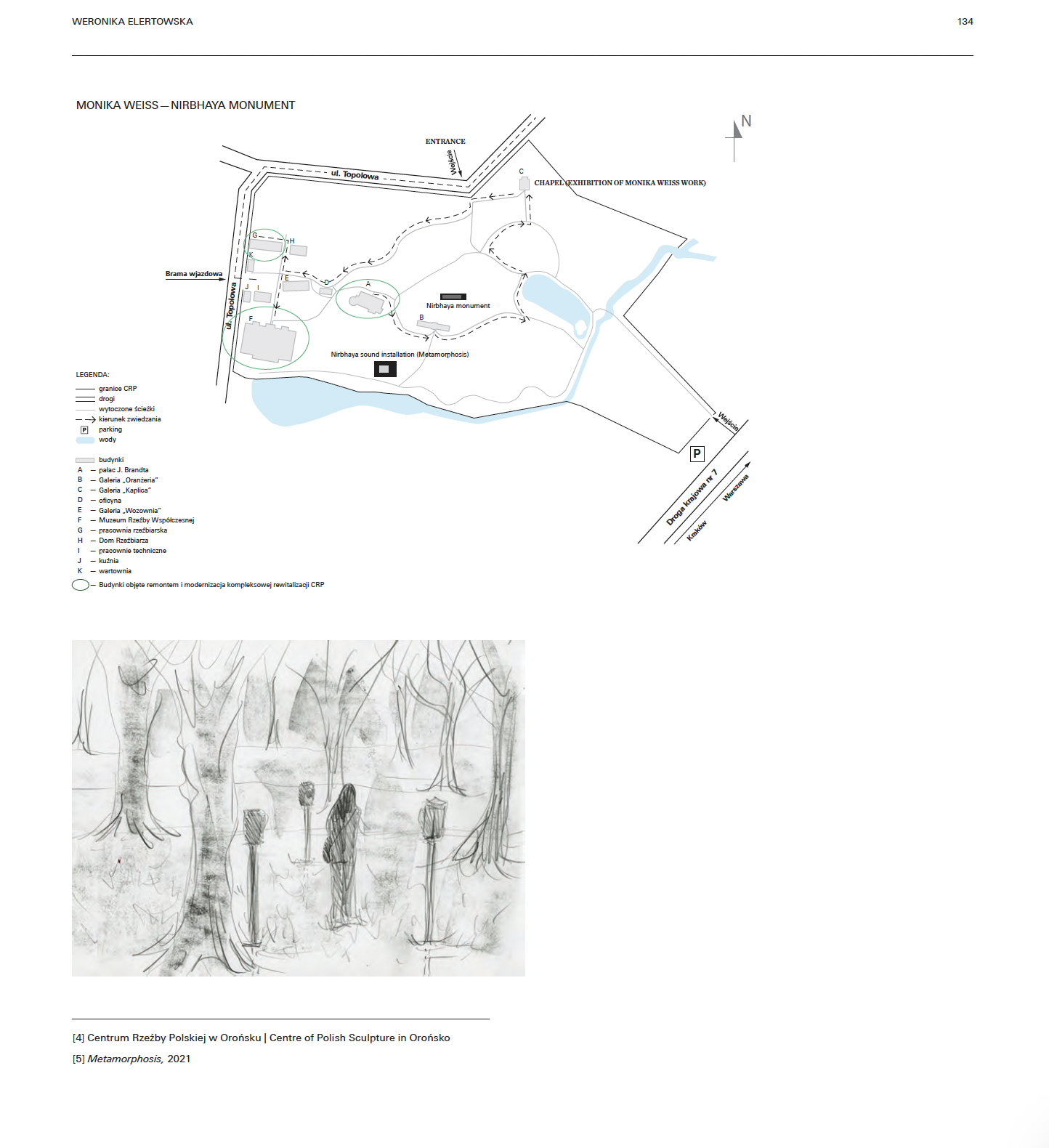

in Monika Weiss-Nirbhaya, Centre of Polish Sculpture in Orońsko, pp. 129 - 146

Introduction

Nirbhaya is a project for which perhaps the most obvious inspiration was the India Gate, designed by the British architect Edwin Lutyens with reference to the neoclassical architecture of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. Located in New Delhi’s most significant and representative site, the structure commemorates the 70,000 Indian soldiers who died serving in the British army the First World War and in the third Anglo-Afghan War.

Monika Weiss’ sculpture, which refers to these historical structures, reveals the artist’s firm feminist stance. The work’s origins can be traced back to the gruesome murder of Jyoti Singh, which took place in New Delhi in 2012. It is likely the first large-scale monument dedicated to the thousands of women who become victims of violence every day. The use of classicising aesthetics, frequently marshalled by colonial powers in the era of conquest, encourages us to broaden the scope of our reflection. The violent nature of the conquests of erstwhile conquerors remains a pressing issue and continues to shape our everyday. Monika Weiss presents us with questions about contemporary social roles and their resulting forms of oppression, as well as about the unnoticed suffering that falls outside of representation and commemoration.

