buzz spector

Monika Weiss: Body of Drawing

by Buzz Spector

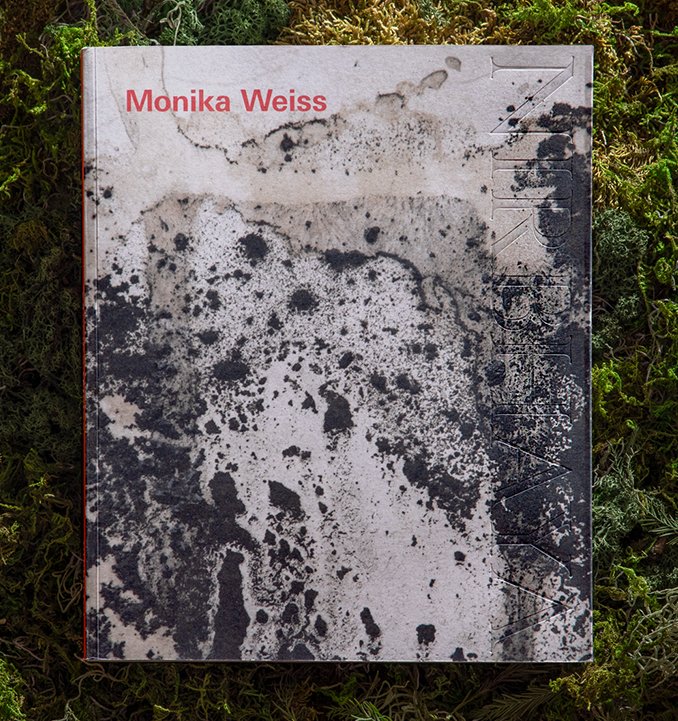

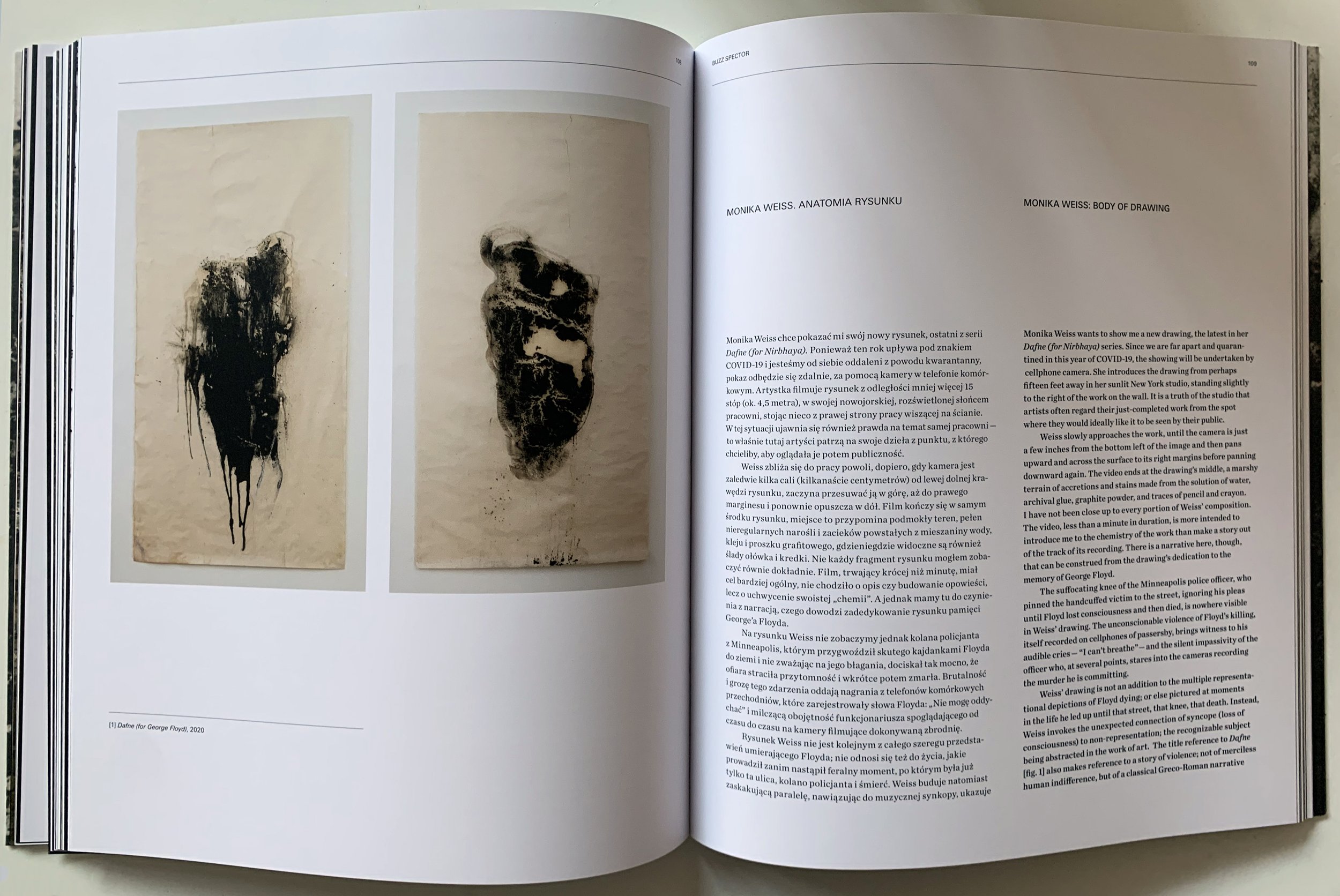

in Monika Weiss-Nirbhaya, Centre of Polish Sculpture in Orońsko, 2021, pp. 108 - 113

Monika Weiss wants to show me a new drawing, the latest in her Dafne (for Nirbhaya) series. Since we are far apart and quarantined in this year of COVID-19, the showing will be undertaken by cellphone camera. She introduces the drawing from perhaps fifteen feet away in her sunlit New York studio, standing slightly to the right of the work on the wall. It is a truth of the studio that artists often regard their just-completed work from the spot where they would ideally like it to be seen by their public.