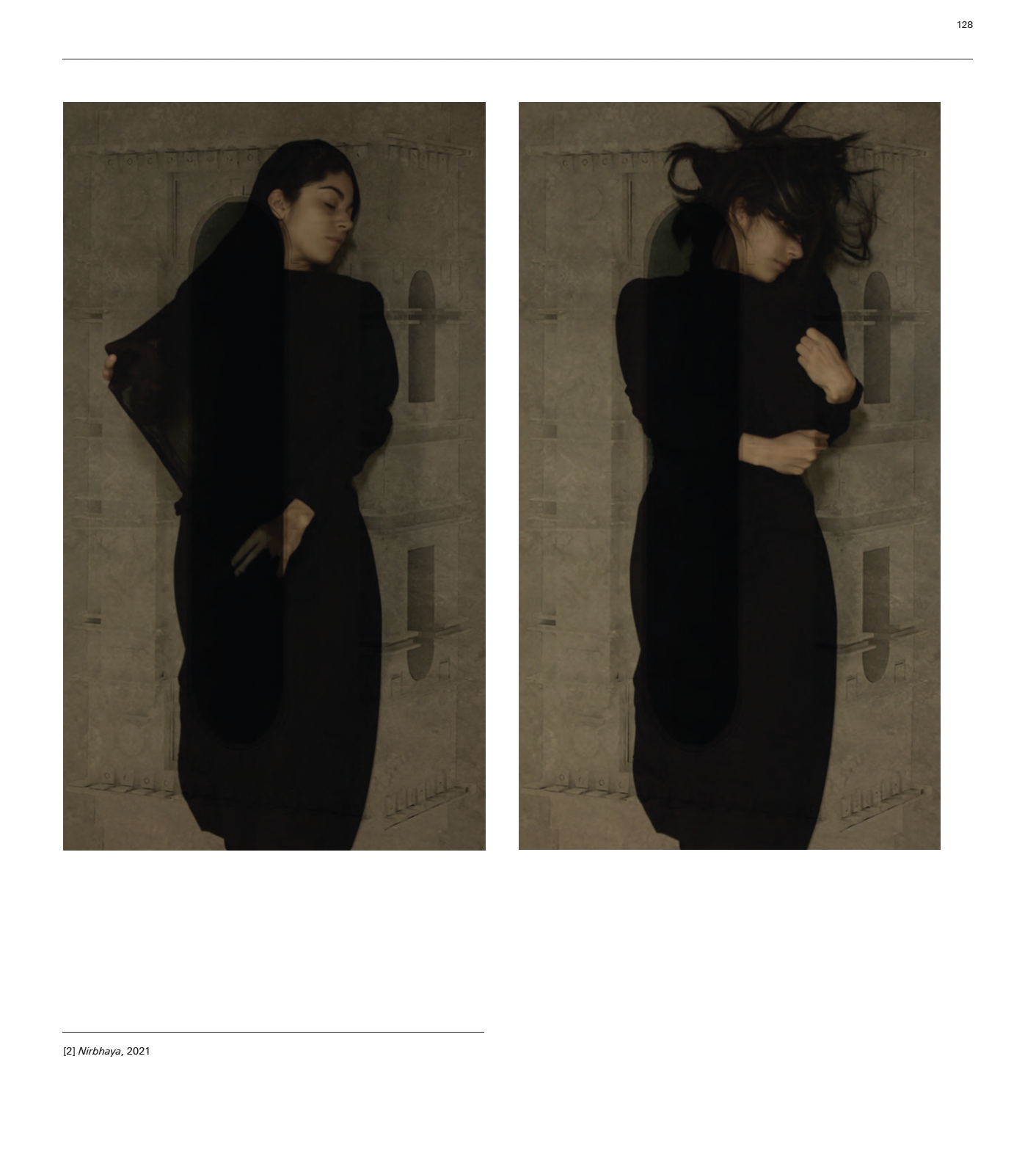

The artist’s project turns the triumphal arch into a water-filled, ancient sarcophagus. The India Gate, in turn, becomes a symbol of fluidity, losing its strength and heroism. Nirbhaya is also a project about leaning over a monumental form that no longer dominates us; about the possibilities of memory; about beauty becoming a response to history which viewers do not need to be familiar with as long as they can hear the murmur of water and the silence of the triumphal arch resting on the ground.

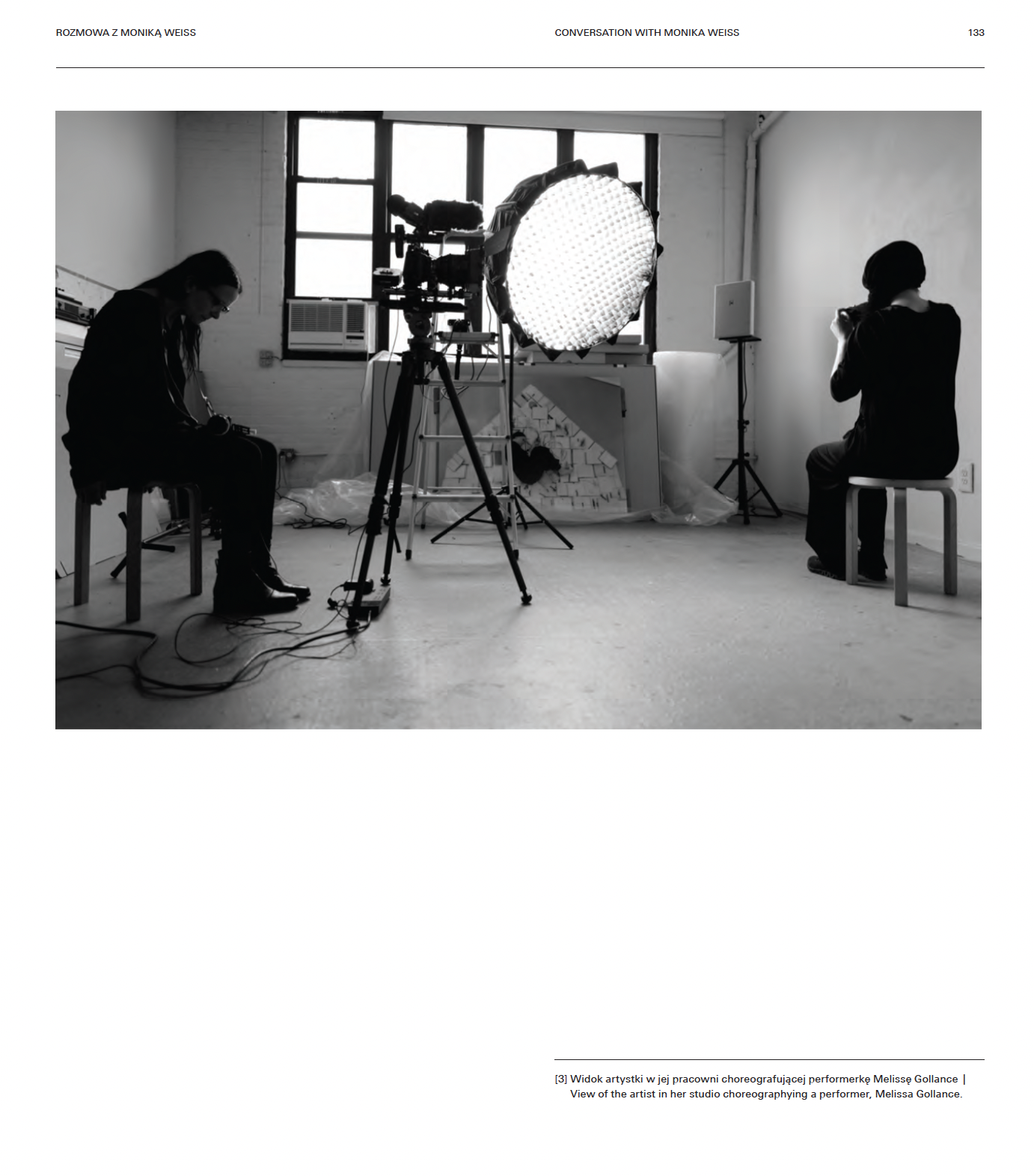

The following conversation is a transcript of several conversations with the artist recorded over the course of 2020.

Conversation:

Weronika Elertowska: I was struck by something you have frequently mentioned in our conversations regarding the presence of Jyoti Singh – Nirbhaya; it is a very interesting thread relating to commemoration. We spoke about the word ‘Nirbhaya’, meaning ‘Fearless’. Questions surrounding the permanence of commemoration immediately spring to mind. How do you relate to this? Or, in other words: how permanent are monuments, which can be destroyed or removed, when compared to the spoken word, which remains alive and present?

Monika Weiss: Time is the main material of my artistic practice. What happens in real time, at this very moment, now, but also at this other time, the time of collective memory. My monument offers an unforgetting of those who have been forgotten or erased from the collective memory. I propose a new model of remembrance by overturning the triumphal arch and transforming it into a horizontal sarcophagus, lying on the ground, the triumphal arch is doubled and filled with water. We can lean over this monument and see our own reflection in it. This form of commemoration remains close to the ground, horizontal, no longer victorious.

Weronika Elertowska: Is it not the case that we often sense that which is not physically present far more intensely than what we can tangibly experience? Especially nowadays, when we find ourselves in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and do not know what awaits us in a few months. Will we face an enormous economic crisis? How much longer will a globalised world feel sustainable? Might we reject this reality once the pandemic is over? Words are of great importance to you and you often integrate them in your work. It seems to me that there is an additional strengthening of the message relating to the problem of commemoration in Nirbhaya. A stone is usually associated with something durable, indestructible. However, if we recall what happened in Palmira in 2015, where ISIS terrorists blew up the cradle of civilisation, this form of commemoration seems far more fragile and ephemeral than oral history, speech, the memories that we carry within ourselves.

Monika Weiss: Palmira is a painful reminder of the fragility of culture, but not necessarily of its symbolic weakness.[1] Speaking about a monument is already a form of commemoration. My practice is concerned with the choices that are made to either remember certain figures, or to overlook and erase them from history; as is often the case with women. Monuments have gradually become unpopular or invisible, while anti-monuments have emerged as a way of addressing the workings of memory and the recovering of obfuscated memory. However, at this moment in history, citizens of the world are once again mobilised to remove ethically inadequate monuments and statues.