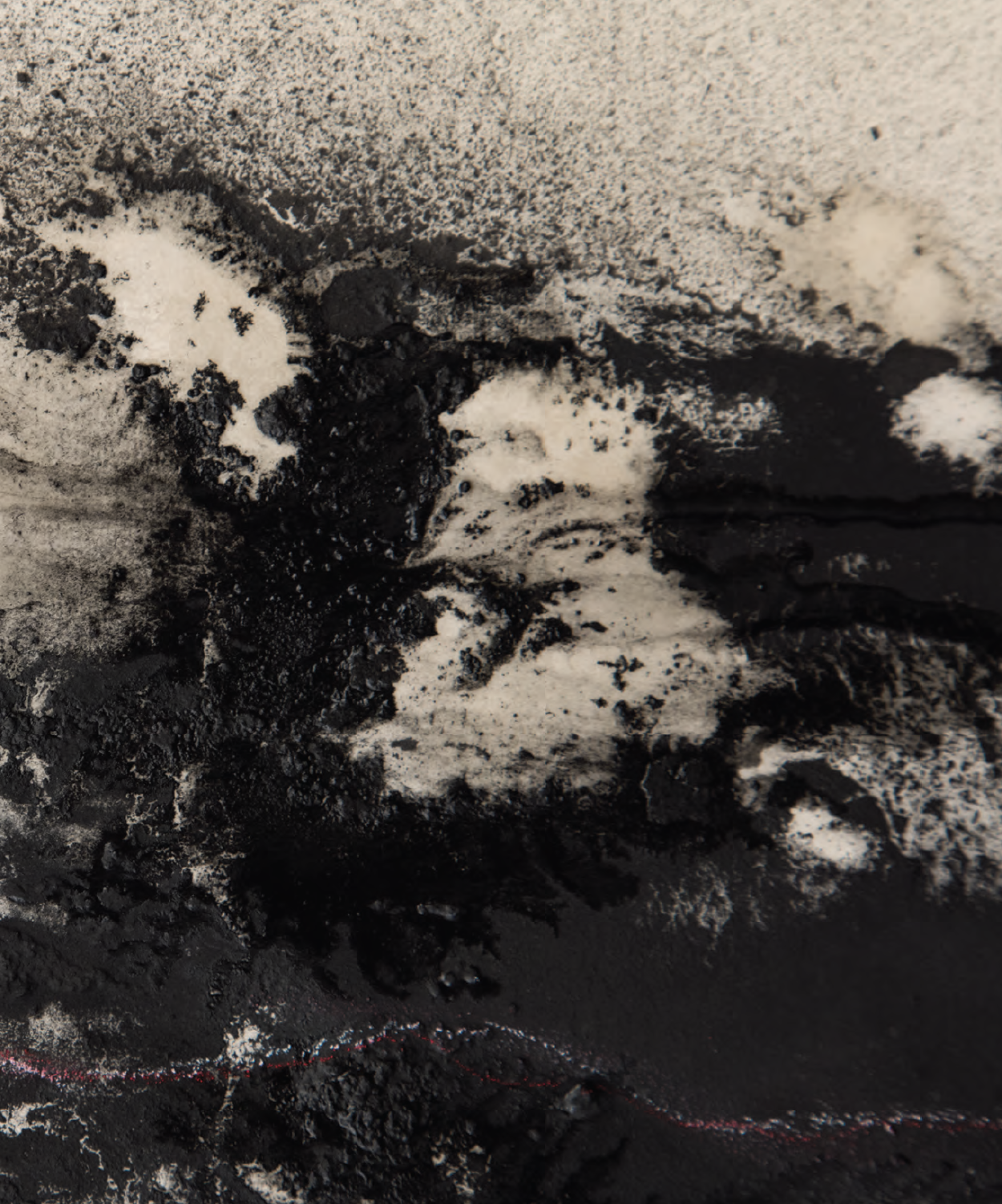

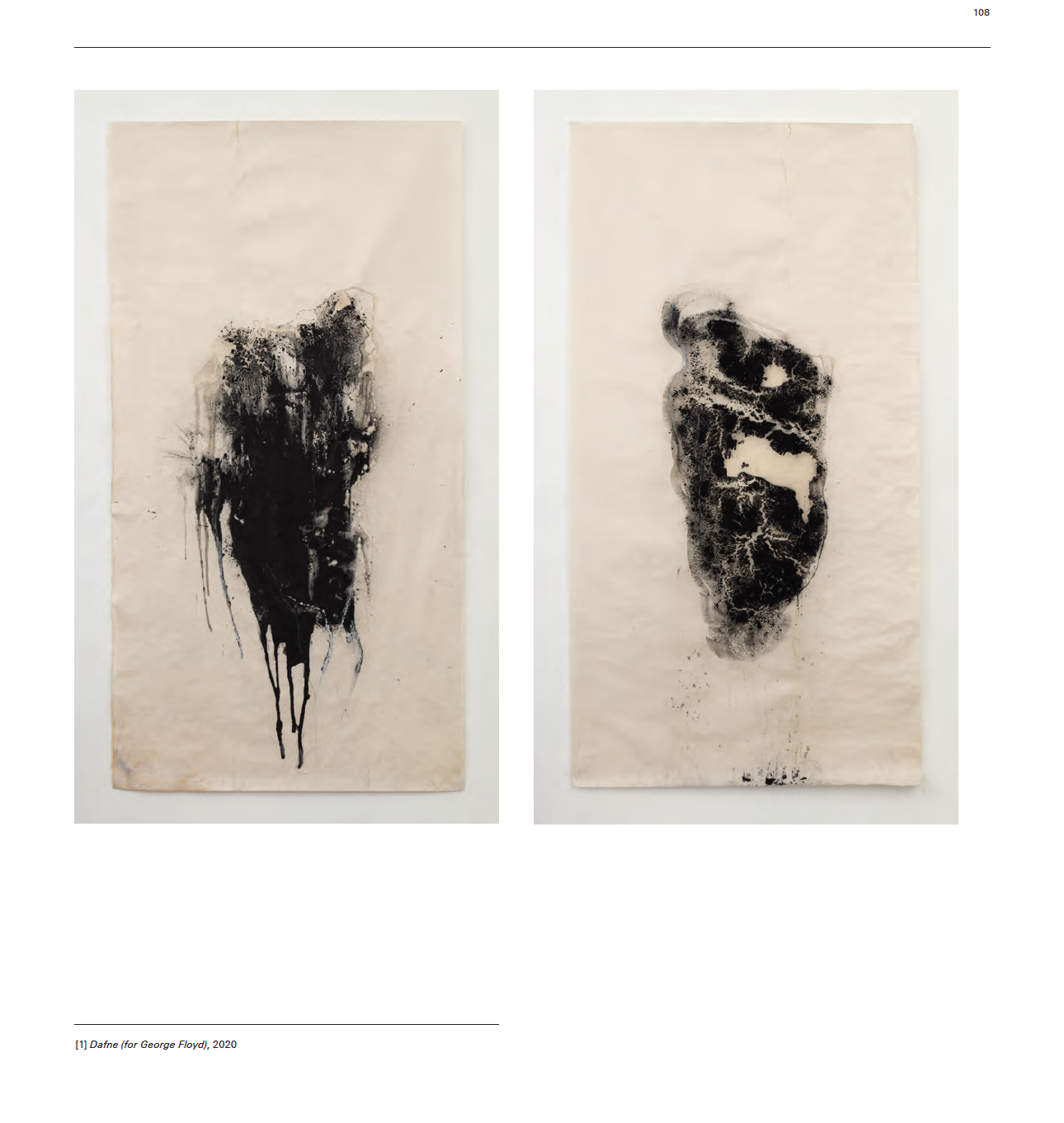

Weiss slowly approaches the work, until the camera is just a few inches from the bottom left of the image and then pans upward and across the surface to its right margins before panning downward again. The video ends at the drawing’s middle, a marshy terrain of accretions and stains made from the solution of water, resin, graphite powder, and traces of pencil and crayon. I have not been close up to every portion of Weiss’s composition. The video, less than a minute in duration, is more intended to introduce me to the chemistry of the work than make a story out of the track of its recording. There is a narrative here, though, that can be construed from the drawing’s dedication to the memory of George Floyd.

The suffocating knee of the Minneapolis police officer, who pinned the handcuffed victim to the street, ignoring his pleas until Floyd lost consciousness and then died, is nowhere visible in Weiss’s drawing. The unconscionable violence of Floyd’s killing, itself recorded on cellphones of passersby, brings witness to his audible cries—“I can’t breathe”—and the silent impassivity of the officer who, at several points, stares into the cameras recording the murder he is committing.

Weiss’s drawing is not an addition to the multiple representational depictions of Floyd dying or else pictured at moments in the life he led up until that street, that knee, that death. The title reference to Dafne also invokes a story of violence; not of merciless human indifference, but of a classical Greco-Roman narrative of the attempted rape of a naiad by a god. Apollo, infatuated with Daphne (the result of a curse put upon him by Cupid), pursues the frightened girl whose pleas for help are granted by her father, the river god Peneus, whose intervention at the penultimate moment is to transform her into a laurel tree. There is nobody intervening in the death of George Floyd, but those who recorded it have shared their witness with the world.