Weronika Elertowska: It seems to me that the use of stone in Nirbhaya – with all its symbolic and historical connotations – forms a meaningful manifesto on your part. Although you use such classical material in this project for the first time, there are other motifs woven through the work that appear in your earlier practice, such as water or sound…

Monika Weiss: Stone as a material refers to the earth, the ground; it suggests heaviness, lying, falling, corporeality. Equally, water exists as a physical material and as a symbol reminding us of ancient rituals of transformation, including baptism.[2] In some of my projects, including the Ennoia series,[3] I immerse myself for hours in a water-filled sculpture (which is created from fiberglass), inhabiting states of “syncope”[4] that lie outside of time and any specific place. I build water-filled sculptures and project a video onto their surface. In Nirbhaya, like in Ennoia, I suspend time and space by immersing a digital projection in water. I hope to create a site of a mythical and mythological experience, connoting rebirth and transformation. Both series of works are guided by repetition and incantation, inspired by the traditions of lament from which music was born.[5]

Weronika Elertowska: Let us return to Nirbhaya. It strikes me that the project is marked by defiance. Speaking about the different connotations of stone as a material, you refer to a form resembling a triumphal arch from New Delhi delicately placed on the ground. I deliberately describe it in this way as we usually associate lying monuments with a loud falling. Their toppling results from aggression or strong opposition, which we can assess in different ways – Palmira is a particularly grim example. At the same time, we witness the Black Lives Matter protests and the falling of monuments celebrating past heroes – racists, slave traders. In this context, the fall of Nirbhaya is radically different. Your attempt to overturn the old order associated with colonialism and chauvinistic attitudes resembles a quiet meditation. But it is also part of a new model of commemoration that seeks to restore the memory of previously overlooked attitudes, and critically re-evaluate past heroines and heroes. Black Lives Matter is an excellent example of this phenomenon – I am referring here to the recent actions around monuments which have taken place all over the world. The statue of the slave trader Edward Colston, destroyed by protestors, was temporarily replaced by Marc Quinn’s sculpture of a woman protesting against racism. Unsurprisingly, critics began to debate whether it would not have been more poignant to leave the monument empty or keep the fallen statue where it lay.

Monika Weiss: In Nirbhaya, we witness a “laying down”, which is an active process. I place the triumphal arch on the ground and transform it into a sarcophagus, into a khôra filled with water.[6] I am concerned with the moment of transforming one form of memory – victorious, vertical memory - into another, horizontal memory, existing in the sphere of lament. The Nirbhaya monument accuses the city – any city – of forgetting, condoning, raping and murdering its own daughters (‘daughter of India’).[7] Nirbhaya is what I call a place of unforgetting. I wish to ensure that women who are raped, tortured and killed are included in processes of commemoration and homage, in the same way as fallen soldiers are. Women are far too often erased from the collective memory, and placed beyond or outside of public sphere. As a poetic and symbolic project, Nirbhaya is also the tale of a horizontal ascent in our collective consciousness. Paradoxically, flight and lying down, and even falling, are visually linked. The sarcophagus is a place that is not only equal to heroism, but also situated above and beyond any state of heroism.

Weronika Elertowska: We often approach histories commemorated by monuments with great trust, if not entirely uncritically. If an event or figure were deemed worthy of commemoration on a monumental scale, we assume that they must be of great significance and therefore deserving of being remembered. A monument conveys a collective memory since witnesses to history will eventually pass away, not always being able to share their recollections.

Monika Weiss: A monument is an active site, always undergoing transformations. It is a conversation that exceeds the length of an individual life. A monument exists on its own as a fact. I wish for Nirbhaya to become an indisputable fact. Giorgio Agamben writes how culture, especially in so-called “developed” countries, conceals its own violence while, at the same time, creating homo sacer – victims of its own violence. Seeing the India Gate affected me deeply as it forms a marker of a colonial power that appropriated a city’s symbolic space. For me, this enormous structure not only commemorate Indian soldiers; but, having been erected by the British Empire in the centre of New Delhi, modelled after Paris and built in response to the destruction of Old Delhi by the British in 1858, it forms a rape of “low” culture by “high” culture, fixed in stone.

Weronika Elertowska: You speak of the cultures of “developed” countries, but these cultural differences between East and West, woman and man, are often nothing more than a myth and seem of little relevance here. People enjoy feeling superior to others and it does not matter if they justify this sentiment through gender, social status or geographical location. It is always based on one binary opposition: we – the superior ones, them – the inferior ones; the subjects versus the conquerors. This provokes aggression and a distinct view of the “other”, who becomes dehumanised. The colonisation of India, as well as of the many other places conquered by empires unfolded according to a similar logic. Violence is always closely linked to a feeling of superiority. These two problems appear as complementary in Nirbhaya.

Monika Weiss: The monument was inspired by two events and two sites of trauma: the body of the raped, tortured and eventually murdered woman, and the body of the colonised, destroyed and culturally raped city. This duality resonates with other places in the world. Much like my other public projects, Nirbhaya too does not merely speak of one triumphal arch, one woman or one city. Rather, it offers a space where one can feel and envision the possibility of another world, a world without violence, rape and the colonial conquest of cities. Are we capable of imagining such a world?

Weronika Elertowska: Your works seem to question contemporary value systems, as well as identity formation, which sometimes can be based on exclusion or oppression. A recurring theme in your practice is the trauma of the Holocaust and the Nazi plot.

Monika Weiss: Yes, my art often emerges as a form of questioning as to how we construct systems of meaning in our collective memory. I oppose truisms such as “human nature” or any form of biological determinism. I am interested in the utopian thinking that defined the Enlightenment, which remains an unfinished project of an entire civilisation, akin to the incomplete project of modernity. Zygmunt Bauman likens modernity to a garden,[8] where one is tempted to remove all weeds. In this vision, the garden evokes genocide and the Holocaust, while the gardener is a fascist, a dictator. Hence, modernity has failed us. Still, a monument remains an opportunity for transformation, which is based on unforgetting and poetry.

Weronika Elertowska: Nature is often used as a justification for negative behaviours. It is interesting that we explain certain things through its prism, such as the entirely artificial division based on the assignation of “male” and “female” roles. As if we could not simply acknowledge that we are all humans and that this universal quality does not need to be followed by forms of classification. It is difficult for us to move beyond this imposed framework, although modernity is lending a helpful hand. You once mentioned your interest in the figure of the flâneur. How do you think of it in relation to Nirbhaya? It seems difficult to identify with such a figure; at the same time, Jyoti Singh’s longing for independence and her tragic death broke through established schemes. She embodies everything that remains forbidden to women of different cultural backgrounds.

Monika Weiss: I am interested in the meanings of the flâneuse, which is a figure contested a priori in almost every culture, precisely because of its gendered aspect. Ever since Charles Baudelaire wrote about the flâneur, followed by Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project, we think of a figure from a century ago, standing on the threshold of modernity. But this figure, this free person, is always a man, always white, most likely wealthy, strolling aimlessly, a voyeur of the city and the world, a bit of an artist-creator. Women, in turn, only gain the cultural consent to be flâneuses when they are streetwalkers,[9] as in the nineteenth-century Paris described by Walter Benjamin.

Weronika Elertowska: This has of course a radically different meaning.

Monika Weiss: In every culture, whether ancient or modern, women are a target, an object. In Western cities, this is predominantly manifested through invasive looking, scopophilia. The actions of the #MeToo movement have led to a more rigorous punishment of real harassment. Still, in many and all cultures, the gaze can turn into a physical act of aggression, attack and murder, as in the case of Nirbhaya, precisely because there is a cultural consent for the male gaze.[10]

Weronika Elertowska: Two problems emerge in Nirbhaya. On the one hand, you speak of violence against women, for which there is still consent. On the other hand, you mention colonialism, violence against a city, its inhabitants, their culture, which you compare to the rape of a woman. Your project grows out of a specific tragedy, the brutal rape and murder of the young Indian woman Jyoti Singh who was returning home by bus. It is a very brave appropriation, especially that, at first glance, it seems difficult to equate the suffering experienced by a person with an attack on culture. You draw on New Delhi’s famous India Gate – a 42-metre-high monument inspired by the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, built by Edward Luytens as an example of ‘civilised’ architecture in the Far East. Though one has to emphasise that the very categories of the “Far East”, “Near East” or “the West” reflect a Eurocentric perspective.

Monika Weiss: During the trial, the perpetrators of the gang rape spoke of teaching a lesson to women all over the world.[11] They were agitated by the fact that a young, unmarried woman rides the bus at 9 o’clock in the evening, returns from the cinema with her boyfriend and acts as if this was her right. How dare she? Their mothers, wives and daughters should not behave this way; they should not be free. Nirbhaya is also their daughter, wife and mother. The Triumphal Arch in the heart of Delhi is thus a lesson, a symbolic act, at the level of commemoration.

In the video projection Nirbhaya, images of young women appear as a tribute in the form of lament, a threnody. Soldiers who die are usually also around 20 years old. The India Gate is covered with the names of young men, yet there are no monuments commemorating fallen women. It is us who decide who should be included in history books, whose lives our children should study, who can live on in sites of public memory, what kind of death deserves attention and whose lives are important.[12] In ancient Greece, mothers of the victors lamented alongside the mothers of the vanquished. Why then should we not be able to identify with another culture when it comes to rape and torture?

Weronika Elertowska: I wonder about your references – including aesthetic ones – to colonialism. We might say, from a Eurocentric perspective, that an educated woman from the West suggests how one should react to and emphasise the problem of rape in the (broadly defined) East. This may create new controversies and be interpreted as yet another act of colonialism, which it is not. The problem of rape requires total solidarity since women continue to face daily acts of aggression, harassment and rape in every corner of the world, including the US and Poland. A report published by the “Ster” Foundation in 2016 was alarming in this regard. It showed that nine out of ten Polish women had experienced some form of sexual violence, while 22% of those surveyed had experienced rape. This is shocking and frightening data. We like to think of a highly developed Western culture, yet chauvinistic attitudes are deeply rooted everywhere. Worst of all, the status quo is not maintained by men alone.

Monika Weiss: I do not identify with the West. I do not believe in such categorisations. As an artist I create poetic works that function as an act of solidarity with all women around the world. To oppose violence is not an act of colonisation, rather, a gesture against it. Speaking of humanity, we have succeeded in coining the term “human rights” - more or less globally - and introducing it into popular, cultural use, which is an important achievement of our recent past. For many centuries, there was a developed culture, but no human rights; the majority were enslaved people. I am interested in the sphere of invisibility and visibility (in Hannah Arendt’s understanding of these terms) in the public space, that is, the space of memory.

Weronika Elertowska: Coming back to the figure of the flâneuse, I think it is extremely interesting in the context of Nirbhaya and her life, which can be read as an attempt to defy the culture she grew up in. Jyoti Singh was educated, she studied medicine. Her life was also an expression of nurturing her strength and independence, which was drastically ended…

Monika Weiss: The bus in which the massacre took place drove through the city – symbolically and literally cutting through it – with all its doors and windows closed. The wound was not only inflicted on the body of Nirbhaya, but also on the body of New Delhi; and the bodies of all cities in the world. I am reminded of the trains to Buchenwald[13] that travelled through the beautiful areas of Weimar; hearing cries for help, no one responded. In a sense, my project for the monument and the earlier series of 19 threnody-films represent an indictment of the city’s indifference, that is, of ourselves, of our own ethical dormancy. I wish for this monument to be an active place, physically beautiful and alive. In the projection, Nirbhaya is immersed in the water of life, free, sensual. She is every woman, she is me, she is you. She is commemorated as a heroine. Suspended in a pose of lament, that is, within memory, but also in the pose of a dream, perhaps a dream of a better world. Immersed in a sarcophagus, washed by water, she is protected by having been transformed into a tree, inside a khôra.

Weronika Elertowska: You mentioned her sensuality when speaking about the video projection. To me, it seems more like a sacral ecstasy. The female figure appearing in the projection can be situated within a longer, baroque tradition of ecstatic representations of saints, for example of St. Theresa. This reference and the context of the chapel in the sculpture park in Orońsko secure Nirbhaya’s place in a catalogue of contemporary saints, martyrs, as if you wished to build a new religious canon.

Monika Weiss: Nirbhaya’s torture and death will forever remain a horrific crime. But I would like to offer her beauty and remembrance, like the soft touch of a shroud, a kiss (in Polish “całun” [shroud] and “pocałunek” [kiss] are etymologically related), holding her existence that we can no longer restore. So it is a lament; but it is also a form of remembrance and an act of honouring.

Weronika Elertowska: I would like to return to the topic of preserving the memory of Nirbhaya. Your works are clearly concerned with commemoration, but they also oscillate around what we know from religious representations – you spoke of ecstasy earlier.

Monika Weiss: I am interested in Sufism, alongside traditions of meditation and ecstasy in general. In my earlier projects, I performed multi-hour-long immersions in cold water, which were a form of endurance for my body, as well as a place of transgression, a move towards an unattainable form of patience, towards a deeper hearing of the world. I have now worked with the challenges of silence for many years. People who come to my performances often have to endure silence for a long time. Sound appears in my work as the inverse of speech, collapsing words and language into space.

Weronika Elertowska: An aesthetics that refers, whether directly or indirectly, to religious representation often causes very strong reactions, particularly as we live in countries dominated by Christianity. At times, such projects are interpreted in a rather one-sided and simplistic way, leading to multiple, unnecessary controversies and misunderstandings. The public education in the field of art (to which unfortunately we attach less and less importance) and political factors, which fuel a simplistic reception of art and shallow controversy, are not without consequence here. We are well aware of the outcry and controversy – which essentially grew out of ignorance – surrounding the works of Daniel Rycharski, such as Strachy or Maurizio Cattelan’s famous La Nona Ora.

Monika Weiss: I do not use religious aesthetics. The veil or shawl that appear in the projection could be interpreted as a weeping woman’s quiff or shawl. It is a shroud. I am interested in the tradition of lament as a mystical moment, as a moment in which normativity breaks down. It also is the beauty contained in an emotional response.

Weronika Elertowska: What particularly strikes me in your project is the way you look at the idea of commemoration. The society and the culture in which we are brought up constantly remind us that the experience of being raped is something shameful, something we should hide. We do not usually see victims of sexual violence, people experiencing any kind of violence, as heroines, as those who resist. And yet theirs is undoubtedly a heroic attitude.

Monika Weiss: Presenting the victim as a heroic figure is my primary concern in this project. How can we properly honour someone without repeating the violence? How can we offer beauty and heroism to an individual life, as well as to all women experiencing violence? Jyoti Singh was raped in an extremely brutal way, her internal organs pulled outwards like a red ribbon that one of the criminals spoke of. After a few hours, her body was thrown out of the bus in a terrible state. This is not a question of one country but of the whole world and, by extension, of a global cultural tolerance of violence and the objectification of women.

Weronika Elertowska: It would seem that Nirbhaya is not only a monument for women experiencing violence. Marshalling lament, you create a monument to the very right of mourning loss and to everyone fighting against violence. If, as you say, lament is a revolution, Nirbhaya becomes a monument to all revolutionaries fighting for a just future, not only women. The fight for equal rights has resulted in a widespread use of feminised linguistic forms. It becomes particularly evident in activists’ actions and in initiatives including the Anti-Fascist Year. Women and men who use feminine endings when referring to themselves identify with problems that predominantly concern women. This often arouses consternation and is treated as a type of game by right-wing and more conservative circles. It reveals a paradox. If using masculine forms to address an all-gender group does not provoke laughter, why then are we outraged at the feminine form of words such as manager, doctor, minister? Or when men and women use the feminine form to describe themselves as the participants of a conference. History of art imposes certain meanings pertaining to male and female bodies on us. Why should a woman symbolise lust and emotions, while the man stands for reason and intellect? The question is whether we still want to identify and agree with these symbols and stereotypes. Of course, we need to consider the historical context. From a contemporary perspective, interpreting women’s representations literally would result in many simplifications. Even in conservative circles, there is little discussion or resistance to rereading the Old Testament and treating it as a metaphor since the text is rich in violence. We should approach these symbols and social roles, which were developed hundreds of years ago, with great caution. By talking about the injustice caused by these divisions and about what happened to Jyoti Singh, and others, we are speaking out on an issue that affects us all. It is impossible to distinguish between rape culture in the USA, Poland or South America, because the roots of this discrimination are the same. As you mentioned earlier, the project is meant to return the right to sensuality to Nirbhaya. I also read it as a tribute to feminine power, which can manifest itself in different ways. In the context of Nirbhaya, the silence is even more pronounced and acts far more powerfully than any other sound. It carries more meaning, forming an emptiness after something had been lost – in this case, a senseless death.

Monika Weiss: As an artist I feel a certain necessity to respond to the trauma that I encounter - wherever it may be in the world - through poetic activity. Silence around Nirbhaya will be essential so as to create a moment of experiencing and hearing. But I do want some sound, situated in another part of the park, in a place where Nirbhaya has already morphed into a tree. Her skin has become bark; her words have turned into the sound of the wind. This metamorphosis, whose pain and beauty is reflected in the sound, remains in constant dialogue with the silent monument to Nirbhaya that represents a heroic history, and with the vibrating echo of the forest, where the Fearless whisper and sing for another world.

Weronika Elertowska: Sound has come up already earlier in our conversation. I know it forms an integral part of your work and is of great significance to you. I wonder why is there so much emphasis on music in your work? You have a background in classical music, but you could have as well negated and rejected it. This seems to be often the case, perhaps due to the restrictive nature of music education. It requires a great deal of effort and commitment and, above all, strenuous, routine practice and rehearsals, which may yield positive results only after years of perseverance. In your case, however, it is different – you have never rejected music and you still “use” it in its classical form. Why is this important to you?

Monika Weiss: My first intense experience with European music, so-called classical music, was the result of growing up in a home where my mother Gabriela Weiss, a pianist and piano professor, played the piano in our tiny flat. I do not consider sound as something to be used or exploited, rather as something that I create as a composer, sometimes in a very classical way, on score paper, with a pencil in hand.

Weronika Elertowska: Indeed, music has great potential to affect people, possibly because it stems from our primal desires, from lament as you often mention, affecting us intensely. I continue to wonder about sound and silence in your works, including in your public projects at the World Financial Center Winter Garden near Ground Zero (Drawing Lethe) or at the Whitney Harris Institute of International Law (Sustenazo VIII). It seems to me that you combine these two spheres in Nirbhaya. Sound and silence both mark this work, though you separate them. On the one hand, we have the triumphal arch, while, on the other, a sound station that is placed elsewhere. I myself wondered what would be more poignant in this work and whether sound in the monument was even necessary. But this remoteness and separation are very interesting, because we have the silence of the triumphal arch laid on the ground and the musical lament that is so central to your practice.

Monika Weiss: Visitors will be invited to wander, to make a short pilgrimage from a silent monument towards sound, strolling through the park like a flâneuse. Walking from the monument to the sound station, visitors will hear the sound that I composed as a form of post-traumatic space in which Nirbhaya becomes Daphne. Daphne dies as a woman, but at the same time becomes a living tree.

Weronika Elertowska: I am reminded of the beginning of our conversation when I wondered if words were not more durable than memorials. Oral memory transmission has for millennia been a form of commemoration. Music and sound emerge as forms of memory transmission, including collective memory. In folk traditions, memory was passed on through music and songs at a time when other forms of commemoration were not possible. The sound in Nirbhaya seems to emphasise even more what the stone is not able to convey.

Monika Weiss: The Nirbhaya project grows out of my long-standing interest in the history of lament as a form of protest, as an expression of women’s rage towards the world, towards violence, and war. The reason why women’s collective, organised lament was forbidden in ancient Athens was because it contradicted male behaviour – that is, rationality and strength.[14] In Nirbhaya, I propose a horizontal form of monumentality that no longer hides or erases the truth of violence.

Weronika Elertowska: Silence is of course also a form of sound. Marshalled in your practice, it encourages us to stop and think about the world that surrounds us.

Monika Weiss: Yes, I am delighted that there will be a sound station titled Metamorphosis in the park in Orońsko, which will form a part of Nirbhaya. I have been working with sound for many years now, as well as with silence, which is also sound, being its absence. There is also another silence, beautiful and painful. The silence of enduring. In many of my early performative and durational works, audiences witnessed this silence of enduring for many hours; but the same silence was expected from them. At stake was not only the perseverance of my body as a tool in my practice, but also of viewers’ bodies or, as I say, of those co-experiencers, who had to “endure” time and listen to its passing.

Weronika Elertowska: I wonder what role sound plays for you? I get the impression that in many of your works (Sustenazo, Nirbhaya) it offers ways of dealing with trauma. You received, as I mentioned earlier, a very classical musical education - you are a pianist and a composer. The frequent multi-hour-long practice and routine music rehearsals resemble, to some extent, a mantra, a meditation, the multiple repetitions have a cathartic power. After all, music is closely related to lament, forming one whole, as in the sung laments of weepers.

Monika Weiss: Yes, music and sound permeate and wash, sounds enshroud and at the same time resist classification. When the curator Erik Bruinenberg invited me to create a project in Potsdam in 2005, I had a dream about books burning. This was my first project in Germany (at Inter-Galerie, Nikolaisaal). My dream of books turning to ashes inspired the Phlegeton-Milczenie series of works.[15] This was the first time that I consciously referred to the tradition of lament and music in my art.[16]

Weronika Elertowska: In the context of Nirbhaya, it seems to me that the silence is very poignant and meaningful, an almost unbearable emptiness after something was lost – in this case, a meaningless death.

Monika Weiss: Yes, this metamorphosis, whose pain and beauty is reflected in the sound, remains in constant dialogue with the silent monument that represents a heroic history.

Weronika Elertowska: Thank you for this conversation.