From the dedication tied to an individual artwork, through the titular invocation of a suite of works, to the ribbon of thematic links covering decades and the great range of Weiss’ material, projective, and sound production, she has made the elegiac terms of resistance the emotional core of her art. Weiss’ extensive previous series of drawings, video, and sound works, Two Laments (19 Cantos), 2015-2020, and her upcoming multilayered project, Nirbhaya, the anti-monument soon to be constructed in Weiss’ native Poland and in the U.S., also invoke predatory violence, in the notorious 2012 case of kidnapping, rape, and murder of a young woman in New Delhi, India. The Indian newspapers were not allowed to publish the victim’s name but she was identified as “Nirbhaya,” the Hindi word for “Fearless,” by the mass anti-violence-against-women movement her murder inspired.

For more than twenty years drawing as performance has been a component of installations and exhibitions of Weiss’ art. She directly connects her drawing to her work in projective and sound mediums, and even to her institutional and outdoor installation projects. As she explains this in a 2016 artist’s statement: “I work with traces, remnants, after-histories, post-memories, archives, fragments. Not being a proper witness nor a proper survivor, I invite others to inhabit my films, sound compositions and performances to join me in the space of lamentation, understood as a political gesture.” [i]

The mise-en-scène of Weiss’ projective works often includes layering of actions, places, sounds, and documents that generate moments of visual or aural ambiguity; fragments of duration as well as experience. In early public performances, Weiss drew on sheets of paper on the floor, with both eyes closed and with both hands, like a pianist absorbed in the feeling of a musical passage. In the silence of drawing or the keening of lamentation Weiss’ absorption in such moments is an invitation to empathy from those observing her creative work.

The drawing Weiss has shown me is visible in its entirety only for a few seconds of the cellphone video, but I have seen it subsequently in photographs of the Dafne drawings, documenting the works to be shown in Monika Weiss-Nirbhaya exhibition at the Centre for Polish Sculpture in Orońsko, Poland. Earlier I alluded to an ideal viewpoint for regarding the work. The catalogue photographs are not taken from that oblique angle. Rather, their frontality is for the purposes of being reproduced on pages, with critical and psychological angles of approach arising from the texts in which they are situated. The video is meant to engage me in something other about the drawing; the gestures and applications by which it was made.

The Dafne drawings, like so much of Weiss’ prior graphic output, are made on large-scale paper placed on the floor. Weiss pours her mediums onto Japanese Tokoatsu rice paper sheets, some of which have already been lightly drawn upon in pencil and/or crayon. The artist describes the resulting puddle as “paradoxically cold lava” [ii] because of the fissures and flaking that occur as the form congeals and dries. The forms are further manipulated by lifting corners, sides, or the entire sheet during the drying process.

The retrieval of intentionality from the phenomenal in the drawings is provided by the few, but deliberate, pencil or crayon lines, as well as the erasures and smearings by Weiss’s hands. Ultimately, the dried mediums can be seen to have similar contours to those of crouching figures, a pose repertoire close in kind to the actions of performers in Weiss’ large-scale projection videos. In the case of the informal video that inspires this writing, the fluid movement of the camera in Weiss’s hand glides over the drawing surface at a speed and distance that, I believe, is close to the pathways of inundation by which the composition being recorded came to exist.

There is another analogy here as well, to playing music. Weiss is a skilled pianist and the daughter of the late Polish pianist and music teacher Gabriela Weiss. The lessons in reading musical scores imparted to her in childhood by her mother were part of the training of ear, hand, and posture in order for the music to be made. In a recent correspondence Weiss has referenced her piano lessons thusly: “She taught me by pressing her fingers into my arm, to physically demonstrate how heavy each finger has to feel, how my entire body needs to rest in it, and thus each key of the piano becomes full of my entire body.” [iii] The physical force of striking each note is necessary for the transmogrifying response of the instrument—its music—to happen.