Notes:

[1] Another form of destruction was enacted by the troops of the US-led forces in Iraq, which caused extensive damage and serious contamination of the remains of the ancient city of Babylon. Despite objections from archaeologists, the site was used by US and Polish troops as a military warehouse.

[2] Ritual cleansing was already known in antiquity. A belief in the purifying power of water was present in most ethnic primal cultures. The ritual of purification is still widely preserved in contemporary India, where millions of Brahmin devotees travel to the holy city of Varanasi for ritual bathing in the Ganges. Baptism is reminiscent of Tvilah, the Jewish purification ritual involving immersions in water, which is required for conversion to Judaism, among other things.[3] Ennoia is a series of baptismal font-like sculptures that I began creating in 2001.

[4] Syncope is a type of metrorhythmic disturbance in the flow of a classical music piece, used as a stylistic device. It is a rhythmic phenomenon that relies on the extension of a rhythmic value located on a weak part of a beat through the next one or through a beat group. Syncopation is accompanied by the creation of an additional accent, the so-called rhythmic accent, on the extended (weak) part of the beat. In medicine, “syncope” means fainting – a brief loss of consciousness.

[5] For further discussion on the connections between mourning traditions, and the history of music and poetry, see Margaret Alexiou, The Ritual Lament in Greek Tradition, Cambridge: University Press, 1974, and Dangerous Voices: Women's Laments and Greek Literature, Routledge, 1992.

[6] Khôra (also chora; Old Greek: χώρα) was the territory of the ancient Greek polis outside the city proper. The term was used by Plato in his Timaeus to denote a container (as a ‘third kind’ [triton genos]) which he understood as a space, a material foundation or an interval.[7] My earlier project Two Laments / 19 Cantos (Two Lamentations / 19 Cantos), dedicated to Nirbhaya, consists of 19 short film projections with sound. 19 Cantos was inspired by Jan Kochanowski’s Treny, 19 threnodies dedicated to his late daughter.

[8] In his work Modernity and the Holocaust (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989), Zygmunt Bauman attempts to understand why these terrible crimes took place in a modern society, at an advanced stage of its civilisational development and at the peak of its cultural flowering.

[9] To learn more about the concept of “flâneuse” see: The Invisible Flâneuse?: Gender, Public Space and Visual Culture in Nineteenth-Century Paris, eds. Aruna D’Souza and Tom McDonough, Manchester University Press, 2010. This collection of essays revisits gender and urban modernity in nineteenth-century Paris in the face of changes in the fabric of the city and social life. Using the figure of the flâneur, the authors analyse the public space of the city, taking Paris as an example, where men were allowed to roam freely while women were restricted to the privacy of the domestic sphere. [10] In feminist theory, the male gaze is the act of representing women and the world in the visual arts and literature from a male, heterosexual perspective that presents women as sexual objects, for the pleasure of the heterosexual male viewer. British film critic Laura Mulvey has used this concept to critique traditional media representations of the female figure in cinema history, see her ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, Screen, 16:3 (1975), pp. 6–18.

[11] We are not allowed to go out, or enter the public sphere, precisely because it is a sphere of meaning. Hence the ban directed at women - at the level of the law - in the cities of ancient Greece, and still in some cities today.

[12] The contemporary American philosopher Judith Butler asks whose life is worthy of remembrance and mourning and whose existence we deem unimportant in her book Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence, London: Verso, 2006. In doing so, she points to the possibility of radical social change.

[13] I also mentioned this in my article in the post-conference publication Sculpture today. ANTI-monument: non-traditional forms of commemoration, eds. Marta Smolińska, Eulalia Domanowska, Orońsko: Centre of Polish Sculpture, 2020.

[14] Women performed lament as actresses, and even today in Italy, it is possible to hire weepers who are not related to the deceased. They are hired individuals who continue this ancient tradition, because families often do not have the strength or capacity to show such public grief.

[15] Phlegethon is an ancient Greek mythological river of fire. Phlegethon-Silence was shown as a public project in Dresden in 2018 to commemorate the city’s destruction and liberation in 1945.

[16] That same year I created the installation Rivers of Lamentation as part of my retrospective at Lehman College Art Gallery. The installation of a huge canvas drawing on the ground - with a video projection on the nearby wall showing this scene from a bird’s eye view - began as a performance with Anthony Roth Costanzo. We lay on the ground, me drawing around my body and him singing fragments of laments from classical music, his voice refracted in this position, similar to the ‘refracting’ marks and lines I drew on pages torn from sheet music. We both had our eyes closed.

Curator, author of texts, and photographer, Weronika Elertowska is a graduate of photography at the Faculty of Multimedia Communication at the University of Arts in Poznań and Culture Marketing at the Faculty of Journalism and Political Science at the University of Warsaw. Scholarship holder of the Faculty of Photography and Media of the Academy of Fine Arts in Vilnius (2009) and the University of Arts in Cluj Napoca, Romania (2010), in her artistic practice, she works through the use of interdisciplinary methods, combining digital image recording with classical photographic processes and film. In cooperation with the Institute of Physical Chemistry of the Polish Academy of Sciences, she has been conducting research investigating the biological and chemical approach to memory in the context of photographic record, as part of the research program conducted by Dr. Emilia Witkowska Nera. Between 2016-2021, she was curator at the Center of Polish Sculpture in Orońsko and is currently project manager of Polish Romanticism at Adam Mickiewicz Institute in Warsaw.