Weiss’ drawings are a duration of cumulative actions as well as remainders of their material and gestural effects. They have vestiges of the time spent in their making in common with music, and in Weiss’s new Dafne synthesizer compositions, based on recordings of her piano improvisations, the layering and shifts of pitch and tempo to be heard there are equivalent to the artist’s working and reworking the surfaces of her drawings. Weiss reminds us that Dafne is a fable of metamorphosis, “the strain of transformation, from a living body of a woman into a living body of a tree.” [iv]

Describing her musical composing methods, Weiss notes the time passing between recording and editing sessions as necessary pauses to make “a new sonic entity.”[v] This interval is an exquisite parallel to the time she spends waiting for the colloidal applications in her drawings to, as she describes it, “metamorphosize into their finished state.” [vi]

How, then, do we reconcile the succession of references to violence with the Dafne drawings and music? Weiss draws our attention to origins in both:

“In the drawing and sound process, the original event of pouring, outlining and improvising is important. Yet the transformation that takes place after the original event creates meaning different from the original act or gesture.”[vii]

The Dafne (for Nirbhaya) works are a response, as were the Nirbhaya works before them, to great and terrible human crimes, but they have never been intended just to be moral judgments. As the artist puts it in conversation. “I’m more interested in Daphne being rescued by nature.”[viii] This invocation of nature calls to mind a description of Weiss’ performance work by Krzysztof Wodiczko, “Not being a proper witness, not being a proper survivor, and not being able to recall the very overwhelming events, Monika Weiss, indirectly, on the basis of found fragments of images and encountered sites, chooses to inhabit them performatively through her art.” [ix]

Elaine Scarry has written about the inexpressibility of physical pain in her influential 1985 study, The Body in Pain, but Scarry’s interest expands from this to consider the social, political, and perceptual consequences of such pain. In so doing, she notes, “Physical pain does not simply resist language but actively destroys it, bringing about an immediate reversion to a state anterior to language, to the sounds and cries a human being makes before language is learned.” [x] In regarding the pain of others, Weiss has made stirring emotional use of lamentation, the wailing of those who would bring back the voices of the silenced.

Wodiczko’s “overwhelming” and Scarry’s “sounds and cries” are each attempts to characterize affect exceeding comprehension, and to make a report on such epistemological vastness by means of heartfelt but reductive language. Weiss shares their indignation, but her responsibilities to her art also exceed the forensic or the jurisdictional. Weiss employs metamorphoses, whether in material or sound, to move us from the unbearable weight of suffering towards the intersection of justice and jouissance. As Weiss concluded, in her memory of learning the piano, “Later I understood that for music to happen, every note must express the entire world.” [xi]

Buzz Spector, New York and St. Louis, 2020

Notes:

[i] Weiss, Monika. “Wrath (Canto 1, Canto 2, Canto 3), 2015,” artist’s statement for exhibition,

“Fireflies in the Night,” curated by Barbara London, Kalliopi Minioudaki, and Francesca Pietropaolo, Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center, Athens, Greece, June 23-26, 2016

[ii] Weiss, Monika. Conversation with the artist, July 16, 2020

[iii] Weiss, Monika. Email of June 9, 2020

[iv] Weiss, Monika. “Metamorphosis: Dafne [for Nirbhaya] series of drawings and sound works,” unpublished artist’s statement, 2020

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Weiss, Monika. Conversation with the artist, July 16, 2020

[vii] Weiss, Monika. “Metamorphosis: Dafne [for Nirbhaya] series of drawings and sound works”

[viii] Weiss, Monika. FaceTime conversation, June 29, 2020

[ix] Wodiczko, Krzysztof. Introduction to Monika Weiss performance at Harvard University, 2014, accessed on the artist’s website, July 11, 2020

[x] Scarry, Elaine. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World, New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985, p.4

[xi] Weiss. “Metamorphosis: Dafne [for Nirbhaya] series of drawings and sound works”

Buzz Spector is an artist and writer who recently moved to upstate New York. Drawing has been important to his studio practice from the beginning of his career. Spector describes the systematic page tearing in many of his works with paper as edges becoming lines. In addition to artmaking, Spector is a widely published critical writer whose essays and reviews have appeared in Afterimage, American Craft, Artforum, and Art on Paper, among many other magazines and journals. He is emeritus professor of art in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis.